7 nov 2009

A collection of articles and papers on the massacre, including testimonies of survivors:

“29 October 1956: Israeli frontier guards started at 4 pm what they called a tour of the Triangle Villages. They told the Mukhtars (Aldermen) of those villages that the curfew from that day onwards was to start from 5 pm instead of 6 pm. They reached Kafr Qasem around 4:45 and informed the Mukhtar protested that there are about 400 villagers working outside the village and there is not enough time to inform them of the new times. An officer assured him that they will be taken care of. Then the guards waited at the entrance to the village.

43 Kafr Qasem inhabitants were massacred in cold blood by the army as they returned from work, their crime was violating a curfew they did not know about. On the northern entrance of the village 3 were killed and 2 were killed inside of the village. Amongst the dead were men, women, and children. Lutanat Danhan was touring the area in his jeep reporting the massacre, on his wireless he said “minus 15 Arabs” after a while his message on the radio to his H.Q. was “it is difficult to count”.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/5/

Kfar Kassem Massacre “In this way were the 49 inhabitants of Kafr Kassem slaughtered”

“29 October 1956: Israeli frontier guards started at 4 pm what they called a tour of the Triangle Villages. They told the Mukhtars (Aldermen) of those villages that the curfew from that day onwards was to start from 5 pm instead of 6 pm. They reached Kafr Qasem around 4:45 and informed the Mukhtar protested that there are about 400 villagers working outside the village and there is not enough time to inform them of the new times. An officer assured him that they will be taken care of. Then the guards waited at the entrance to the village.

43 Kafr Qasem inhabitants were massacred in cold blood by the army as they returned from work, their crime was violating a curfew they did not know about. On the northern entrance of the village 3 were killed and 2 were killed inside of the village. Amongst the dead were men, women, and children. Lutanat Danhan was touring the area in his jeep reporting the massacre, on his wireless he said “minus 15 Arabs” after a while his message on the radio to his H.Q. was “it is difficult to count”.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/5/

Kfar Kassem Massacre “In this way were the 49 inhabitants of Kafr Kassem slaughtered”

The following is a detailed account of the horrible massacre of Kfar Kassem as told by eyewitnesses. The Israeli daily, Kol Haam published on Wednesday, December 19, 1956 on its front page the following detailed story of the Kfar Kassem massacre, which was committed by the Israeli army on October 29, 1956, against the Arabs in occupied Palestine. Forty-nine men, women and children were slaughtered in cold blood. Kol Haam published the story of the massacre under the title, “In This Way Were the 49 Inhabitants of Kfar Kassem Slaughtered.”

The following is a literal translation: Here are the details of the massacre in which 49 of the peaceful inhabitants of Kfar Kassem– all Arabs living in Israel– were slaughtered in cold blood. Another thirteen of these inhabitants also sustained serious injuries in this horrible massacre committed by the troops of the Israeli frontier guards.

On October 29, 1956, the day on which Israel launched its assault on Egypt, units of the Israeli frontier guards started at 4 p.m. what they called a tour of the Triangle Villages. They informed the Mukhtars (heads of the villages) and the rural councils that the curfew in those villages was from that day onwards to be observed from 5 p.m. instead of 6 p.m. as was the case before, and that the inhabitants were, therefore, requested to stay home as from that very instant.

One of the villages the frontier guards passed through was Kfar Kassem. This is a small Arab village situated near the Israeli settlement of Betah Tefka. The villagers there received the alert at 4:45 p.m., only 15 minutes before the new curfew time. The “Mukhtar” of Kfar Kassem promptly informed the unit officer that a large number of the villagers, whose work took them outside the village, knew nothing of this curfew. The officer in charge replied that his soldiers would take care of these. The villagers who were home complied with the newly-imposed curfew and remained indoors. Meanwhile, the armed frontier guards posted themselves at the village gates. Before long, the first batch of villagers came into sight. The first to arrive was a group of four laborers, home-bound, on bicycles. Here is what one of these laborers, Abdullah Samir Bedir by name, said about this incident:

“We reached the village entrance at about 4:55 p.m. We were suddenly confronted by a frontier unit consisting of 12 men and an officer, all occupying an army truck. We greeted the officer in Hebrew saying ‘Shalom Katsin’ which means ‘Peace be unto you officer,’ to which he gave no reply. He then asked us in Arabic: ‘Are you happy?’ and we said, ‘Yes.’ The soldiers then started stepping down from the truck and the officer ordered us to line up.

Then he shouted to his soldiers this order: ‘Laktasour Otem,’ which means ‘Reap them!’ The soldiers opened fire, but by then I had flung myself on the ground, and started rolling, yelling as I rolled over. Then I feigned death. Meanwhile, the soldiers had so riddled the bodies of my three friends with bullets that the officer in charge ordered them to cease firing, adding that the bullets were merely being wasted. As he put it, we had more than the necessary dose of those deadly bullets.

“All this occurred while I lay very still, feigning death. Then I saw three laborers approaching on a small horse cart. The soldiers stopped the cart and killed all three of them. Soon after, the soldiers moved a few yards down the road, apparantly to take up positions that would enable them to stop a new truckload of home-bound villager, as well as a bunch of workers returning home on their bicycles. I seized this opportunity and moved as quickly as I could to the nearest house. The soldiers saw me and opened fire, but I was already in safety.

“One of the trucks used for transporting farm produce was again stopped while carrying thirteen olive pickers, all women and girls, and two male laborers and the driver. They were attacked by the same group of frontier guards, who pitilessly butchered all but one of them.”

This is what 16-year-old Hanna Soliman Amer, the only survivor, said about this incident: “The soldiers brought our car to a halt at the entrance of the village and ordered the two workers and the driver to step down. Then they told them they were going to be killed. On hearing that the women started crying and screaming, begging the soldiers to spare those poor workers’ lives. But the soldiers shouted at the women, saying that their turn was coming and that they, too, were going to be killed.

