19 sept 2012

Secret documents reveal US involvement in "Sabra and Shatila" massacres

Five secret documents dating back to 1982 revealed clear US involvement in the Sabra and Shatila massacres that took place in 1982 over a three-day period from September 16-18.

The documents include verbatim transcripts of meetings between US and Israeli officials before and during the three-day massacre led by the right-wing Lebanese Christian Phalange militia that left roughly 2,000 people dead, mostly children, women and elderly men, New York Times revealed on the 30th anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacres.

The documents revealed that the Israelis misled American diplomats about events in Beirut and bullied them into accepting the spurious claim that thousands of “terrorists” were in the camps,” Seth Onziska, a doctoral candidate in international history at Columbia University and who obtained the documents, reported.

“Most troubling, when the United States was in a position to exert strong diplomatic pressure on Israel that could have ended the atrocities, it failed to do so,” the newspaper added.

On 16 September 1982, the first day of the massacre, US envoy to the Middle East Morris Draper met with Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon who justified Israel's occupation of west Beirut by claiming that “2,000 to 3,000 terrorists” remained in that part of the city.

When Draper demanded that the Israeli forces immediately pull out of the area, Sharon responded with outrage: “I just don’t understand, what are you looking for? Do you want the terrorists to stay? Are you afraid that somebody will think that you were in collusion with us? Deny it. We denied it.”

According to the transcripts, Draper continued to insist that the Israelis leave, but eventually backed off once they agreed to a “gradual withdrawal” to allow for the Lebanese Army to enter the city. The Israelis insisted, however, that they wait 48 hours before allowing the plan to take effect.

Continuing his plea for some sign of an Israeli withdrawal, Draper warned that critics would say, “Sure, the I.D.F. is going to stay in West Beirut and they will let the Lebanese go and kill the Palestinians in the camps.” Sharon replied: “So, we’ll kill them. They will not be left there. You are not going to save them. You are not going to save these groups of the international terrorism.”

Draper's response was surprising when he said: “We are not interested in saving any of these people.”

Sharon declared: “If you don’t want the Lebanese to kill them, we will kill them.”

Draper then caught himself, and backtracked. He reminded the Israelis that the United States had painstakingly facilitated the P.L.O. exit from Beirut “so it wouldn’t be necessary for you to come in.” He added, “You should have stayed out.”

UK silent on Sabra Shatila massacre

Britain went out of its way earlier this month to condemn the 1972 killing of 11 Israeli athletes, but it has failed to even raise the horrific Sabra and Shatila massacre of more than 3,000 Palestinian and Lebanese civilians by Israeli-affiliated terrorists ten years later.

The Israeli regime unleashed Phalange terrorists on Muslim residents of Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in the Lebanese capital of Beirut between September 16 and 18, 1982.

The terrorists entered the refugee camps, supposedly guarded by Israeli regime’s forces, on September 16, while Israeli troops fired flares to help attackers in their butchery of innocent Muslims including scores of children, women and old men.

As many as 3,500 people were slaughtered with many women raped before being killed.

In December 1982, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the massacre in Resolution 37/123 with a massive 123 yes votes, without any opposition as an act of “genocide,” for which the Israeli regime was implicitly blamed.

However, Britain joined hands with its western allies the US, Germany, Canada and France to abstain on the resolution apparently because Tel Aviv was indirectly blamed, while later in February 1983 the Israeli regime found -- in what British journalist David Hirst called a flawed inquiry full of omissions of evidence to rid the regime of full responsibility for the massacre -- that its forces were “indirectly” responsible for the butchery.

British Foreign Secretary William Hague said on the 40th anniversary of the Munich attacks on Israeli team members on September 5 that he and his colleagues “reiterate our determination to confront terrorism and stand with the victims of terrorism wherever it may occur.”

Nonetheless, Britain seems not to include victims of Israeli state terrorism in its list of terror victims, nor consider Palestinian and Lebanese civilians massacred by the regime both in 1982 and later in the 2008 Gaza Massacre as worthy of a “sad” remembrance.

Declassified documents show American ‘outrage’ over U.S. marine shot at by Israeli colonel

The documents include verbatim transcripts of meetings between US and Israeli officials before and during the three-day massacre led by the right-wing Lebanese Christian Phalange militia that left roughly 2,000 people dead, mostly children, women and elderly men, New York Times revealed on the 30th anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacres.

The documents revealed that the Israelis misled American diplomats about events in Beirut and bullied them into accepting the spurious claim that thousands of “terrorists” were in the camps,” Seth Onziska, a doctoral candidate in international history at Columbia University and who obtained the documents, reported.

“Most troubling, when the United States was in a position to exert strong diplomatic pressure on Israel that could have ended the atrocities, it failed to do so,” the newspaper added.

On 16 September 1982, the first day of the massacre, US envoy to the Middle East Morris Draper met with Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon who justified Israel's occupation of west Beirut by claiming that “2,000 to 3,000 terrorists” remained in that part of the city.

When Draper demanded that the Israeli forces immediately pull out of the area, Sharon responded with outrage: “I just don’t understand, what are you looking for? Do you want the terrorists to stay? Are you afraid that somebody will think that you were in collusion with us? Deny it. We denied it.”

According to the transcripts, Draper continued to insist that the Israelis leave, but eventually backed off once they agreed to a “gradual withdrawal” to allow for the Lebanese Army to enter the city. The Israelis insisted, however, that they wait 48 hours before allowing the plan to take effect.

Continuing his plea for some sign of an Israeli withdrawal, Draper warned that critics would say, “Sure, the I.D.F. is going to stay in West Beirut and they will let the Lebanese go and kill the Palestinians in the camps.” Sharon replied: “So, we’ll kill them. They will not be left there. You are not going to save them. You are not going to save these groups of the international terrorism.”

Draper's response was surprising when he said: “We are not interested in saving any of these people.”

Sharon declared: “If you don’t want the Lebanese to kill them, we will kill them.”

Draper then caught himself, and backtracked. He reminded the Israelis that the United States had painstakingly facilitated the P.L.O. exit from Beirut “so it wouldn’t be necessary for you to come in.” He added, “You should have stayed out.”

UK silent on Sabra Shatila massacre

Britain went out of its way earlier this month to condemn the 1972 killing of 11 Israeli athletes, but it has failed to even raise the horrific Sabra and Shatila massacre of more than 3,000 Palestinian and Lebanese civilians by Israeli-affiliated terrorists ten years later.

The Israeli regime unleashed Phalange terrorists on Muslim residents of Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in the Lebanese capital of Beirut between September 16 and 18, 1982.

The terrorists entered the refugee camps, supposedly guarded by Israeli regime’s forces, on September 16, while Israeli troops fired flares to help attackers in their butchery of innocent Muslims including scores of children, women and old men.

As many as 3,500 people were slaughtered with many women raped before being killed.

In December 1982, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the massacre in Resolution 37/123 with a massive 123 yes votes, without any opposition as an act of “genocide,” for which the Israeli regime was implicitly blamed.

However, Britain joined hands with its western allies the US, Germany, Canada and France to abstain on the resolution apparently because Tel Aviv was indirectly blamed, while later in February 1983 the Israeli regime found -- in what British journalist David Hirst called a flawed inquiry full of omissions of evidence to rid the regime of full responsibility for the massacre -- that its forces were “indirectly” responsible for the butchery.

British Foreign Secretary William Hague said on the 40th anniversary of the Munich attacks on Israeli team members on September 5 that he and his colleagues “reiterate our determination to confront terrorism and stand with the victims of terrorism wherever it may occur.”

Nonetheless, Britain seems not to include victims of Israeli state terrorism in its list of terror victims, nor consider Palestinian and Lebanese civilians massacred by the regime both in 1982 and later in the 2008 Gaza Massacre as worthy of a “sad” remembrance.

Declassified documents show American ‘outrage’ over U.S. marine shot at by Israeli colonel

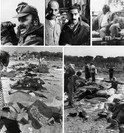

A Palestinian woman carries portraits of her relatives who were killed during the Sabra and Shatila massacre during a march to mark the 30th anniversary of the massacre in Beirut.

On Sunday, the 30th anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacre was commemorated by people of different nationalities around the world.

