28 nov 2001

A Belgian court will today decide whether to try Ariel Sharon for war crimes. Julie Flint uncovers secret documents that detail Israel's involvement in the 1982 massacres at Sabra and Shatila

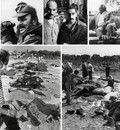

It is September 19 1982, the day after the Lebanese Forces militia left Beirut's Palestinian camps after a 38-hour orgy of killing, and it is finally possible to see what the Israeli soldiers surrounding the camps claimed they had been unable to see. Streets carpeted with bodies. Men, women and children shot and hacked to death. Pregnant women eviscerated.

In Christian East Beirut, Israel's chief of staff, Lieutenant General Rafael Eitan, the commander of the Northern District, Major General Amir Drori, and a senior Mossad officer, Menahem Navot, codenamed Mr R, meet the deputy chief of staff of the Lebanese Forces, Antoine Breidi - "Toto" - and Joseph abu Khalil, the man who made the first contact with the Israelis in March 1976.

What ensues is a cynical damage-limitation conference in which senior officers of the Israeli Defence Forces utter not one word of reproach for a massacre in which mili tiamen trained, armed and sent into the camps by them killed at least 900 defenceless civilians. Gen Eitan: "Everybody points an accusing finger at Israel and the outcome might be that the IDF will be forced to withdraw from Beirut. Therefore some of you have to explain the subject and immediately. The formula should be that they [the Lebanese Forces] took part in an assignment and that whatever occurred was out of their control."

Gen Drori: "On this occasion you should mention also what happened at Damour [a Christian village where fighters including Palestinians killed 200 civilians in 1976]. Also to mention the fact that this is not your policy. You could mention that in the places that they entered there were battles between rival sides inside the camps and not only with the Phalangists [the LF's political umbrella]."

Abu Khalil: "... You tell us and we will carry it out."

And so it goes on - a web of evasions and untruths concocted by the IDF, which sent 200 Lebanese militiamen into Sabra and Shatila on September 16 to "mop up" 2,000 "terrorists" who Ariel Sharon, then Israel's defence minister, claimed had remained there after the PLO's evacuation from Beirut. It is an encounter that shows the intimacy between the IDF and the LF, even after the massacre, and the virtual incorporation of the LF into the IDF structure.

Two almost identical reports of this meeting - one identified as "a transcript of a conversation recorded by an aide to the commander of the Northern District"; the other as "Minutes of Mossad (4222) of a meeting between Israeli chief of staff and Gen Drori with Toto" - are among a stack of documents delivered to lawyers seeking to bring Sharon, now Israel's prime minister, to trial in Belgium for war crimes committed in Lebanon 19 years ago when he had overall responsibility for the IDF.

The documents, exclusively obtained by the Guardian, cover the period between June and November 1982 - from a meeting in which "the cabinet has decided to have the Lebanese army and the Phalangists participate in the entering of Beirut" to the testimony to Israel's Kahan commission of inquiry of a senior military intelligence officer, Colonel Elkana Harnof. Some are in Hebrew; others in English. Michael Verhaeghe, one of three lawyers representing the plaintiffs in the case against Sharon, has little doubt about the documents' authenticity. They arrived anonymously in June, within 10 days of the suit being lodged under legislation that allows Belgium to prosecute foreigners for war crimes, wherever they were committed.

"The documents give a very detailed account of a number of events which would be very difficult to fabricate - especially in that very short period of time," says Verhaeghe. Investigations by the Guardian in Israel and Lebanon have confirmed the identity of the intelligence officers named in the documents as well as the dates, times and locations of some of the meetings, those who attended them and some of their content. The typescript of the Hebrew documents matches that used at the time of Kahan. And the voices of many of the protagonists are unmistakable - among them the courtly Pierre Gemayel, patriarch of the Gemayel family, and Sharon, referred to throughout as DM.

Thus, from minutes of a meeting on August 21 at Gemayel's home in Bikfaya: Pierre: "I visited Israel several times. I was very impressed." DM: "How to create power and how to convey its presence is the great test. We were 18 million, six million were exterminated... The use of power is what I want to discuss with you."