“The soldiers stared at the women for a few moments, as if waiting for their officer to give the order. Then I heard the officer talk over the wireless set, apparantly asking the headquarters for instructions about the women. The minute the wireless conversation was over, the soldiers took aim at the women and girls, who were 13 in number, and who included pregnant ones (Fatma Dawoud Sarsour was in her eighth month pregnancy) as well as an old woman of sixty and two thirteen-year-old girls (Latifa Eissa and Rashika Bedair).”

The number of cars stopped by the Israeli soldiers of the frontier guards was three; the people in all three cars were ordered to descend and were shot by machine-gun fire, killing them instantly.

A fourth car, which was a little late in coming, met with better luck, for the driver, seeing the bodies scattered around, didn’t heed the order to stop. He pressed the accelerator and thus managed to escape with his car. The soldiers, however, succeeded in shooting one of the passengers as the care sped by.

With the massacre practically over, the soldiers moved around finishing off whoever still had a pulse beating in him. Later on, the examination of these bodies showed that the soldiers mutilated them, smashing the heads and cutting open the abdomens of some of the wounded women to finish them off.

The only survivors were those who for some time lay buried under the corpses of their comrades and thus had their bodies covered with the blood of these victims, giving the impression that they, too, were dead. Those were the only ones who lived to speak of the horrors of the massacre of Kfar Kassem.

The massacre lasted for an hour and a half and the soldiers looted whatever they could find, apparently while going round the bodies doing their finishing-off job. However, thirteen of those wretched people only fainted when they were shot at. These were taken to Bilinson as well as to other hospitals.

One of those wounded was Osman Selim, who was travelling on one of the trucks. He witnessed the massacre, and escaped by pretending to be dead among the pile of corpses. Assad Selim, a cyclist, was seriously injured. So was Abdel Rahman Yacoub Sarsoura, a youth aged 16, who is deaf and dumb. The only one who managed to escape death and reach Kroum El-Zeitoum is Ismail Akab Badeera, aged 18, who nursed his wounds until he got there, then climbing up an olive tree despite his suffering. He remained there for two whole days until a passing shepherd came along and carried him to a hospital where one of his legs had to be amputated for gangrene.

The blood bath was not restricted to the entrance or outskirts, but was carried right into the village itself. Talal Shaker Eissa, aged 8, left his home to bring in a flock of goats. He had hardly stepped out of his home when he was murdered by a shot fired by one of the soldiers. When his father ran out to investigate, he was killed by another shot. The mother, dragging in his body, was then shot. Noura, the remaining child, followed the cries of agony coming from her parents, and was killed on the spot by a hail of bullets. The only survivor of the family, a frail and aged grandfather, hearing the horror and the sounds of death, succumbed to a heart attack and died.

The next day, 31 October, 1956, a curfew was imposed on the village of Kfar Kassem, and during that time, the Israeli police brought over some of the villagers form (neighboring) Galgoulia and ordered them to bury the corpses, which included fathers, mothers, sons and daughters. Among these were Safa Abdalla Sarour, a woman aged 45, who was killed with her two sons, Jihad, 16, and Abdalla, 14. Osman Abdalla Eissa was killed with his son Fathi aged 12; and Zeinab Abdel Rahman Taha and her daughter Bikria, aged 17. http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/3/

Kufr Qassem: 40 Years Later And The Wounds Are Still Fresh, Survivors Of Horrible Massacre

The following is a literal translation: Here are the details of the massacre in which 49 of the peaceful inhabitants of Kfar Kassem– all Arabs living in Israel– were slaughtered in cold blood. Another thirteen of these inhabitants also sustained serious injuries in this horrible massacre committed by the troops of the Israeli frontier guards.

On October 29, 1956, the day on which Israel launched its assault on Egypt, units of the Israeli frontier guards started at 4 p.m. what they called a tour of the Triangle Villages. They informed the Mukhtars (heads of the villages) and the rural councils that the curfew in those villages was from that day onwards to be observed from 5 p.m. instead of 6 p.m. as was the case before, and that the inhabitants were, therefore, requested to stay home as from that very instant.

One of the villages the frontier guards passed through was Kfar Kassem. This is a small Arab village situated near the Israeli settlement of Betah Tefka. The villagers there received the alert at 4:45 p.m., only 15 minutes before the new curfew time. The “Mukhtar” of Kfar Kassem promptly informed the unit officer that a large number of the villagers, whose work took them outside the village, knew nothing of this curfew. The officer in charge replied that his soldiers would take care of these. The villagers who were home complied with the newly-imposed curfew and remained indoors. Meanwhile, the armed frontier guards posted themselves at the village gates. Before long, the first batch of villagers came into sight. The first to arrive was a group of four laborers, home-bound, on bicycles. Here is what one of these laborers, Abdullah Samir Bedir by name, said about this incident:

“We reached the village entrance at about 4:55 p.m. We were suddenly confronted by a frontier unit consisting of 12 men and an officer, all occupying an army truck. We greeted the officer in Hebrew saying ‘Shalom Katsin’ which means ‘Peace be unto you officer,’ to which he gave no reply. He then asked us in Arabic: ‘Are you happy?’ and we said, ‘Yes.’ The soldiers then started stepping down from the truck and the officer ordered us to line up.

Then he shouted to his soldiers this order: ‘Laktasour Otem,’ which means ‘Reap them!’ The soldiers opened fire, but by then I had flung myself on the ground, and started rolling, yelling as I rolled over. Then I feigned death. Meanwhile, the soldiers had so riddled the bodies of my three friends with bullets that the officer in charge ordered them to cease firing, adding that the bullets were merely being wasted. As he put it, we had more than the necessary dose of those deadly bullets.

“All this occurred while I lay very still, feigning death. Then I saw three laborers approaching on a small horse cart. The soldiers stopped the cart and killed all three of them. Soon after, the soldiers moved a few yards down the road, apparantly to take up positions that would enable them to stop a new truckload of home-bound villager, as well as a bunch of workers returning home on their bicycles. I seized this opportunity and moved as quickly as I could to the nearest house. The soldiers saw me and opened fire, but I was already in safety.

“One of the trucks used for transporting farm produce was again stopped while carrying thirteen olive pickers, all women and girls, and two male laborers and the driver. They were attacked by the same group of frontier guards, who pitilessly butchered all but one of them.”