In Lebanon the commemoration was only observed by Palestinians living in refugee camps; Lebanese people were not concerned.

The massacre carried out by the Phalange, a Christian Maronite militia acting in full cooperation with Israel, was among the most atrocious episodes of recent history. But it is still absent from our collective Lebanese memory.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre is another taboo in Lebanon that needs to be addressed publicly and soberly; maybe admitting the wrongdoing could prevent us from further subjugating the Palestinian refugees who are residing here temporarily until they return to their occupied homeland.

The perpetrators of the massacre are still alive and could be found inside and outside Lebanon; so too are some of the witnesses who survived the massacre, and lost their loved ones. They are still awaiting justice.

On 16 September 1982, Jameela Khalifeh was a teenage girl. The three long days of slaughter still haunts her memories.

This week, Khalifeh welcomed us with a smile to her dim apartment on the busy Sabra strip. Outside, there was bustling life: people stopping and shopping at vegetable stalls and bootleg DVD stores.

“I was 16 and had just got engaged,” Kahlifeh said. “I was living at my parents’ home with three sisters and my brother.”

“We won’t forget” Holding out a photo, she added: “This is my father Mohammad Khalifeh, this picture was taken after they shot him in the head and dumped his body on the side of the street.” On the back of the picture, there is a certificate issued by the Palestine Liberation Organization. It contains Mohammad’s name and the words “So we won’t forget.”

“On 16 September, during the invasion, Israeli soldiers descended onto the camp from the Sports City stadium located on a hilltop overlooking the camp. We knew that the Israelis were stationed in the stadium and they [the Israelis] knew that the fedayeen [PLO fighters] had evacuated the camp, therefore we assured each other they wouldn’t kill us unarmed families.

“Next to the Israeli soldiers there were the Phalange militants who spoke in a Lebanese dialect; each militant dressed in a cowboy hat and a white armband with a green cedar on it [the logo of the Phalangists’ political party]. I remember the Israelis were speaking broken Arabic to the Lebanese militants but mostly they spoke in Hebrew. My mother understood Hebrew from the time she used to live in Palestine before 1948.

“While we were fleeing, we got stopped by a Phalange militant who pointed his rifle to my mother’s belly, but the Israeli soldier told the Lebanese militant, ‘Don’t kill the Madam and the babies; we are here to kill men only.’ We came out to the streets; my father was with us in the shelter beneath the building, and the Israelis — with the Phalangists — started to call us through microphones urging us to come out from the shelters, announcing: ‘If you surrender you will be safe.’

“Overwhelming stench” “We came out from the shelter to the street; I remember the stench was overwhelming, and I was waving a white piece of cloth. My father finally decided to come out with us from the shelter. I made sure to stay by his side; I was truly attached to my father, holding his hand tight.

“The moment we emerged we were taken by Israeli soldiers and Lebanese militants. At this point my father became nervous. He looked at me and whispered, ‘I’m going home.’ The moment we joined families from the camp led by the militants, my father panicked, let go of my hand and ran home. When he got home he found militants inside the building, searching it, so he immediately ran back to us.

“While he was running towards us: they shot him in the head. My mother saw him getting shot, I didn’t.

“While we were being led at gunpoint, we found a small alley that led to the camp so we split off from the marching, cattled crowds and made it back to the main mosque in the camp. The mosque was full of people from Shatila. On arrival, we told them that they [the Phalange] are killing and slaughtering families but the elders of the camp said we were lying; that there was nothing, that we should calm down. Upon our insistence the elders decided to go see what was going on. The elder men never came back to the mosque. After waiting in the mosque for few hours with no news about the elders we and other families went to Gaza hospital at the the entrance to Sabra.

“We used to live in the street of Hay al-Gharbi next to the Doukhi grocery store. In our neighborhood only my family and our neighbor survived the killing, the rest were all killed. I remember seven or eight corpses on top of each other, in the street below our building; we had to step over them.

“The Israelis and Phalangists led us in a march, to finish us, to kill us like they did to the others. Luckily, we managed to escape through the alley. The Israelis were dressed in full military uniform with iron helmets. The Lebanese militants were dressed in cowboy hats, blue jeans and daggers hanging from their belts. Some among them wore black ski masks. All carried Kalashnikovs.

Putting Sharon in the dock “A few years ago 300 of us hired the lawyer Shibli Mallat to sue Ariel Sharon [Israel’s defense minister in 1982, and later, prime minister] for the massacre and we wanted to take him to a tribunal in Belgium. We saw pictures of Sharon standing at the sports stadium next to Israeli tanks overlooking the camp, and we know he was watching the massacre and the killing of Palestinians. I still want Sharon to be put on trial even if he, ironically, has been in a coma for years and clinically dead.

“Thirty years after the massacre, take a look at how we live. We are seven people staying in two small rooms. Our life has been deteriorating for the last 30 years; we still can’t work and can’t move outside the camp to a decent place. We buy drinking and washing water on a daily basis. We buy electricity from a generator; the Lebanese government only gives us two hours of power a day. My two sons work at an aluminum factory. Because they are Palestinian they get paid less than their coworkers. And my 23-year-old daughter works at a café.

“My daughter went to get a loan from a bank like her coworkers did but when she got to the bank and showed her papers they told her, ‘Sorry, you can’t get a loan because you are Palestinian.’ Being a Palestinian in Lebanon is a daily, ongoing struggle for survival. That’s why each time a woman gives birth we make sure the newborn is brought up to believe in the right of return to Palestine and we emphasize that we are only guests here.

“We want to return to Palestine but until then I want to leave this country and go anywhere we’ll be treated as human beings. We never gave up, Palestine is ours, and we are going to return, but we are tired of not being able to live an honorable, decent life.

“We are from Jaffa. My mother never stops talking about the time she lived in Jaffa, and the way Israelis started coming as refugees, at first sheltering in houses, then starting to push Palestinians out of their houses.”

Atrocity ignored On 16 September this year, Pope Benedict XVI visited Beirut, where he urged the Lebanese — both Christians and Muslims — to coexist in peace. The pope preached on various issues concerning the region but failed to mention the Sabra and Shatila massacre and the plight of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Many were furious with his omission of any reference to the massacre in his public address on Beirut’s waterfront. As he was speaking on the anniversary of the massacre, the omission was all the more hurtful.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre is one of many atrocities that occurred during the long years of the Lebanese civil war. Ironically, political leaders, who were then warlords, were sitting on the frontline on Sunday during the Pope’s sermon; among those leaders were members of the Phalangist party, who are believed to be responsible for the massacre in Sabra and Shatila.

There will come a day when Lebanon will break the taboo of the Sabra and Shatila massacre and justice will be served to the families of the thousands killed 30 years ago. But until that day comes, Palestinian refugees will still be marginalized, living in inhumane conditions inside overcrowded camps.

Moe Ali Nayel is a journalist and fixer based in Beirut.

On Sunday, the 30th anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacre was commemorated by people of different nationalities around the world.

In Lebanon the commemoration was only observed by Palestinians living in refugee camps; Lebanese people were not concerned.

The massacre carried out by the Phalange, a Christian Maronite militia acting in full cooperation with Israel, was among the most atrocious episodes of recent history. But it is still absent from our collective Lebanese memory.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre is another taboo in Lebanon that needs to be addressed publicly and soberly; maybe admitting the wrongdoing could prevent us from further subjugating the Palestinian refugees who are residing here temporarily until they return to their occupied homeland.

The perpetrators of the massacre are still alive and could be found inside and outside Lebanon; so too are some of the witnesses who survived the massacre, and lost their loved ones. They are still awaiting justice.

On 16 September 1982, Jameela Khalifeh was a teenage girl. The three long days of slaughter still haunts her memories.

This week, Khalifeh welcomed us with a smile to her dim apartment on the busy Sabra strip. Outside, there was bustling life: people stopping and shopping at vegetable stalls and bootleg DVD stores.

“I was 16 and had just got engaged,” Kahlifeh said. “I was living at my parents’ home with three sisters and my brother.”

“We won’t forget” Holding out a photo, she added: “This is my father Mohammad Khalifeh, this picture was taken after they shot him in the head and dumped his body on the side of the street.” On the back of the picture, there is a certificate issued by the Palestine Liberation Organization. It contains Mohammad’s name and the words “So we won’t forget.”