The lawyers say the documents' importance lies in recurring evidence that the IDF had "command responsibility" for the Lebanese Forces before, during and after the massacre. Thus, according to a summary of a meeting in which "the capture of Beirut" was discussed with LF leaders on July 13, Gen Eitan "explained that the IDF would provide all the necessary support: artillery, air etc as if they were regular IDF units".

"Under the established law of command responsibility - also known as indirect responsibility - this is watertight evidence of the conscious and effective chain of command," says Chibli Mallat, one of Verhaeghe's colleagues.

In February 1983, the Kahan commission found that no Israeli was "directly responsible" for the massacre, but determined that Sharon bore "personal responsibility". It ruled that he was negligent in ignoring the possibility of bloodshed in the camps following the assassination of the Lebanese Forces' leader, president-elect Bashir Gemayel, on September 14 - a massacre that Sharon publicly, and erroneously, blamed on Palestinians. Sharon resigned his defence portfolio, but stayed in the cabinet.

In Brussels today an appeals court will meet in closed session to decide whether to put Israel's prime minister on trial. Sharon's lawyers will argue that he has immunity as a head of government; that he is a victim of double jeopardy after the Kahan inquiry; and that the Belgian law cannot be used retroactively - claims that Mallat and his colleagues dismiss. Only if the appeals court rules for the plaintiffs will the documents be introduced to a court, obliging Sharon's lawyers either to acknowledge them or to produce others that refute them. Only then will a court hear of Sharon's early insistence that the Lebanese Forces "clean" the camps, despite their known proclivity for murder and rape.

Thus, even as the first PLO fighters left Beirut on August 21, Sharon met Bashir and Pierre Gemayel to demand a new strike against the Palestinian presence in Lebanon. Minutes of the meeting quote Sharon as saying: "A question was raised before, what would happen to the Palestinian camps once the terrorists withdraw... You've got to act... So that there be no terrorists you've got to clean the camps." Pierre Gemayel prevaricated: "We are in the midst of a political process of presidential elections... Bashir is the nominee... It is very important that calm is kept." Sharon insisted: "What would you do about the camps?" Bashir: "We are planning a real zoo."

In his testimony to Kahan, Sharon claimed that no one imagined the Lebanese Forces would carry out a massacre in the camps. This claim is contradicted by numerous testimonies in the documents in Belgium - among them Sharon's own complaint to Bashir Gemayel, minuted 10 weeks before the massacre, that "it is incumbent that we prevent several ugly things which have occurred - murders, rapes and stealing by some of your men". In the same month, in a meeting with American diplomats at the home of Johnny Abdo, Lebanon's military intelligence chief, Sharon proposed that the PLO fighters in Beirut be given "refuge" in Israel. "Although we are at a friend's house," he said, according to the report of the meeting, "rest assured that they would be more secure in our hands!"

Verhaeghe's documents show that this belief was shared by top intelligence officials identified in a secret part of the Kahan report - Appendix B. Kahan said Appendix B would not be published for reasons of national security. The lawyers believe the documents referring to these officers must come from Appendix B, but do not know whether the entire file is from Appendix B.

Echoing Sharon's concerns, according to excerpts from testimony to Kahan on October 22, Mossad chief Yitzhak Hoffi says the Phalangists "talk about solving the Palestinian problem with a hand gesture whose meaning is physical elimination... I don't think anybody had any doubts about this... They raised the issue of Lebanon being unable to survive as long as this size of population existed there." Similarly, Col Harnof, in a summary of his testimony a month later: "It was possible to surmise from contacts with the Phalange leaders what were their intentions towards the Palestinians: 'Sabra would become a zoo and Shatila Beirut's parking place' ... When they participated in actions east of Bahamdoun [when they operated against the Druze] they ran straight to the villages and committed massacres."

But the clearest indication of how the Lebanese Forces might solve the "demographic problem" was given by Bashir Gemayel himself in a meeting with Menachem Navot. In one account of this meeting, Bashir "adds that it is possible that in this context they will need several Dir Yassins" - a reference to the Palestinian village where 254 villagers were massacred in April 1948, in the most spectacular single attack in the conquest of Palestine.

In June this year, the first case involving the exercise of universal jurisdiction in Belgium resulted in the conviction of four Rwandans for war crimes committed in 1994. Mallat and his colleagues say they are determined to press for a similar result despite the accusations being levelled against them - among them anti-semitism, animosity and hatred. They say their starting point is not the criminal but the crime.