This is what 16-year-old Hanna Soliman Amer, the only survivor, said about this incident: “The soldiers brought our car to a halt at the entrance of the village and ordered the two workers and the driver to step down. Then they told them they were going to be killed. On hearing that the women started crying and screaming, begging the soldiers to spare those poor workers’ lives. But the soldiers shouted at the women, saying that their turn was coming and that they, too, were going to be killed.

“The soldiers stared at the women for a few moments, as if waiting for their officer to give the order. Then I heard the officer talk over the wireless set, apparantly asking the headquarters for instructions about the women. The minute the wireless conversation was over, the soldiers took aim at the women and girls, who were 13 in number, and who included pregnant ones (Fatma Dawoud Sarsour was in her eighth month pregnancy) as well as an old woman of sixty and two thirteen-year-old girls (Latifa Eissa and Rashika Bedair).”

The number of cars stopped by the Israeli soldiers of the frontier guards was three; the people in all three cars were ordered to descend and were shot by machine-gun fire, killing them instantly.

A fourth car, which was a little late in coming, met with better luck, for the driver, seeing the bodies scattered around, didn’t heed the order to stop. He pressed the accelerator and thus managed to escape with his car. The soldiers, however, succeeded in shooting one of the passengers as the care sped by.

With the massacre practically over, the soldiers moved around finishing off whoever still had a pulse beating in him. Later on, the examination of these bodies showed that the soldiers mutilated them, smashing the heads and cutting open the abdomens of some of the wounded women to finish them off.

The only survivors were those who for some time lay buried under the corpses of their comrades and thus had their bodies covered with the blood of these victims, giving the impression that they, too, were dead. Those were the only ones who lived to speak of the horrors of the massacre of Kfar Kassem.

The massacre lasted for an hour and a half and the soldiers looted whatever they could find, apparently while going round the bodies doing their finishing-off job. However, thirteen of those wretched people only fainted when they were shot at. These were taken to Bilinson as well as to other hospitals.

One of those wounded was Osman Selim, who was travelling on one of the trucks. He witnessed the massacre, and escaped by pretending to be dead among the pile of corpses. Assad Selim, a cyclist, was seriously injured. So was Abdel Rahman Yacoub Sarsoura, a youth aged 16, who is deaf and dumb. The only one who managed to escape death and reach Kroum El-Zeitoum is Ismail Akab Badeera, aged 18, who nursed his wounds until he got there, then climbing up an olive tree despite his suffering. He remained there for two whole days until a passing shepherd came along and carried him to a hospital where one of his legs had to be amputated for gangrene.

The blood bath was not restricted to the entrance or outskirts, but was carried right into the village itself. Talal Shaker Eissa, aged 8, left his home to bring in a flock of goats. He had hardly stepped out of his home when he was murdered by a shot fired by one of the soldiers. When his father ran out to investigate, he was killed by another shot. The mother, dragging in his body, was then shot. Noura, the remaining child, followed the cries of agony coming from her parents, and was killed on the spot by a hail of bullets. The only survivor of the family, a frail and aged grandfather, hearing the horror and the sounds of death, succumbed to a heart attack and died.

The next day, 31 October, 1956, a curfew was imposed on the village of Kfar Kassem, and during that time, the Israeli police brought over some of the villagers form (neighboring) Galgoulia and ordered them to bury the corpses, which included fathers, mothers, sons and daughters. Among these were Safa Abdalla Sarour, a woman aged 45, who was killed with her two sons, Jihad, 16, and Abdalla, 14. Osman Abdalla Eissa was killed with his son Fathi aged 12; and Zeinab Abdel Rahman Taha and her daughter Bikria, aged 17. http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/3/

Kufr Qassem: 40 Years Later And The Wounds Are Still Fresh, Survivors Of Horrible Massacre

It was a 90-minute drive from Jerusalem to the town of Kufr Qassem in the Palestinian triangle inside Israel proper. I had arranged a number of interviews with survivors of a massacre the Israeli army committed four decades ago. The road leading into the town was full of olive trees on both sides. Only a few people were collecting their olives. The harvest was close to its end. And so it was those days forty years ago.

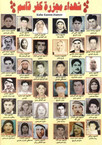

On 29 October 1956, just hours after the tripartite attack of Israel, France and Britain started on Egypt in what was known as the Sinai Campaign, 49 villagers from Kufr Qassem were slaughtered in cold blood as they made their way back from their fields to their homes. In the town center stood a monument commemorating those who were killed.

The list of names carved on the big square stone gave all 49 names and a blank space was left without any name. I later was told it was left for the 50th victim whose name nobody could tell. One of the murdered women was pregnant in her eighth month and the baby died in her womb. No one could ever come up with a suitable name to that unborn victim.

I went through the list and matched it with names of people who were slated for interviews later in the day. Many names sounded familiar. Many of them were relatives of some of those I was going to see. The view of those picking their olives whom I saw on my way into the town crossed my mind to intercut later with images of those who returned to their homes on the day of the massacre. The scene moved me and I felt teardrops were about to roll down my face. At that moment, rain started to fall, lightly first and later very heavily. The sky. I wondered, was crying in Kufr Qassem!

Israel did not spare any effort to hide the crime and to cover up for those who committed it. The strict censorship it clamped on the story lasted for only a week. On 6 November 1956, one Israeli newspaper reported that a commission of inquiry “was set to investigate the incidents in Kufr Qassem where some civilians were killed and others wounded during a curfew in Kufr Qassem.” A month and a half later, details on the massacre started to flow in through the media. A number of left wing and Arab Knesset members played a leading role and contributed to the exposure. Tewfiq Toubi and Meir Wilner of the Israeli Communist Party sent hundreds of letters about the events on that day to public figures in the country.

Latif Dori, an active member of left-wing Zionist Mapam Party infiltrated into the village three days after the massacre and collected first hand testimonies from survivors. Uri Avneri, also a leading leftist who was the first to visit PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat in Beirut during the Israeli siege of the Lebanese capital in 1982, played an effective role through his weekly magazine, Ha’Oiam Hazeh (This World.) Yet all what was published in those days could not give an exact account of the motives behind the massacre. The villagers gave the only explanation. They insisted the slaughtering of innocent villagers was meant to force them out of their country into Jordan. Kufr Qassem was no more than ten kilometers away from the 1967 borders between Israel and Jordan.