“On 16 September, during the invasion, Israeli soldiers descended onto the camp from the Sports City stadium located on a hilltop overlooking the camp. We knew that the Israelis were stationed in the stadium and they [the Israelis] knew that the fedayeen [PLO fighters] had evacuated the camp, therefore we assured each other they wouldn’t kill us unarmed families.

“Next to the Israeli soldiers there were the Phalange militants who spoke in a Lebanese dialect; each militant dressed in a cowboy hat and a white armband with a green cedar on it [the logo of the Phalangists’ political party]. I remember the Israelis were speaking broken Arabic to the Lebanese militants but mostly they spoke in Hebrew. My mother understood Hebrew from the time she used to live in Palestine before 1948.

“While we were fleeing, we got stopped by a Phalange militant who pointed his rifle to my mother’s belly, but the Israeli soldier told the Lebanese militant, ‘Don’t kill the Madam and the babies; we are here to kill men only.’ We came out to the streets; my father was with us in the shelter beneath the building, and the Israelis — with the Phalangists — started to call us through microphones urging us to come out from the shelters, announcing: ‘If you surrender you will be safe.’

“Overwhelming stench” “We came out from the shelter to the street; I remember the stench was overwhelming, and I was waving a white piece of cloth. My father finally decided to come out with us from the shelter. I made sure to stay by his side; I was truly attached to my father, holding his hand tight.

“The moment we emerged we were taken by Israeli soldiers and Lebanese militants. At this point my father became nervous. He looked at me and whispered, ‘I’m going home.’ The moment we joined families from the camp led by the militants, my father panicked, let go of my hand and ran home. When he got home he found militants inside the building, searching it, so he immediately ran back to us.

“While he was running towards us: they shot him in the head. My mother saw him getting shot, I didn’t.

“While we were being led at gunpoint, we found a small alley that led to the camp so we split off from the marching, cattled crowds and made it back to the main mosque in the camp. The mosque was full of people from Shatila. On arrival, we told them that they [the Phalange] are killing and slaughtering families but the elders of the camp said we were lying; that there was nothing, that we should calm down. Upon our insistence the elders decided to go see what was going on. The elder men never came back to the mosque. After waiting in the mosque for few hours with no news about the elders we and other families went to Gaza hospital at the the entrance to Sabra.

“We used to live in the street of Hay al-Gharbi next to the Doukhi grocery store. In our neighborhood only my family and our neighbor survived the killing, the rest were all killed. I remember seven or eight corpses on top of each other, in the street below our building; we had to step over them.

“The Israelis and Phalangists led us in a march, to finish us, to kill us like they did to the others. Luckily, we managed to escape through the alley. The Israelis were dressed in full military uniform with iron helmets. The Lebanese militants were dressed in cowboy hats, blue jeans and daggers hanging from their belts. Some among them wore black ski masks. All carried Kalashnikovs.

Putting Sharon in the dock “A few years ago 300 of us hired the lawyer Shibli Mallat to sue Ariel Sharon [Israel’s defense minister in 1982, and later, prime minister] for the massacre and we wanted to take him to a tribunal in Belgium. We saw pictures of Sharon standing at the sports stadium next to Israeli tanks overlooking the camp, and we know he was watching the massacre and the killing of Palestinians. I still want Sharon to be put on trial even if he, ironically, has been in a coma for years and clinically dead.

“Thirty years after the massacre, take a look at how we live. We are seven people staying in two small rooms. Our life has been deteriorating for the last 30 years; we still can’t work and can’t move outside the camp to a decent place. We buy drinking and washing water on a daily basis. We buy electricity from a generator; the Lebanese government only gives us two hours of power a day. My two sons work at an aluminum factory. Because they are Palestinian they get paid less than their coworkers. And my 23-year-old daughter works at a café.

“My daughter went to get a loan from a bank like her coworkers did but when she got to the bank and showed her papers they told her, ‘Sorry, you can’t get a loan because you are Palestinian.’ Being a Palestinian in Lebanon is a daily, ongoing struggle for survival. That’s why each time a woman gives birth we make sure the newborn is brought up to believe in the right of return to Palestine and we emphasize that we are only guests here.

“We want to return to Palestine but until then I want to leave this country and go anywhere we’ll be treated as human beings. We never gave up, Palestine is ours, and we are going to return, but we are tired of not being able to live an honorable, decent life.

“We are from Jaffa. My mother never stops talking about the time she lived in Jaffa, and the way Israelis started coming as refugees, at first sheltering in houses, then starting to push Palestinians out of their houses.”

Atrocity ignored On 16 September this year, Pope Benedict XVI visited Beirut, where he urged the Lebanese — both Christians and Muslims — to coexist in peace. The pope preached on various issues concerning the region but failed to mention the Sabra and Shatila massacre and the plight of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Many were furious with his omission of any reference to the massacre in his public address on Beirut’s waterfront. As he was speaking on the anniversary of the massacre, the omission was all the more hurtful.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre is one of many atrocities that occurred during the long years of the Lebanese civil war. Ironically, political leaders, who were then warlords, were sitting on the frontline on Sunday during the Pope’s sermon; among those leaders were members of the Phalangist party, who are believed to be responsible for the massacre in Sabra and Shatila.

There will come a day when Lebanon will break the taboo of the Sabra and Shatila massacre and justice will be served to the families of the thousands killed 30 years ago. But until that day comes, Palestinian refugees will still be marginalized, living in inhumane conditions inside overcrowded camps.

Moe Ali Nayel is a journalist and fixer based in Beirut.

17 sept 2012

|

|

Yesterday marked 30 years since Christian Lebanese militiamen allied to Israel entered the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila and the adjacent neighborhood of Sabra in Beirut under the watch of the Israeli army and began a slaughter that caused outrage around the world. Over the next day and a half, up to 3500 Palestinian and Lebanese civilians, mostly women, children, and the elderly, were murdered in one of the worst atrocities in modern Middle Eastern history.

On this 30th anniversary, the New York Times has published an op-ed containing new details of discussions held between Israeli and American officials before and during the massacre. They reveal how Israeli officials, led by then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, misled and bullied American diplomats, rebuffing their concerns about the safety of the inhabitants of Sabra and Shatila. |

For journalists following this story, the IMEU offers the following fact sheet on the Sabra and Shatila massacre.

The Sabra & Shatila Massacre: 30 Years Later

- Lead Up -

- The Massacre -

- Casualty Figures -

- Aftermath -

Israel

The United States

The Palestinians

The Sabra & Shatila Massacre: 30 Years Later

- Lead Up -

- On June 6, 1982, Israel launched a massive invasion of Lebanon. It had been long planned by Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, who wanted to destroy or severely diminish the Palestine Liberation Organization, which was based in Lebanon at the time. Sharon also planned to install a puppet government headed by Israel's right-wing Lebanese Christian Maronite allies, the Phalangist Party.

- Israeli forces advanced all the way to the capital of Beirut, besieging and bombarding the western part of city, where the PLO was headquartered and the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila and the adjacent neighborhood of Sabra are located.

- Israel's bloody weeklong assault on West Beirut in August prompted harsh international criticism, including from the administration of US President Ronald Reagan, who many accused of giving a "green light" to Israel to launch the invasion. Under a US-brokered ceasefire agreement, PLO leaders and more than 14,000 fighters were to be evacuated from the country, with the US providing written assurances for the safety of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian civilians left behind. US Marines were deployed as part of a multinational force to oversee and provide security for the evacuation.

- On August 30, PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat left Beirut along with the remainder of the Palestinian fighters based in the city.

- On September 10, the Marines left Beirut. Four days later, on September 14, the leader of Israel's Phalangist allies, Bashir Gemayel, was assassinated. Gemayel had just been elected president of Lebanon by the Lebanese parliament, under the supervision of the occupying Israeli army. His death was a severe blow to Israel's designs for the country. The following day, Israeli forces violated the ceasefire agreement, moving into and occupying West Beirut.

- The Massacre -

- On Wednesday, September 15, the Israeli army surrounded the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila and the adjacent neighborhood of Sabra in West Beirut. The next day, September 16, Israeli soldiers allowed about 150 Phalangist militiamen into Sabra and Shatila.