"I have a very profound belief that it is difficult to have peace in the Middle East without minimal accountability, certainly for the largest crimes," says Mallat. "We need a day of reckoning for the outstanding crime against humanity committed in Sabra and Shatila."

It is September 19 1982, the day after the Lebanese Forces militia left Beirut's Palestinian camps after a 38-hour orgy of killing, and it is finally possible to see what the Israeli soldiers surrounding the camps claimed they had been unable to see. Streets carpeted with bodies. Men, women and children shot and hacked to death. Pregnant women eviscerated.

In Christian East Beirut, Israel's chief of staff, Lieutenant General Rafael Eitan, the commander of the Northern District, Major General Amir Drori, and a senior Mossad officer, Menahem Navot, codenamed Mr R, meet the deputy chief of staff of the Lebanese Forces, Antoine Breidi - "Toto" - and Joseph abu Khalil, the man who made the first contact with the Israelis in March 1976.

What ensues is a cynical damage-limitation conference in which senior officers of the Israeli Defence Forces utter not one word of reproach for a massacre in which mili tiamen trained, armed and sent into the camps by them killed at least 900 defenceless civilians. Gen Eitan: "Everybody points an accusing finger at Israel and the outcome might be that the IDF will be forced to withdraw from Beirut. Therefore some of you have to explain the subject and immediately. The formula should be that they [the Lebanese Forces] took part in an assignment and that whatever occurred was out of their control."

Gen Drori: "On this occasion you should mention also what happened at Damour [a Christian village where fighters including Palestinians killed 200 civilians in 1976]. Also to mention the fact that this is not your policy. You could mention that in the places that they entered there were battles between rival sides inside the camps and not only with the Phalangists [the LF's political umbrella]."

Abu Khalil: "... You tell us and we will carry it out."

And so it goes on - a web of evasions and untruths concocted by the IDF, which sent 200 Lebanese militiamen into Sabra and Shatila on September 16 to "mop up" 2,000 "terrorists" who Ariel Sharon, then Israel's defence minister, claimed had remained there after the PLO's evacuation from Beirut. It is an encounter that shows the intimacy between the IDF and the LF, even after the massacre, and the virtual incorporation of the LF into the IDF structure.

Two almost identical reports of this meeting - one identified as "a transcript of a conversation recorded by an aide to the commander of the Northern District"; the other as "Minutes of Mossad (4222) of a meeting between Israeli chief of staff and Gen Drori with Toto" - are among a stack of documents delivered to lawyers seeking to bring Sharon, now Israel's prime minister, to trial in Belgium for war crimes committed in Lebanon 19 years ago when he had overall responsibility for the IDF.

The documents, exclusively obtained by the Guardian, cover the period between June and November 1982 - from a meeting in which "the cabinet has decided to have the Lebanese army and the Phalangists participate in the entering of Beirut" to the testimony to Israel's Kahan commission of inquiry of a senior military intelligence officer, Colonel Elkana Harnof. Some are in Hebrew; others in English. Michael Verhaeghe, one of three lawyers representing the plaintiffs in the case against Sharon, has little doubt about the documents' authenticity. They arrived anonymously in June, within 10 days of the suit being lodged under legislation that allows Belgium to prosecute foreigners for war crimes, wherever they were committed.

"The documents give a very detailed account of a number of events which would be very difficult to fabricate - especially in that very short period of time," says Verhaeghe. Investigations by the Guardian in Israel and Lebanon have confirmed the identity of the intelligence officers named in the documents as well as the dates, times and locations of some of the meetings, those who attended them and some of their content. The typescript of the Hebrew documents matches that used at the time of Kahan. And the voices of many of the protagonists are unmistakable - among them the courtly Pierre Gemayel, patriarch of the Gemayel family, and Sharon, referred to throughout as DM.

Thus, from minutes of a meeting on August 21 at Gemayel's home in Bikfaya: Pierre: "I visited Israel several times. I was very impressed." DM: "How to create power and how to convey its presence is the great test. We were 18 million, six million were exterminated... The use of power is what I want to discuss with you."