Only in 1991, part of the truth started to come out. Rupik Rozenthal, an Israeli journalist, wrote in “Hadashot” on 25 November saying the massacre was part of an overall plan by the Israeli army to deport as many Palestinians as possible out of the country. Rozenthal was allowed to go through the army archives and read the minutes of the military trial of the 11 soldiers and officers who were involved in the massacre. He found out that the plan was to try and move the Palestinians out of the Arab villages in the Triangle and send them into Jordan should the latter intervenes in support for Egypt. Jordan did not enter the 1956 war. The plan was not carried out in full. Only the first phase was done. The dire price was 49 villagers from Kufr Qassem.

When the crime was too heinous to hide, Israel decided to put those involved on military trial, which according to the villagers was no more than a joke. Colonel Yishishkar Shedmi, who changed the timing for the curfew and reportedly gave his soldiers the green light to go ahead with the massacre, was only found guilty of exceeding his authority when he moved the curfew hour.

The court fined him one piaster fine only. The verdict, at least as far as the villagers were concerned, meant that the one piaster was the price Israel was ready to give for the 49 victims. The rest of those on trial were sentenced between seven to 17 years imprisonment but all were released before the end of the third year of their penalty. Major Avraham Melinki, who commanded the Border Police force in the village and was the one who gave the orders to shoot, was promoted right after his release from prison. Then Prime Minister and Defense Minister David Ben Gurion placed him in charge of security arrangements in Israel’s maximum-security nuclear reactor in Dimona. Colonel Shedmi continued his service in the army. In 1967, he was a mechanized brigade commander and in 1973 he served as advisor to the commander of the northern district and was wounded when their helicopter crashed over Mount of Hermon on the Golan Heights.

On 29 October 1956, just hours after the tripartite attack of Israel, France and Britain started on Egypt in what was known as the Sinai Campaign, 49 villagers from Kufr Qassem were slaughtered in cold blood as they made their way back from their fields to their homes. In the town center stood a monument commemorating those who were killed.

The list of names carved on the big square stone gave all 49 names and a blank space was left without any name. I later was told it was left for the 50th victim whose name nobody could tell. One of the murdered women was pregnant in her eighth month and the baby died in her womb. No one could ever come up with a suitable name to that unborn victim.

I went through the list and matched it with names of people who were slated for interviews later in the day. Many names sounded familiar. Many of them were relatives of some of those I was going to see. The view of those picking their olives whom I saw on my way into the town crossed my mind to intercut later with images of those who returned to their homes on the day of the massacre. The scene moved me and I felt teardrops were about to roll down my face. At that moment, rain started to fall, lightly first and later very heavily. The sky. I wondered, was crying in Kufr Qassem!

Israel did not spare any effort to hide the crime and to cover up for those who committed it. The strict censorship it clamped on the story lasted for only a week. On 6 November 1956, one Israeli newspaper reported that a commission of inquiry “was set to investigate the incidents in Kufr Qassem where some civilians were killed and others wounded during a curfew in Kufr Qassem.” A month and a half later, details on the massacre started to flow in through the media. A number of left wing and Arab Knesset members played a leading role and contributed to the exposure. Tewfiq Toubi and Meir Wilner of the Israeli Communist Party sent hundreds of letters about the events on that day to public figures in the country.

Latif Dori, an active member of left-wing Zionist Mapam Party infiltrated into the village three days after the massacre and collected first hand testimonies from survivors. Uri Avneri, also a leading leftist who was the first to visit PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat in Beirut during the Israeli siege of the Lebanese capital in 1982, played an effective role through his weekly magazine, Ha’Oiam Hazeh (This World.) Yet all what was published in those days could not give an exact account of the motives behind the massacre. The villagers gave the only explanation. They insisted the slaughtering of innocent villagers was meant to force them out of their country into Jordan. Kufr Qassem was no more than ten kilometers away from the 1967 borders between Israel and Jordan.

Only in 1991, part of the truth started to come out. Rupik Rozenthal, an Israeli journalist, wrote in “Hadashot” on 25 November saying the massacre was part of an overall plan by the Israeli army to deport as many Palestinians as possible out of the country. Rozenthal was allowed to go through the army archives and read the minutes of the military trial of the 11 soldiers and officers who were involved in the massacre. He found out that the plan was to try and move the Palestinians out of the Arab villages in the Triangle and send them into Jordan should the latter intervenes in support for Egypt. Jordan did not enter the 1956 war. The plan was not carried out in full. Only the first phase was done. The dire price was 49 villagers from Kufr Qassem.

When the crime was too heinous to hide, Israel decided to put those involved on military trial, which according to the villagers was no more than a joke. Colonel Yishishkar Shedmi, who changed the timing for the curfew and reportedly gave his soldiers the green light to go ahead with the massacre, was only found guilty of exceeding his authority when he moved the curfew hour.

The court fined him one piaster fine only. The verdict, at least as far as the villagers were concerned, meant that the one piaster was the price Israel was ready to give for the 49 victims. The rest of those on trial were sentenced between seven to 17 years imprisonment but all were released before the end of the third year of their penalty. Major Avraham Melinki, who commanded the Border Police force in the village and was the one who gave the orders to shoot, was promoted right after his release from prison. Then Prime Minister and Defense Minister David Ben Gurion placed him in charge of security arrangements in Israel’s maximum-security nuclear reactor in Dimona. Colonel Shedmi continued his service in the army. In 1967, he was a mechanized brigade commander and in 1973 he served as advisor to the commander of the northern district and was wounded when their helicopter crashed over Mount of Hermon on the Golan Heights.

Testimonies of survivors:

1-Jamal Freij was 17 years old the day the massacre took place. He was among a number of villagers working their fields. Among their group, there were some 25 girls and women. “Two kids from the village came to notify us that curfew hour was moved earlier to five in the afternoon. I told the women to head back to their homes. I went, along with a number of men, to a warehouse to change our clothes.