- The Phalange, known for their brutality and a history of atrocities against Palestinian civilians, were bitter enemies of the PLO and its leftist and Muslim Lebanese allies during the preceding years of Lebanon's civil war. The enraged Phalangist militiamen believed, erroneously, that Phalange leader Gemayel had been assassinated by Palestinians. He was actually killed by a Syrian agent.

- Over the next day and a half, the Phalangists committed unspeakable atrocities, raping, mutilating, and murdering as many as 3500 Palestinian and Lebanese civilians, most of them women, children, and the elderly. Sharon would later claim that he could have had no way of knowing that the Phalange would harm civilians, however when US diplomats demanded to know why Israel had broken the ceasefire and entered West Beirut, Israeli army Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan justified the move saying it was "to prevent a Phalangist frenzy of revenge." On September 15, the day before the massacre began, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin told US envoy Morris Draper that the Israelis had to occupy West Beirut, "Otherwise, there could be pogroms."

- Almost immediately after the killing started, Israeli soldiers surrounding Sabra and Shatila became aware that civilians were being murdered, but did nothing to stop it. Instead, Israeli forces fired flares into the night sky to illuminate the darkness for the Phalangists, allowed reinforcements to enter the area on the second day of the massacre, and provided bulldozers that were used to dispose of the bodies of many of the victims.

- On the second day, Friday, September 17, an Israeli journalist in Lebanon called Defense Minister Sharon to inform him of reports that a massacre was taking place in Sabra and Shatila. The journalist, Ron Ben-Yishai, later recalled:

'I found [Sharon] at home sleeping. He woke up and I told him "Listen, there are stories about killings and massacres in the camps. A lot of our officers know about it and tell me about it, and if they know it, the whole world will know about it. You can still stop it." I didn't know that the massacre actually started 24 hours earlier. I thought it started only then and I said to him "Look, we still have time to stop it. Do something about it." He didn't react."' - On Friday afternoon, almost 24 hours after the killing began, Eitan met with Phalangist representatives. According to notes taken by an Israeli intelligence officer present: "[Eitan] expressed his positive impression received from the statement by the Phalangist forces and their behavior in the field," telling them to continue "mopping up the empty camps south of Fakahani until tomorrow at 5:00 a.m., at which time they must stop their action due to American pressure."

- On Saturday, American Envoy Morris Draper, sent a furious message to Sharon stating:

'You must stop the massacres. They are obscene. I have an officer in the camp counting the bodies. You ought to be ashamed. The situation is rotten and terrible. They are killing children. You are in absolute control of the area, and therefore responsible for the area.' - The Phalangists finally left the area at around 8 o'clock Saturday morning, taking many of the surviving men with them for interrogation at a soccer stadium. The interrogations were carried out with Israeli intelligence agents, who handed many of the captives back to the Phalange. Some of the men returned to the Phalange were later found executed.

- About an hour after the Phalangists departed Sabra and Shatila, the first journalists arrived on the scene and the first reports of what transpired began to reach the outside world.

- Casualty Figures -

- Thirty years later, there is still no accurate total for the number of people killed in the massacre. Many of the victims were buried in mass graves by the Phalange and there has been no political will on the part of Lebanese authorities to investigate.

- An official Israeli investigation, the Kahan Commission, concluded that between 700 and 800 people were killed, based on the assessment of Israeli military intelligence.

- An investigation by Beirut-based British journalist Robert Fisk, who was one of the first people on the scene after the massacre ended, concluded that 1700 people died.

- The Palestinian Red Crescent put the number of dead at more than 2000.

- In his book, Sabra & Shatila: Inquiry into a Massacre, Israeli journalist Amnon Kapeliouk reached a maximum figure of 3000 to 3500.

- Aftermath -

Israel

- Following international outrage, the Israeli government established a committee of inquiry, the Kahan Commission. Its investigation found that Defense Minister Sharon bore "personal responsibility" for the massacre, and recommended that he be removed from office. Although Prime Minister Begin removed him from his post as defense minister, Sharon remained in cabinet as a minister without portfolio. He would go on to hold numerous other cabinet positions in subsequent Israeli governments, including foreign minister during Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's first term in office. Nearly 20 years later, in March 2001, Sharon was elected prime minister of Israel.

- In June 2001, lawyers for 23 survivors of the massacre initiated legal proceedings against Sharon in a Belgian court, under a law allowing people to be prosecuted for war crimes committed anywhere in the world.

- In January 2002, Phalangist leader and chief liaison to Israel during the 1982 invasion, Elie Hobeika, was killed by a car bomb in Beirut. Hobeika led the Phalangist militiamen responsible for the massacre, and had announced that he was prepared to testify against Sharon, who was then prime minister of Israel, at a possible war crimes trial in Belgium. Hobeika's killers were never found.

- In June 2002, a panel of Belgian judges dismissed war crimes charges against Sharon because he wasn't present in the country to stand trial.

- In January 2006, Sharon suffered a massive stroke. He remains in a coma on life support.

The United States

- For the United States, which had guaranteed the safety of civilians left behind after the PLO departed, the massacre was a deep embarrassment, causing immense damage to its reputation in the region. The fact that US Secretary of State Alexander Haig was believed by many to have given Israel a "green light" to invade Lebanon compounded the damage.

- In the wake of the massacre, President Reagan sent the Marines back to Lebanon. Just over a year later, 241 American servicemen would be killed when two massive truck bombs destroyed their barracks in Beirut, leading Reagan to withdraw US forces for good.

The Palestinians

- For Palestinians, the Sabra and Shatila massacre was and remains a traumatic event, commemorated annually. Many survivors continue to live in Sabra and Shatila, struggling to eke out a living and haunted by their memories of the slaughter. To this day, no one has faced justice for the crimes that took place.

- For Palestinians, the Sabra and Shatila massacre serves as a powerful and tragic reminder of the vulnerable situation of millions of stateless Palestinians, and the dangers that they continue to face across the region, and around the world.

16 sept 2012

Declassified Documents Shed Light on a 1982 Massacre

Thirty years ago, a massacre occurred in Beirut’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.

The following declassified documents reveal conversations between high-level American and Israeli officials before, during and after the event. These English-language documents were released by the Israel State Archives in Jerusalem earlier this year.

Sept. 16, 1982. This document contains the talking points and minutes of a conversation between the American under secretary of state, Lawrence Eagleburger, and the Israeli ambassador to the United States, Moshe Arens. There was a heated discussion about the Israeli occupation of West Beirut. The cover note (in Hebrew) was written by a young Benjamin Netanyahu, who was then Israel's deputy chief of mission in Washington and was present at the meeting. p. 1

Sept. 17, 1982. This document is a verbatim transcript of a meeting that took place while the massacre was in progress. Those in attendance included America's Middle East envoy, Morris Draper; Israel's defense minister, Ariel Sharon; Israel's foreign minister, Yitzhak Shamir; and several other important Israeli officials. Key passages can be found on pages 37-41 in this document viewer. p. 11

Sept. 18, 1982. This document chronicles a conversation between the American secretary of state, George P. Shultz, and the Israeli ambassador, Moshe Arens. This discussion took place on the day American officials discovered that a massacre had taken place. p. 45

A Preventable Massacre

ON the night of Sept. 16, 1982, the Israeli military allowed a right-wing Lebanese militia to enter two Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut. In the ensuing three-day rampage, the militia, linked to the Maronite Christian Phalange Party, raped, killed and dismembered at least 800 civilians, while Israeli flares illuminated the camps’ narrow and darkened alleyways. Nearly all of the dead were women, children and elderly men.

Thirty years later, the massacre at the Sabra and Shatila camps is remembered as a notorious chapter in modern Middle Eastern history, clouding the tortured relationships among Israel, the United States, Lebanon and the Palestinians. In 1983, an Israeli investigative commission concluded that Israeli leaders were “indirectly responsible” for the killings and that Ariel Sharon, then the defense minister and later prime minister, bore “personal responsibility” for failing to prevent them.