On our way back, and at a distance of two kilometers, we heard heavy shooting coming from the village direction. We started to retreat but a lorry driver who came rushing towards the village told us there was no need to run away simply because, he thought and we believed, the shooting was not that serious or indiscriminate. At the entrance to the village, three soldiers stopped us.

Their officer ordered us to get out of the lorry, which drove us to the village. The minute we told him we all were from Kufr Qassem he ordered his soldiers to open fire. They shot at us. Many fell on the ground, dead or wounded. I was among a number of men who ran away but I fell a minute later and hid myself behind the lorry’s wheel until the soldiers discovered me late at night and took me back to the village.”

2-Talal Issa Shaker was eight years only. Villagers still remember the tragedy that involved his death. He went out to return the flock of sheep from the neighboring fields. A villager I met confirmed that the soldiers “saw Talal and shot him dead. When his father went out to check what was happening, they soldiers shot and seriously wounded him. The mother later went out and was shot and so was the daughter, Noura.”

3-Mustafa Khamis Amer is now 58 years old. He explains how he miraculously escaped death: “The soldiers at the southern entrance to the village stopped us and checked our identity cards. Immediately afterwards, their officer ordered them to shoot. I started to run away and managed to disappear from them while many others were shot dead or wounded.” On that day, Mustafa added, villagers from nearby Jaijoulya were brought in by the army to dig a huge hole, which at the time they never knew it was meant to become the collective grave for the victims. All bodies were put in nylon bags and put aside ready for burial, he said.

4-Saleh Khalil Issa was 19 years old. His testimony, given in detail to Latif Dori three days after the massacre, gave the following account: “We were heading back to the village on our bicycles. We arrived at about ten to five in the afternoon. Three soldiers at the western entrance to the village ordered us to stop. Each of us put his hand in his pocket to pull out his identity card but the officer did not wait. He gave orders to open fire. They shot and immediately killed my cousin Abed Salim Issa and injured his brother Asaad and myself. We fell on the ground and then we saw another group of people riding their bicycles approaching. They were a group of eleven people, whose names are known to me. I heard the officer giving orders using a term HARVEST THEM and they opened fire. We fell on the ground.

I saw a car approaching driven by Ata Yaacob who had some passengers with him. They all were ordered to step out of the car and to stand in a queue. The officer again used the same term and fire was opened at them. The soldiers then pulled all bodies to a nearby field. At a certain moment, we found out the soldiers were looking in the opposite direction and we started to run away. We ran for some 50 metres and fire was shot at us again. I took the ground and stayed there until the next morning. Throughout the night, I heard soldiers giving instructions to move the bodies. In the morning, the soldiers saw me and took me to the hospital.

5-Abdul Rahim Sarsour was also 17 years old on that day. He remembers how he was injured on his way back to the village when soldiers opened fire at him and at the group that returned with him. He pretended he was dead to escape being shot at again by the soldiers. He said he still feels guilty for the death of his brother, whom their mother sent to inform Abdul Rahim and the others that the curfew hour was changed. “Had he stayed home, he would be alive today,”said Abdul Rahim who gave the following account: “We arrived in the village. Soldiers were manning a roadblock on the entrance. They ordered us out of the car.

An officer then gave his orders to HARVEST US and fire was opened indiscriminately in our direction. I fell on the ground and so did many others, some were killed immediately and others wounded. My brother fell next to me. He murmured asking if I was hit. I gave him a blow with my elbow to remain silent but it was too late. A soldier approached and fired four bullets at me, hitting both my right leg and arm. The soldier then pointed his gun to my brother’s head and fired several rounds of bullets. The head exploded in pieces while I was watching but did not dare say a single word.

I cannot forget that moment at all. I still remember how my brother, frightened by the soldiers, was pressing with his hands on my chest. When the soldier fire at him, I felt the pressure increasing for a second or two until his hands went loose. Jum’ah Sarsour, another wounded. lay next to me. He was moaning with pain. I tried to ask him to remain silent but it was too late too. One of the soldiers drew close to him and shot him dead. A third main badly wounded was screaming at the soldiers. A soldier approached him and shouted WHY ARE YOU SHOUTING, YOU SON-OF-A-BITCH and shot him dead.

A car approached with a number of women aboard singing. One of the girls saw the bodies and yelled on the rest to stop singing. The driver sped away from the scene but some 150 meters away we heard plenty of shooting.”Abdu! Rahim said he lost conscience sometime at night and woke up to find a soldier pulling him from the leg. He told the soldier to stop dragging him along with the dead bodies. “The soldier took out his gun and was about to shoot me when an ambulance arrived and its driver asked if the soldiers had any wounded. It was my lucky minute. The driver put me in his ambulance and drove to the hospital.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/1/

1-Jamal Freij was 17 years old the day the massacre took place. He was among a number of villagers working their fields. Among their group, there were some 25 girls and women. “Two kids from the village came to notify us that curfew hour was moved earlier to five in the afternoon. I told the women to head back to their homes. I went, along with a number of men, to a warehouse to change our clothes.

On our way back, and at a distance of two kilometers, we heard heavy shooting coming from the village direction. We started to retreat but a lorry driver who came rushing towards the village told us there was no need to run away simply because, he thought and we believed, the shooting was not that serious or indiscriminate. At the entrance to the village, three soldiers stopped us.

Their officer ordered us to get out of the lorry, which drove us to the village. The minute we told him we all were from Kufr Qassem he ordered his soldiers to open fire. They shot at us. Many fell on the ground, dead or wounded. I was among a number of men who ran away but I fell a minute later and hid myself behind the lorry’s wheel until the soldiers discovered me late at night and took me back to the village.”

2-Talal Issa Shaker was eight years only. Villagers still remember the tragedy that involved his death. He went out to return the flock of sheep from the neighboring fields. A villager I met confirmed that the soldiers “saw Talal and shot him dead. When his father went out to check what was happening, they soldiers shot and seriously wounded him. The mother later went out and was shot and so was the daughter, Noura.”

3-Mustafa Khamis Amer is now 58 years old. He explains how he miraculously escaped death: “The soldiers at the southern entrance to the village stopped us and checked our identity cards. Immediately afterwards, their officer ordered them to shoot. I started to run away and managed to disappear from them while many others were shot dead or wounded.” On that day, Mustafa added, villagers from nearby Jaijoulya were brought in by the army to dig a huge hole, which at the time they never knew it was meant to become the collective grave for the victims. All bodies were put in nylon bags and put aside ready for burial, he said.

4-Saleh Khalil Issa was 19 years old. His testimony, given in detail to Latif Dori three days after the massacre, gave the following account: “We were heading back to the village on our bicycles. We arrived at about ten to five in the afternoon. Three soldiers at the western entrance to the village ordered us to stop. Each of us put his hand in his pocket to pull out his identity card but the officer did not wait. He gave orders to open fire. They shot and immediately killed my cousin Abed Salim Issa and injured his brother Asaad and myself. We fell on the ground and then we saw another group of people riding their bicycles approaching. They were a group of eleven people, whose names are known to me. I heard the officer giving orders using a term HARVEST THEM and they opened fire. We fell on the ground.

I saw a car approaching driven by Ata Yaacob who had some passengers with him. They all were ordered to step out of the car and to stand in a queue. The officer again used the same term and fire was opened at them. The soldiers then pulled all bodies to a nearby field. At a certain moment, we found out the soldiers were looking in the opposite direction and we started to run away. We ran for some 50 metres and fire was shot at us again. I took the ground and stayed there until the next morning. Throughout the night, I heard soldiers giving instructions to move the bodies. In the morning, the soldiers saw me and took me to the hospital.

5-Abdul Rahim Sarsour was also 17 years old on that day. He remembers how he was injured on his way back to the village when soldiers opened fire at him and at the group that returned with him. He pretended he was dead to escape being shot at again by the soldiers. He said he still feels guilty for the death of his brother, whom their mother sent to inform Abdul Rahim and the others that the curfew hour was changed. “Had he stayed home, he would be alive today,”said Abdul Rahim who gave the following account: “We arrived in the village. Soldiers were manning a roadblock on the entrance. They ordered us out of the car.

An officer then gave his orders to HARVEST US and fire was opened indiscriminately in our direction. I fell on the ground and so did many others, some were killed immediately and others wounded. My brother fell next to me. He murmured asking if I was hit. I gave him a blow with my elbow to remain silent but it was too late. A soldier approached and fired four bullets at me, hitting both my right leg and arm. The soldier then pointed his gun to my brother’s head and fired several rounds of bullets. The head exploded in pieces while I was watching but did not dare say a single word.

I cannot forget that moment at all. I still remember how my brother, frightened by the soldiers, was pressing with his hands on my chest. When the soldier fire at him, I felt the pressure increasing for a second or two until his hands went loose. Jum’ah Sarsour, another wounded. lay next to me. He was moaning with pain. I tried to ask him to remain silent but it was too late too. One of the soldiers drew close to him and shot him dead. A third main badly wounded was screaming at the soldiers. A soldier approached him and shouted WHY ARE YOU SHOUTING, YOU SON-OF-A-BITCH and shot him dead.

A car approached with a number of women aboard singing. One of the girls saw the bodies and yelled on the rest to stop singing. The driver sped away from the scene but some 150 meters away we heard plenty of shooting.”Abdu! Rahim said he lost conscience sometime at night and woke up to find a soldier pulling him from the leg. He told the soldier to stop dragging him along with the dead bodies. “The soldier took out his gun and was about to shoot me when an ambulance arrived and its driver asked if the soldiers had any wounded. It was my lucky minute. The driver put me in his ambulance and drove to the hospital.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/1/

“One of the most horrible massacres committed in cold blood against innocent and defenseless civilians took place in Kafr Qasem on the eve of the assault against Egypt. It was intended to cause panic and trigger flight across the borders in a replicate to what happened in 1948 when the massacre of Deir Yassin was committed while Plan Dalet was taking place. The innocent victims, including women and children, were farmers coming back from the field not aware that a curfew had been imposed on their village and neighboring Arab communities.

The curfew was declared at 4:30 P.M. to take force at 5:00 P.M. Explicit orders were given to the soldiers “to shoot to kill all who broke the curfew…there shall be no arrests”. Hadashot established that the slaughter was carried out against the background of a plan devised by the Israeli army on the eve of the 1956 war – Hafarferet. It was intended to create panic and cause the inhabitants of the area to flee across the borders. A Border Guard battalion of the IDF carried out the massacre.

Major Shmuel Malinki and Lieutenant Gabriel Dahan were found guilty of the killings and sentenced to 17 and 15 years respectively. The punishment did not fit the crime. Nevertheless, the convicted men were pardoned and released from prison within 3 years from the massacre.

The Jewish Agency gave Dahan a job as manager of the sale of Israel’s government bonds in a European capital. Malinki, who was stripped of his rank by the court, was reinstated by Ben-Gurion. Malinki’s widow, Nehama, revealed many years later that while the trial was in progress her husband was released from prison to meet Ben-Gurion who told him that he was a “living victim of the state”, and pleaded with him not to reveal orders he was given by his superiors lest this implicate the cabinet and the general staff, and that he was promised an early release and reinstatement. The PM offered Malinki a very important post: security officer of the new, top secret nuclear plant at Dimona, in the Negev.

Malinki talked about a message he had received from Ben-Gurion, in which he had been requested to maintain silence in return for being granted a pardon. In spite of the special treatment he had received, Malinki remained until his death in 1978 very bitter at the fact of having been brought to trial in the first place and having been made a scapegoat for the state’s plans toward the Israeli Arabs. The attack against Egypt was also exploited to carry out another mass expulsion of Israeli Arabs across the northern border into Syria. This episode, involving the expulsion of 2,000 – 5,000 inhabitants of the two villages Krad al-Ghannamah and Krad al-Baqqarah, to the south of Lake Hulah, was revealed by Yitzhak Rabin in his “Service Notebook”. Rabin was the Commanding Officer of the Northern Command at the time.” http://cosmos.ucc.ie/cs1064/jabowen/IPSC/php/event.php?eid=149

“This most infamous massacre was perpetrated by the Israeli military in execution of the most dramatic expulsion plan of ‘Israeli Arabs’, the secret ‘Operation Hafarferet’. The essence of this secret plan, revealed for the first time on 25 October 1991 by the Hebrew newspaper Hadashot, was to expel the Arab inhabitants of the ‘Little Triangle’ (over 40,000 Israeli Arab citizens), apparently to Jordan. Hadashot established that the slaughter was carried out against the background of military plan devised by the Israeli army on the eve of the 1956 war.