While Israel’s role in the massacre has been closely examined, America’s actions have never been fully understood. This summer, at the Israel State Archives, I found recently declassified documents that chronicle key conversations between American and Israeli officials before and during the 1982 massacre. The verbatim transcripts reveal that the Israelis misled American diplomats about events in Beirut and bullied them into accepting the spurious claim that thousands of “terrorists” were in the camps. Most troubling, when the United States was in a position to exert strong diplomatic pressure on Israel that could have ended the atrocities, it failed to do so. As a result, Phalange militiamen were able to murder Palestinian civilians, whom America had pledged to protect just weeks earlier.

Israel’s involvement in the Lebanese civil war began in June 1982, when it invaded its northern neighbor. Its goal was to root out the Palestine Liberation Organization, which had set up a state within a state, and to transform Lebanon into a Christian-ruled ally. The Israel Defense Forces soon besieged P.L.O.-controlled areas in the western part of Beirut. Intense Israeli bombardments led to heavy civilian casualties and tested even President Ronald Reagan, who initially backed Israel. In mid-August, as America was negotiating the P.L.O.’s withdrawal from Lebanon, Reagan told Prime Minister Menachem Begin that the bombings “had to stop or our entire future relationship was endangered,” Reagan wrote in his diaries.

The United States agreed to deploy Marines to Lebanon as part of a multinational force to supervise the P.L.O.’s departure, and by Sept. 1, thousands of its fighters — including Yasir Arafat — had left Beirut for various Arab countries. After America negotiated a cease-fire that included written guarantees to protect the Palestinian civilians remaining in the camps from vengeful Lebanese Christians, the Marines departed Beirut, on Sept. 10.

Israel hoped that Lebanon’s newly elected president, Bashir Gemayel, a Maronite, would support an Israeli-Christian alliance. But on Sept. 14, Gemayel was assassinated. Israel reacted by violating the cease-fire agreement. It quickly occupied West Beirut — ostensibly to prevent militia attacks against the Palestinian civilians. “The main order of the day is to keep the peace,” Begin told the American envoy to the Middle East, Morris Draper, on Sept. 15. “Otherwise, there could be pogroms.”

By Sept. 16, the I.D.F. was fully in control of West Beirut, including Sabra and Shatila. In Washington that same day, Under Secretary of State Lawrence S. Eagleburger told the Israeli ambassador, Moshe Arens, that “Israel’s credibility has been severely damaged” and that “we appear to some to be the victim of deliberate deception by Israel.” He demanded that Israel withdraw from West Beirut immediately.

In Tel Aviv, Mr. Draper and the American ambassador, Samuel W. Lewis, met with top Israeli officials. Contrary to Prime Minister Begin’s earlier assurances, Defense Minister Sharon said the occupation of West Beirut was justified because there were “2,000 to 3,000 terrorists who remained there.” Mr. Draper disputed this claim; having coordinated the August evacuation, he knew the number was minuscule. Mr. Draper said he was horrified to hear that Mr. Sharon was considering allowing the Phalange militia into West Beirut. Even the I.D.F. chief of staff, Rafael Eitan, acknowledged to the Americans that he feared “a relentless slaughter.”

On the evening of Sept. 16, the Israeli cabinet met and was informed that Phalange fighters were entering the Palestinian camps. Deputy Prime Minister David Levy worried aloud: “I know what the meaning of revenge is for them, what kind of slaughter. Then no one will believe we went in to create order there, and we will bear the blame.” That evening, word of civilian deaths began to filter out to Israeli military officials, politicians and journalists.

At 12:30 p.m. on Sept. 17, Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir hosted a meeting with Mr. Draper, Mr. Sharon and several Israeli intelligence chiefs. Mr. Shamir, having reportedly heard of a “slaughter” in the camps that morning, did not mention it.

The transcript of the Sept. 17 meeting reveals that the Americans were browbeaten by Mr. Sharon’s false insistence that “terrorists” needed “mopping up.” It also shows how Israel’s refusal to relinquish areas under its control, and its delays in coordinating with the Lebanese National Army, which the Americans wanted to step in, prolonged the slaughter.

Mr. Draper opened the meeting by demanding that the I.D.F. pull back right away. Mr. Sharon exploded, “I just don’t understand, what are you looking for? Do you want the terrorists to stay? Are you afraid that somebody will think that you were in collusion with us? Deny it. We denied it.” Mr. Draper, unmoved, kept pushing for definitive signs of a withdrawal. Mr. Sharon, who knew Phalange forces had already entered the camps, cynically told him, “Nothing will happen. Maybe some more terrorists will be killed. That will be to the benefit of all of us.” Mr. Shamir and Mr. Sharon finally agreed to gradually withdraw once the Lebanese Army started entering the city — but they insisted on waiting 48 hours (until the end of Rosh Hashana, which started that evening).

Continuing his plea for some sign of an Israeli withdrawal, Mr. Draper warned that critics would say, “Sure, the I.D.F. is going to stay in West Beirut and they will let the Lebanese go and kill the Palestinians in the camps.”

Mr. Sharon replied: “So, we’ll kill them. They will not be left there. You are not going to save them. You are not going to save these groups of the international terrorism.”

Mr. Draper responded: “We are not interested in saving any of these people.” Mr. Sharon declared: “If you don’t want the Lebanese to kill them, we will kill them.”

Mr. Draper then caught himself, and backtracked. He reminded the Israelis that the United States had painstakingly facilitated the P.L.O. exit from Beirut “so it wouldn’t be necessary for you to come in.” He added, “You should have stayed out.”

Mr. Sharon exploded again: “When it comes to our security, we have never asked. We will never ask. When it comes to existence and security, it is our own responsibility and we will never give it to anybody to decide for us.” The meeting ended with an agreement to coordinate withdrawal plans after Rosh Hashana.

By allowing the argument to proceed on Mr. Sharon’s terms, Mr. Draper effectively gave Israel cover to let the Phalange fighters remain in the camps. Fuller details of the massacre began to emerge on Sept. 18, when a young American diplomat, Ryan C. Crocker, visited the gruesome scene and reported back to Washington.

Years later, Mr. Draper called the massacre “obscene.” And in an oral history recorded a few years before his death in 2005, he remembered telling Mr. Sharon: “You should be ashamed. The situation is absolutely appalling. They’re killing children! You have the field completely under your control and are therefore responsible for that area.”

On Sept. 18, Reagan pronounced his “outrage and revulsion over the murders.” He said the United States had opposed Israel’s invasion of Beirut, both because “we believed it wrong in principle and for fear that it would provoke further fighting.” Secretary of State George P. Shultz later admitted that “we are partially responsible” because “we took the Israelis and the Lebanese at their word.” He summoned Ambassador Arens. “When you take military control over a city, you’re responsible for what happens,” he told him. “Now we have a massacre.”

But the belated expression of shock and dismay belies the Americans’ failed diplomatic effort during the massacre. The transcript of Mr. Draper’s meeting with the Israelis demonstrates how the United States was unwittingly complicit in the tragedy of Sabra and Shatila.

Ambassador Lewis, now retired, told me that the massacre would have been hard to prevent “unless Reagan had picked up the phone and called Begin and read him the riot act even more clearly than he already did in August — that might have stopped it temporarily.” But “Sharon would have found some other way” for the militiamen to take action, Mr. Lewis added.

Nicholas A. Veliotes, then the assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, agreed. “Vintage Sharon,” he said, after I read the transcript to him. “It is his way or the highway.”

The Sabra and Shatila massacre severely undercut America’s influence in the Middle East, and its moral authority plummeted. In the aftermath of the massacre, the United States felt compelled by “guilt” to redeploy the Marines, who ended up without a clear mission, in the midst of a brutal civil war.

On Oct. 23, 1983, the Marine barracks in Beirut were bombed and 241 Marines were killed. The attack led to open warfare with Syrian-backed forces and, soon after, the rapid withdrawal of the Marines to their ships. As Mr. Lewis told me, America left Lebanon “with our tail between our legs.”

The archival record reveals the magnitude of a deception that undermined American efforts to avoid bloodshed. Working with only partial knowledge of the reality on the ground, the United States feebly yielded to false arguments and stalling tactics that allowed a massacre in progress to proceed.

The lesson of the Sabra and Shatila tragedy is clear. Sometimes close allies act contrary to American interests and values. Failing to exert American power to uphold those interests and values can have disastrous consequences: for our allies, for our moral standing and most important, for the innocent people who pay the highest price of all.