On 29 October 1956, the day the Israeli army launched its attack on Egypt in the south, the Israeli Border Police carried out a large massacre in the Israeli Arab village of Kafr Qassim, in the Little Triangle bordering the West Bank. Ostensibly, the cause of this extensively documented massacre was the breaking of a curfew by the victims, who were not aware that a curfew had been imposed on their village and neighbouring Arab communities.

The battalion [brigade] commander in charge of imposing the curfew [Shadmi] told the unit commander [Malinki] that the curfew must be extremely strict. When Malinki asked what was to happen to a man returning from his work outside the village, without knowing about the curfew, who might well meet the Border Police units at the entrance to the village, Shadmi replied: “I don’t want any sentimentality” and “That’s just too bad for him.” Only 30 minutes separated the announcement of the curfew from its harsh enforcement, and the villagers deliberately had been given no cause for the treatment they received. Within an hour of the curfew, between 5 and 6 P.M., 47 villagers returning from work were killed. The 43 killed at the western entrance of Kafr Qassim included seven boys and girls and nine women between the ages of 18 and 61.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/7/

The curfew was declared at 4:30 P.M. to take force at 5:00 P.M. Explicit orders were given to the soldiers “to shoot to kill all who broke the curfew…there shall be no arrests”. Hadashot established that the slaughter was carried out against the background of a plan devised by the Israeli army on the eve of the 1956 war – Hafarferet. It was intended to create panic and cause the inhabitants of the area to flee across the borders. A Border Guard battalion of the IDF carried out the massacre.

Major Shmuel Malinki and Lieutenant Gabriel Dahan were found guilty of the killings and sentenced to 17 and 15 years respectively. The punishment did not fit the crime. Nevertheless, the convicted men were pardoned and released from prison within 3 years from the massacre.

The Jewish Agency gave Dahan a job as manager of the sale of Israel’s government bonds in a European capital. Malinki, who was stripped of his rank by the court, was reinstated by Ben-Gurion. Malinki’s widow, Nehama, revealed many years later that while the trial was in progress her husband was released from prison to meet Ben-Gurion who told him that he was a “living victim of the state”, and pleaded with him not to reveal orders he was given by his superiors lest this implicate the cabinet and the general staff, and that he was promised an early release and reinstatement. The PM offered Malinki a very important post: security officer of the new, top secret nuclear plant at Dimona, in the Negev.

Malinki talked about a message he had received from Ben-Gurion, in which he had been requested to maintain silence in return for being granted a pardon. In spite of the special treatment he had received, Malinki remained until his death in 1978 very bitter at the fact of having been brought to trial in the first place and having been made a scapegoat for the state’s plans toward the Israeli Arabs. The attack against Egypt was also exploited to carry out another mass expulsion of Israeli Arabs across the northern border into Syria. This episode, involving the expulsion of 2,000 – 5,000 inhabitants of the two villages Krad al-Ghannamah and Krad al-Baqqarah, to the south of Lake Hulah, was revealed by Yitzhak Rabin in his “Service Notebook”. Rabin was the Commanding Officer of the Northern Command at the time.” http://cosmos.ucc.ie/cs1064/jabowen/IPSC/php/event.php?eid=149

“This most infamous massacre was perpetrated by the Israeli military in execution of the most dramatic expulsion plan of ‘Israeli Arabs’, the secret ‘Operation Hafarferet’. The essence of this secret plan, revealed for the first time on 25 October 1991 by the Hebrew newspaper Hadashot, was to expel the Arab inhabitants of the ‘Little Triangle’ (over 40,000 Israeli Arab citizens), apparently to Jordan. Hadashot established that the slaughter was carried out against the background of military plan devised by the Israeli army on the eve of the 1956 war.

On 29 October 1956, the day the Israeli army launched its attack on Egypt in the south, the Israeli Border Police carried out a large massacre in the Israeli Arab village of Kafr Qassim, in the Little Triangle bordering the West Bank. Ostensibly, the cause of this extensively documented massacre was the breaking of a curfew by the victims, who were not aware that a curfew had been imposed on their village and neighbouring Arab communities.

The battalion [brigade] commander in charge of imposing the curfew [Shadmi] told the unit commander [Malinki] that the curfew must be extremely strict. When Malinki asked what was to happen to a man returning from his work outside the village, without knowing about the curfew, who might well meet the Border Police units at the entrance to the village, Shadmi replied: “I don’t want any sentimentality” and “That’s just too bad for him.” Only 30 minutes separated the announcement of the curfew from its harsh enforcement, and the villagers deliberately had been given no cause for the treatment they received. Within an hour of the curfew, between 5 and 6 P.M., 47 villagers returning from work were killed. The 43 killed at the western entrance of Kafr Qassim included seven boys and girls and nine women between the ages of 18 and 61.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/7/

“At first, the whole affair was kept strictly concealed from the public eye by the sharp censorship. However, a young Israeli journalist, fluent in the Arabic language, Latif Dori, a correspondent of the organ of the United Workers’ Party Mapam, which at the time was a coalition partner in the Labor led Ben-Gurion Government, got wind of the horrible affair. He succeeded to enter Kufr-Qassem illegally in spite of the curfew a few days after the event.

At a press conference, held last week in Tel-Aviv by the Arab-Jewish Solidarity Committee with Kufr-Qassem towards the 40th anniversary, Dori stressed that the reports, he at the time heard in the village, made his hair stand on end. He tried to mobilize leading figures from his party, among them cabinet ministers and Knesset members, but these rejected any attempt to break the plot of hushing up the crime. Dori then turned to two communist Knesset members, Tawfiq Toubi and Meir Vilner.