The following declassified documents reveal conversations between high-level American and Israeli officials before, during and after the event. These English-language documents were released by the Israel State Archives in Jerusalem earlier this year.

Sept. 16, 1982. This document contains the talking points and minutes of a conversation between the American under secretary of state, Lawrence Eagleburger, and the Israeli ambassador to the United States, Moshe Arens. There was a heated discussion about the Israeli occupation of West Beirut. The cover note (in Hebrew) was written by a young Benjamin Netanyahu, who was then Israel's deputy chief of mission in Washington and was present at the meeting. p. 1

Sept. 17, 1982. This document is a verbatim transcript of a meeting that took place while the massacre was in progress. Those in attendance included America's Middle East envoy, Morris Draper; Israel's defense minister, Ariel Sharon; Israel's foreign minister, Yitzhak Shamir; and several other important Israeli officials. Key passages can be found on pages 37-41 in this document viewer. p. 11

Sept. 18, 1982. This document chronicles a conversation between the American secretary of state, George P. Shultz, and the Israeli ambassador, Moshe Arens. This discussion took place on the day American officials discovered that a massacre had taken place. p. 45

A Preventable Massacre

ON the night of Sept. 16, 1982, the Israeli military allowed a right-wing Lebanese militia to enter two Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut. In the ensuing three-day rampage, the militia, linked to the Maronite Christian Phalange Party, raped, killed and dismembered at least 800 civilians, while Israeli flares illuminated the camps’ narrow and darkened alleyways. Nearly all of the dead were women, children and elderly men.

Thirty years later, the massacre at the Sabra and Shatila camps is remembered as a notorious chapter in modern Middle Eastern history, clouding the tortured relationships among Israel, the United States, Lebanon and the Palestinians. In 1983, an Israeli investigative commission concluded that Israeli leaders were “indirectly responsible” for the killings and that Ariel Sharon, then the defense minister and later prime minister, bore “personal responsibility” for failing to prevent them.

While Israel’s role in the massacre has been closely examined, America’s actions have never been fully understood. This summer, at the Israel State Archives, I found recently declassified documents that chronicle key conversations between American and Israeli officials before and during the 1982 massacre. The verbatim transcripts reveal that the Israelis misled American diplomats about events in Beirut and bullied them into accepting the spurious claim that thousands of “terrorists” were in the camps. Most troubling, when the United States was in a position to exert strong diplomatic pressure on Israel that could have ended the atrocities, it failed to do so. As a result, Phalange militiamen were able to murder Palestinian civilians, whom America had pledged to protect just weeks earlier.

Israel’s involvement in the Lebanese civil war began in June 1982, when it invaded its northern neighbor. Its goal was to root out the Palestine Liberation Organization, which had set up a state within a state, and to transform Lebanon into a Christian-ruled ally. The Israel Defense Forces soon besieged P.L.O.-controlled areas in the western part of Beirut. Intense Israeli bombardments led to heavy civilian casualties and tested even President Ronald Reagan, who initially backed Israel. In mid-August, as America was negotiating the P.L.O.’s withdrawal from Lebanon, Reagan told Prime Minister Menachem Begin that the bombings “had to stop or our entire future relationship was endangered,” Reagan wrote in his diaries.

The United States agreed to deploy Marines to Lebanon as part of a multinational force to supervise the P.L.O.’s departure, and by Sept. 1, thousands of its fighters — including Yasir Arafat — had left Beirut for various Arab countries. After America negotiated a cease-fire that included written guarantees to protect the Palestinian civilians remaining in the camps from vengeful Lebanese Christians, the Marines departed Beirut, on Sept. 10.

Israel hoped that Lebanon’s newly elected president, Bashir Gemayel, a Maronite, would support an Israeli-Christian alliance. But on Sept. 14, Gemayel was assassinated. Israel reacted by violating the cease-fire agreement. It quickly occupied West Beirut — ostensibly to prevent militia attacks against the Palestinian civilians. “The main order of the day is to keep the peace,” Begin told the American envoy to the Middle East, Morris Draper, on Sept. 15. “Otherwise, there could be pogroms.”

By Sept. 16, the I.D.F. was fully in control of West Beirut, including Sabra and Shatila. In Washington that same day, Under Secretary of State Lawrence S. Eagleburger told the Israeli ambassador, Moshe Arens, that “Israel’s credibility has been severely damaged” and that “we appear to some to be the victim of deliberate deception by Israel.” He demanded that Israel withdraw from West Beirut immediately.

In Tel Aviv, Mr. Draper and the American ambassador, Samuel W. Lewis, met with top Israeli officials. Contrary to Prime Minister Begin’s earlier assurances, Defense Minister Sharon said the occupation of West Beirut was justified because there were “2,000 to 3,000 terrorists who remained there.” Mr. Draper disputed this claim; having coordinated the August evacuation, he knew the number was minuscule. Mr. Draper said he was horrified to hear that Mr. Sharon was considering allowing the Phalange militia into West Beirut. Even the I.D.F. chief of staff, Rafael Eitan, acknowledged to the Americans that he feared “a relentless slaughter.”

On the evening of Sept. 16, the Israeli cabinet met and was informed that Phalange fighters were entering the Palestinian camps. Deputy Prime Minister David Levy worried aloud: “I know what the meaning of revenge is for them, what kind of slaughter. Then no one will believe we went in to create order there, and we will bear the blame.” That evening, word of civilian deaths began to filter out to Israeli military officials, politicians and journalists.

At 12:30 p.m. on Sept. 17, Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir hosted a meeting with Mr. Draper, Mr. Sharon and several Israeli intelligence chiefs. Mr. Shamir, having reportedly heard of a “slaughter” in the camps that morning, did not mention it.

The transcript of the Sept. 17 meeting reveals that the Americans were browbeaten by Mr. Sharon’s false insistence that “terrorists” needed “mopping up.” It also shows how Israel’s refusal to relinquish areas under its control, and its delays in coordinating with the Lebanese National Army, which the Americans wanted to step in, prolonged the slaughter.

Mr. Draper opened the meeting by demanding that the I.D.F. pull back right away. Mr. Sharon exploded, “I just don’t understand, what are you looking for? Do you want the terrorists to stay? Are you afraid that somebody will think that you were in collusion with us? Deny it. We denied it.” Mr. Draper, unmoved, kept pushing for definitive signs of a withdrawal. Mr. Sharon, who knew Phalange forces had already entered the camps, cynically told him, “Nothing will happen. Maybe some more terrorists will be killed. That will be to the benefit of all of us.” Mr. Shamir and Mr. Sharon finally agreed to gradually withdraw once the Lebanese Army started entering the city — but they insisted on waiting 48 hours (until the end of Rosh Hashana, which started that evening).

Continuing his plea for some sign of an Israeli withdrawal, Mr. Draper warned that critics would say, “Sure, the I.D.F. is going to stay in West Beirut and they will let the Lebanese go and kill the Palestinians in the camps.”

Mr. Sharon replied: “So, we’ll kill them. They will not be left there. You are not going to save them. You are not going to save these groups of the international terrorism.”

Mr. Draper responded: “We are not interested in saving any of these people.” Mr. Sharon declared: “If you don’t want the Lebanese to kill them, we will kill them.”

Mr. Draper then caught himself, and backtracked. He reminded the Israelis that the United States had painstakingly facilitated the P.L.O. exit from Beirut “so it wouldn’t be necessary for you to come in.” He added, “You should have stayed out.”

Mr. Sharon exploded again: “When it comes to our security, we have never asked. We will never ask. When it comes to existence and security, it is our own responsibility and we will never give it to anybody to decide for us.” The meeting ended with an agreement to coordinate withdrawal plans after Rosh Hashana.

By allowing the argument to proceed on Mr. Sharon’s terms, Mr. Draper effectively gave Israel cover to let the Phalange fighters remain in the camps. Fuller details of the massacre began to emerge on Sept. 18, when a young American diplomat, Ryan C. Crocker, visited the gruesome scene and reported back to Washington.