Together with Dori they visited the wounded survivors, kept under close police detention in a Jewish hospital near Petah-Tiqva and listened to their eyewitness reports. MKs Toubi and Vilner turned to the then PM and Defense Minister Ben-Gurion, as well as to the Knesset Presidium to protest and to raise the matter in the Knesset with the intention to set up a neutral public investigation committee, as well as demanding that the officers, responsible for the massacre be put on trial.

When Ben-Gurion and the Knesset bodies refused to act, the communist Knesset members published a pamphlet, relating the blood-curling story of the massacre together with all those eyewitness reports, they heard in the Beilinson hospital. The pamphlet was sent to several thousand personalities, politicians, academics, journalists and trade union leaders. Uri Avneri, then the publisher and editor of the weekly magazine “Olam Haze” popular mainly among the younger generation, today the leading figure in the Gush-Shalom peace bloc, broke the censorship and published the whole story. With this, the taboo about the Kufr-Qassem blood bath was lifted. The government was forced by the public uproar about the affair to bring charges before a military court against the army officers and NCOs responsible for the crime.

In the verdict, convicting the perpetrators of the Kufr-Qassem massacre, District Judge Benjamin Halevy, inter alia ruled, that the claim of having acted according to commands given by their superior officers, should not have been executed, but rejected. He pointed to the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, as well as to some of the trials against Nazi S.S. murderers, who tried to excuse their bloody crimes committed against Jews, Gypsies and political opponents of the Nazi regime by “only having executed commands by their superiors”. “Such claims for clemency cannot be accepted by any court of justice in the Jewish State of Israel” judge Benjamin Halevy ruled.

Officers and men of the army and other security forces have not only the right, but even the duty to refuse executing commands which represent offenses against human rights and the legal code of the state, the judge stated in his verdict. This ruling was adopted by the Supreme Court and is still in force in the Israeli juridical code. (The Yesh-Gvul army reservists, who refuse to do reserve duties in the occupied territories, regularly call upon the personnel of the army and police forces stationed in the occupied Palestinian territories, to refuse commands, representing illegal acts according to this ruling).

Eleven of the murderers were sentenced to prison terms of 5 to 17 years. But they never have seen a jail from inside. They did their time in a comfortable hotel in Jerusalem. And then, by way of several mitigations, and at the end of being pardoned by the upper military echelon and the then President of Israel, some of them were released soon after, and not one of them spent more than three years in jail. Moreover, the main culprit, Major Malinki, after his having been pardoned and released from jail, was appointed to be the director general of the Dimona Atom reactor, in which, as known today, Israel produces nuclear war devices. The second next in command of the killing squad, Lieutenant Dahan, was later appointed to be the “civil commander” responsible for the Arab minority population of the town Ramle not far from Kufr-Qassem.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/4/

At a press conference, held last week in Tel-Aviv by the Arab-Jewish Solidarity Committee with Kufr-Qassem towards the 40th anniversary, Dori stressed that the reports, he at the time heard in the village, made his hair stand on end. He tried to mobilize leading figures from his party, among them cabinet ministers and Knesset members, but these rejected any attempt to break the plot of hushing up the crime. Dori then turned to two communist Knesset members, Tawfiq Toubi and Meir Vilner.

Together with Dori they visited the wounded survivors, kept under close police detention in a Jewish hospital near Petah-Tiqva and listened to their eyewitness reports. MKs Toubi and Vilner turned to the then PM and Defense Minister Ben-Gurion, as well as to the Knesset Presidium to protest and to raise the matter in the Knesset with the intention to set up a neutral public investigation committee, as well as demanding that the officers, responsible for the massacre be put on trial.

When Ben-Gurion and the Knesset bodies refused to act, the communist Knesset members published a pamphlet, relating the blood-curling story of the massacre together with all those eyewitness reports, they heard in the Beilinson hospital. The pamphlet was sent to several thousand personalities, politicians, academics, journalists and trade union leaders. Uri Avneri, then the publisher and editor of the weekly magazine “Olam Haze” popular mainly among the younger generation, today the leading figure in the Gush-Shalom peace bloc, broke the censorship and published the whole story. With this, the taboo about the Kufr-Qassem blood bath was lifted. The government was forced by the public uproar about the affair to bring charges before a military court against the army officers and NCOs responsible for the crime.

In the verdict, convicting the perpetrators of the Kufr-Qassem massacre, District Judge Benjamin Halevy, inter alia ruled, that the claim of having acted according to commands given by their superior officers, should not have been executed, but rejected. He pointed to the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, as well as to some of the trials against Nazi S.S. murderers, who tried to excuse their bloody crimes committed against Jews, Gypsies and political opponents of the Nazi regime by “only having executed commands by their superiors”. “Such claims for clemency cannot be accepted by any court of justice in the Jewish State of Israel” judge Benjamin Halevy ruled.

Officers and men of the army and other security forces have not only the right, but even the duty to refuse executing commands which represent offenses against human rights and the legal code of the state, the judge stated in his verdict. This ruling was adopted by the Supreme Court and is still in force in the Israeli juridical code. (The Yesh-Gvul army reservists, who refuse to do reserve duties in the occupied territories, regularly call upon the personnel of the army and police forces stationed in the occupied Palestinian territories, to refuse commands, representing illegal acts according to this ruling).

Eleven of the murderers were sentenced to prison terms of 5 to 17 years. But they never have seen a jail from inside. They did their time in a comfortable hotel in Jerusalem. And then, by way of several mitigations, and at the end of being pardoned by the upper military echelon and the then President of Israel, some of them were released soon after, and not one of them spent more than three years in jail. Moreover, the main culprit, Major Malinki, after his having been pardoned and released from jail, was appointed to be the director general of the Dimona Atom reactor, in which, as known today, Israel produces nuclear war devices. The second next in command of the killing squad, Lieutenant Dahan, was later appointed to be the “civil commander” responsible for the Arab minority population of the town Ramle not far from Kufr-Qassem.” http://www.kufur-kassem.com/cms/content/view/148/154/1/4/