Years later, Mr. Draper called the massacre “obscene.” And in an oral history recorded a few years before his death in 2005, he remembered telling Mr. Sharon: “You should be ashamed. The situation is absolutely appalling. They’re killing children! You have the field completely under your control and are therefore responsible for that area.”

On Sept. 18, Reagan pronounced his “outrage and revulsion over the murders.” He said the United States had opposed Israel’s invasion of Beirut, both because “we believed it wrong in principle and for fear that it would provoke further fighting.” Secretary of State George P. Shultz later admitted that “we are partially responsible” because “we took the Israelis and the Lebanese at their word.” He summoned Ambassador Arens. “When you take military control over a city, you’re responsible for what happens,” he told him. “Now we have a massacre.”

But the belated expression of shock and dismay belies the Americans’ failed diplomatic effort during the massacre. The transcript of Mr. Draper’s meeting with the Israelis demonstrates how the United States was unwittingly complicit in the tragedy of Sabra and Shatila.

Ambassador Lewis, now retired, told me that the massacre would have been hard to prevent “unless Reagan had picked up the phone and called Begin and read him the riot act even more clearly than he already did in August — that might have stopped it temporarily.” But “Sharon would have found some other way” for the militiamen to take action, Mr. Lewis added.

Nicholas A. Veliotes, then the assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, agreed. “Vintage Sharon,” he said, after I read the transcript to him. “It is his way or the highway.”

The Sabra and Shatila massacre severely undercut America’s influence in the Middle East, and its moral authority plummeted. In the aftermath of the massacre, the United States felt compelled by “guilt” to redeploy the Marines, who ended up without a clear mission, in the midst of a brutal civil war.

On Oct. 23, 1983, the Marine barracks in Beirut were bombed and 241 Marines were killed. The attack led to open warfare with Syrian-backed forces and, soon after, the rapid withdrawal of the Marines to their ships. As Mr. Lewis told me, America left Lebanon “with our tail between our legs.”

The archival record reveals the magnitude of a deception that undermined American efforts to avoid bloodshed. Working with only partial knowledge of the reality on the ground, the United States feebly yielded to false arguments and stalling tactics that allowed a massacre in progress to proceed.

The lesson of the Sabra and Shatila tragedy is clear. Sometimes close allies act contrary to American interests and values. Failing to exert American power to uphold those interests and values can have disastrous consequences: for our allies, for our moral standing and most important, for the innocent people who pay the highest price of all.

|

|

Gaza-based poet remembers Sabra and Shatila massacre

Rihab Kanaan lost 51 relatives in the Tel al-Zaatar massacre in 1976

Rihab Kanaan bursts into tears while talking to Ma'an's reporter in Gaza about the trauma she suffered after losing her son and dozens of family members in the notorious Tel al-Zaatar and Sabra and Shatila massacres during Lebanon's civil war. The Gaza-based poet says the Palestinian leadership has forgotten about the Sabra and Shatila massacre in which an estimated 800-3,000 Palestinian civilians were killed by Lebanese Christian militias over a three day period on September 16, 1982. |

"I will hold two candles and a poster on which I will write: We are the martyrs of Sabra and Shatila, don’t forget us. I will stand in the Unknown Soldier Square in commemoration of my son Mahir and all martyrs," she said.

Kanaan witnessed the Tel al-Zaatar refugee camp massacre during Lebanon's civil war in 1976 and later wrote a book about the events.

She lost 51 relatives when the Beirut camp was besieged by Lebanese armed forces.

Years later, the Palestinian poet lost her son Mahir and two cousins in events in Sabra and Shatila.

"He was going to buy bread when they killed him inside the camp’s mosque before the very eyes of his sister. Up until now, when I see a mosque, I remember how Mahir died."

Kanaan was living with her second husband near the Arab University of Beirut at the time of the attack and remembers the tensions in Lebanese society.

"We knew there were signs of unrest especially after the speeches of Bachir Gemayel. Then after Gemayel was assassinated, we were sure there would be a massacre, but we never imagined it would be as horrible and as big as that," she says.

"When I was there, I heard about the massacre. I tried to go to Shatila, but I couldn't. After some effort, I managed to reach the outskirts of the camp where I saw the dead bodies and the atrocious scenes. The stories I heard from witnesses were too horrible that I couldn’t continue to listen," she recounts.

Kanaan was certain her daughter had also been killed in the massacre and amid the confusion afterwards was unable to find out what happened to her. It was only some years later that she found out that her daughter Maymana had survived the attack and was taken care of by neighbors.

Palestinian resistance fighters had already left the camp before the massacre, leaving only unarmed men, women and children, Kanaan said.

Several years after the attack, Kanaan moved to the Gaza Strip. As another anniversary of the massacre passes, she is calling upon international human rights groups, together with Arab states, to hold the perpetrators accountable.

"Two years ago, I visited Lebanon to pray to God on behalf of the martyrs from my family, and it was painful to see that nothing has changed in Sabra and Shatila," she says.

"Life is still intolerable in all refugee camps, but people are still dreaming they can return to their homeland."

The massacre took place after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, when Christian Phalangist militias entered the Beirut camp under Israeli military watch to wreak retribution for the alleged assassination of their leader Bachir Gemayel.

Over three days, Palestinian refugees were killed in droves. At the time, the number of dead was estimated at 700, but eyewitness British reporter Robert Fisk says the number is closer to 1,700.

The Palestinian Red Crescent estimates that around 3,000 civilians were killed.

Kanaan witnessed the Tel al-Zaatar refugee camp massacre during Lebanon's civil war in 1976 and later wrote a book about the events.

She lost 51 relatives when the Beirut camp was besieged by Lebanese armed forces.

Years later, the Palestinian poet lost her son Mahir and two cousins in events in Sabra and Shatila.

"He was going to buy bread when they killed him inside the camp’s mosque before the very eyes of his sister. Up until now, when I see a mosque, I remember how Mahir died."

Kanaan was living with her second husband near the Arab University of Beirut at the time of the attack and remembers the tensions in Lebanese society.

"We knew there were signs of unrest especially after the speeches of Bachir Gemayel. Then after Gemayel was assassinated, we were sure there would be a massacre, but we never imagined it would be as horrible and as big as that," she says.

"When I was there, I heard about the massacre. I tried to go to Shatila, but I couldn't. After some effort, I managed to reach the outskirts of the camp where I saw the dead bodies and the atrocious scenes. The stories I heard from witnesses were too horrible that I couldn’t continue to listen," she recounts.

Kanaan was certain her daughter had also been killed in the massacre and amid the confusion afterwards was unable to find out what happened to her. It was only some years later that she found out that her daughter Maymana had survived the attack and was taken care of by neighbors.

Palestinian resistance fighters had already left the camp before the massacre, leaving only unarmed men, women and children, Kanaan said.

Several years after the attack, Kanaan moved to the Gaza Strip. As another anniversary of the massacre passes, she is calling upon international human rights groups, together with Arab states, to hold the perpetrators accountable.

"Two years ago, I visited Lebanon to pray to God on behalf of the martyrs from my family, and it was painful to see that nothing has changed in Sabra and Shatila," she says.

"Life is still intolerable in all refugee camps, but people are still dreaming they can return to their homeland."

The massacre took place after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, when Christian Phalangist militias entered the Beirut camp under Israeli military watch to wreak retribution for the alleged assassination of their leader Bachir Gemayel.

Over three days, Palestinian refugees were killed in droves. At the time, the number of dead was estimated at 700, but eyewitness British reporter Robert Fisk says the number is closer to 1,700.

The Palestinian Red Crescent estimates that around 3,000 civilians were killed.

Official: 30 years after camp massacre, justice still elusive

A Palestinian woman places a flower at the Palestinian Martyr's cemetery at Shatila refugee camp in Beirut, to mark the 2011 anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. The Arabic words read "The martyrs of Sabra and Shatila massacre, 1982

On the 30th anniversary of the massacre of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon's Sabra and Shatila camp, a Palestinian official stressed that no one has been brought to justice.

"Those responsible for slaughtering thousands have not been punished and Palestinian refugees continue to be denied their homeland," PLO official Saeb Erekat said in a statement Sunday.

He urged the international community to ensure that the rights of Palestinian refugees to "return, restitution and compensation" are respected.

He continued: "In 1982, foreign reporters wrote: 'How many Sabras and how many Shatilas will be needed for the world to put an end to this injustice?' Since 1982, many Sabras and Shatilas have occurred and they all have the same components: blood and impunity."

The massacre took place after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, when Christian Phalangist militias entered the Beirut camp under Israeli military watch to wreak retribution for the alleged assassination of their leader Bachir Gemayel.

Over three days, Palestinian refugees were killed in droves. At the time, the number of dead was estimated at 700, but eyewitness British reporter Robert Fisk says the number is closer to 1,700.

The Palestinian Red Crescent estimates that 3,000 civilians were killed.

Israeli soldiers in control of the perimeter of the camps did not stop the slaughter, firing flares overhead at night to aid the Phalangist gunmen.

An Israeli investigation found then defense minister Ariel Sharon guilty of failing to prevent the deaths of innocent civilians. He was demoted but later became Israeli prime minister.

The Phalangist leadership never apologized for their involvement in the massacre, one of the bloodiest events in Lebanon's 15-year civil war which claimed 150,000 lives.

On the 30th anniversary of the massacre of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon's Sabra and Shatila camp, a Palestinian official stressed that no one has been brought to justice.

"Those responsible for slaughtering thousands have not been punished and Palestinian refugees continue to be denied their homeland," PLO official Saeb Erekat said in a statement Sunday.

He urged the international community to ensure that the rights of Palestinian refugees to "return, restitution and compensation" are respected.

He continued: "In 1982, foreign reporters wrote: 'How many Sabras and how many Shatilas will be needed for the world to put an end to this injustice?' Since 1982, many Sabras and Shatilas have occurred and they all have the same components: blood and impunity."

The massacre took place after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, when Christian Phalangist militias entered the Beirut camp under Israeli military watch to wreak retribution for the alleged assassination of their leader Bachir Gemayel.

Over three days, Palestinian refugees were killed in droves. At the time, the number of dead was estimated at 700, but eyewitness British reporter Robert Fisk says the number is closer to 1,700.

The Palestinian Red Crescent estimates that 3,000 civilians were killed.

Israeli soldiers in control of the perimeter of the camps did not stop the slaughter, firing flares overhead at night to aid the Phalangist gunmen.

An Israeli investigation found then defense minister Ariel Sharon guilty of failing to prevent the deaths of innocent civilians. He was demoted but later became Israeli prime minister.

The Phalangist leadership never apologized for their involvement in the massacre, one of the bloodiest events in Lebanon's 15-year civil war which claimed 150,000 lives.

15 sept 2012

The forgotten massacre

Thirty years after 1,700 Palestinians were killed at the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps, Robert Fisk revisits the killing fields.

The memories remain, of course. The man who lost his family in an earlier massacre, only to watch the young men of Chatila lined up after the new killings and marched off to death. But – like the muck piled on the garbage tip amid the concrete hovels – the stench of injustice still pervades the camps where 1,700 Palestinians were butchered 30 years ago next week. No-one was tried and sentenced for a slaughter, which even an Israeli writer at the time compared to the killing of Yugoslavs by Nazi sympathisers in the Second World War. Sabra and Chatila are a memorial to criminals who evaded responsibility, who got away with it.

Khaled Abu Noor was in his teens, a would-be militiaman who had left the camp for the mountains before Israel's Phalangist allies entered Sabra and Chatila. Did this give him a guilty conscience, that he was not there to fight the rapists and murderers? "What we all feel today is depression," he said. "We demanded justice, international trials – but there was nothing. Not a single person was held responsible. No-one was put before justice. And so we had to suffer in the 1986 camps war (at the hands of Shia Lebanese) and so the Israelis could slaughter so many Palestinians in the 2008-9 Gaza war. If there had been trials for what happened here 30 years ago, the Gaza killings would not have happened."

He has a point, of course. While presidents and prime ministers have lined up in Manhattan to mourn the dead of the 2001 international crimes against humanity at the World Trade Centre, not a single Western leader has dared to visit the dank and grubby Sabra and Chatila mass graves, shaded by a few scruffy trees and faded photographs of the dead. Nor, let it be said – in 30 years – has a single Arab leader bothered to visit the last resting place of at least 600 of the 1,700 victims. Arab potentates bleed in their hearts for the Palestinians but an airfare to Beirut might be a bit much these days – and which of them would want to offend the Israelis or the Americans?

It is an irony – but an important one, nonetheless – that the only nation to hold a serious official enquiry into the massacre, albeit flawed, was Israel. The Israeli army sent the killers into the camps and then watched – and did nothing – while the atrocity took place. A certain Israeli Lieutenant Avi Grabowsky gave the most telling evidence of this. The Kahan Commission held the then defence minister Ariel Sharon personally responsible, since he sent the ruthless anti-Palestinian Phalangists into the camps to "flush out terrorists" – "terrorists" who turned out to be as non-existent as Iraq's weapons of mass destruction 21 years later.

Sharon lost his job but later became prime minister, until broken by a stroke which he survived – but which took from him even the power of speech. Elie Hobeika, the Lebanese Christian militia leader who led his murderers into the camp – after Sharon had told the Phalange that Palestinians had just assassinated their leader, Bashir Gemayel – was murdered years later in east Beirut. His enemies claimed the Syrians killed him, his friends blamed the Israelis; Hobeika, who had "gone across" to the Syrians, had just announced he would "tell all" about the Sabra and Chatila atrocity at a Belgian court, which wished to try Sharon.

Of course, those of us who entered the camps on the third and final day of the massacre – 18 September, 1982 – have our own memories. I recall the old man in pyjamas lying on his back on the main street with his innocent walking stick beside him, the two women and a baby shot next to a dead horse, the private house in which I sheltered from the killers with my colleague Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post – only to find a dead young woman lying in the courtyard beside us. Some of the women had been raped before their killing. The armies of flies, the smell of decomposition. These things one remembers.

Abu Maher is 65 – like Khaled Abu Noor, his family originally fled their homes in Safad in present-day Israel – and stayed in the camp throughout the massacre, at first disbelieving the women and children who urged him to run from his home. "A woman neighbour started screaming and I looked out and saw her shot dead and her daughter tried to run away and the killers chased her, saying "Kill her, kill her, don't let her go!" She shouted to me and I could do nothing. But she escaped."

Repeated trips back to the camp, year after year, have built up a narrative of astonishing detail. Investigations by Karsten Tveit of Norwegian radio and myself proved that many men, seen by Abu Maher being marched away alive after the initial massacre, were later handed by the Israelis back to the Phalangist killers – who held them prisoner for days in eastern Beirut and then, when they could not swap them for Christian hostages, executed them at mass graves.

And the arguments in favour of forgetfulness have been cruelly deployed. Why remember a few hundred Palestinians slaughtered when 25,000 have been killed in Syria in 19 months?

Supporters of Israel and critics of the Muslim world have written to me in the last couple of years, abusing me for referring repeatedly to the Sabra and Chatila massacre, as if my own eye-witness account of this atrocity has – like a war criminal – a statute of limitations. Given these reports of mine (compared to my accounts of Turkish oppression) one reader has written to me that "I would conclude that, in this case (Sabra and Chatila), you have an anti-Israeli bias. This is based solely on the disproportionate number of references you make to this atrocity…"

But can one make too many? Dr Bayan al-Hout, widow of the PLO's former ambassador to Beirut, has written the most authoritative and detailed account of the Sabra and Chatila war crimes – for that is what they were – and concludes that in the years that followed, people feared to recall the event. "Then international groups started talking and enquiring. We must remember that all of us are responsible for what happened. And the victims are still scarred by these events – even those who are unborn will be scarred – and they need love." In the conclusion to her book, Dr al-Hout asks some difficult – indeed, dangerous – questions: "Were the perpetrators the only ones responsible? Were the people who committed the crimes the only criminals? Were even those who issued the orders solely responsible? Who in truth is responsible?"

In other words, doesn't Lebanon bear responsibility with the Phalangist Lebanese, Israel with the Israeli army, the West with its Israeli ally, the Arabs with their American ally? Dr al-Hout ends her investigation with a quotation from Rabbi Abraham Heschel who raged against the Vietnam war. "In a free society," the Rabbi said, "some are guilty, but all are responsible."