The lawyers say the documents' importance lies in recurring evidence that the IDF had "command responsibility" for the Lebanese Forces before, during and after the massacre. Thus, according to a summary of a meeting in which "the capture of Beirut" was discussed with LF leaders on July 13, Gen Eitan "explained that the IDF would provide all the necessary support: artillery, air etc as if they were regular IDF units".

"Under the established law of command responsibility - also known as indirect responsibility - this is watertight evidence of the conscious and effective chain of command," says Chibli Mallat, one of Verhaeghe's colleagues.

In February 1983, the Kahan commission found that no Israeli was "directly responsible" for the massacre, but determined that Sharon bore "personal responsibility". It ruled that he was negligent in ignoring the possibility of bloodshed in the camps following the assassination of the Lebanese Forces' leader, president-elect Bashir Gemayel, on September 14 - a massacre that Sharon publicly, and erroneously, blamed on Palestinians. Sharon resigned his defence portfolio, but stayed in the cabinet.

In Brussels today an appeals court will meet in closed session to decide whether to put Israel's prime minister on trial. Sharon's lawyers will argue that he has immunity as a head of government; that he is a victim of double jeopardy after the Kahan inquiry; and that the Belgian law cannot be used retroactively - claims that Mallat and his colleagues dismiss. Only if the appeals court rules for the plaintiffs will the documents be introduced to a court, obliging Sharon's lawyers either to acknowledge them or to produce others that refute them. Only then will a court hear of Sharon's early insistence that the Lebanese Forces "clean" the camps, despite their known proclivity for murder and rape.

Thus, even as the first PLO fighters left Beirut on August 21, Sharon met Bashir and Pierre Gemayel to demand a new strike against the Palestinian presence in Lebanon. Minutes of the meeting quote Sharon as saying: "A question was raised before, what would happen to the Palestinian camps once the terrorists withdraw... You've got to act... So that there be no terrorists you've got to clean the camps." Pierre Gemayel prevaricated: "We are in the midst of a political process of presidential elections... Bashir is the nominee... It is very important that calm is kept." Sharon insisted: "What would you do about the camps?" Bashir: "We are planning a real zoo."

In his testimony to Kahan, Sharon claimed that no one imagined the Lebanese Forces would carry out a massacre in the camps. This claim is contradicted by numerous testimonies in the documents in Belgium - among them Sharon's own complaint to Bashir Gemayel, minuted 10 weeks before the massacre, that "it is incumbent that we prevent several ugly things which have occurred - murders, rapes and stealing by some of your men". In the same month, in a meeting with American diplomats at the home of Johnny Abdo, Lebanon's military intelligence chief, Sharon proposed that the PLO fighters in Beirut be given "refuge" in Israel. "Although we are at a friend's house," he said, according to the report of the meeting, "rest assured that they would be more secure in our hands!"

Verhaeghe's documents show that this belief was shared by top intelligence officials identified in a secret part of the Kahan report - Appendix B. Kahan said Appendix B would not be published for reasons of national security. The lawyers believe the documents referring to these officers must come from Appendix B, but do not know whether the entire file is from Appendix B.

Echoing Sharon's concerns, according to excerpts from testimony to Kahan on October 22, Mossad chief Yitzhak Hoffi says the Phalangists "talk about solving the Palestinian problem with a hand gesture whose meaning is physical elimination... I don't think anybody had any doubts about this... They raised the issue of Lebanon being unable to survive as long as this size of population existed there." Similarly, Col Harnof, in a summary of his testimony a month later: "It was possible to surmise from contacts with the Phalange leaders what were their intentions towards the Palestinians: 'Sabra would become a zoo and Shatila Beirut's parking place' ... When they participated in actions east of Bahamdoun [when they operated against the Druze] they ran straight to the villages and committed massacres."

But the clearest indication of how the Lebanese Forces might solve the "demographic problem" was given by Bashir Gemayel himself in a meeting with Menachem Navot. In one account of this meeting, Bashir "adds that it is possible that in this context they will need several Dir Yassins" - a reference to the Palestinian village where 254 villagers were massacred in April 1948, in the most spectacular single attack in the conquest of Palestine.

In June this year, the first case involving the exercise of universal jurisdiction in Belgium resulted in the conviction of four Rwandans for war crimes committed in 1994. Mallat and his colleagues say they are determined to press for a similar result despite the accusations being levelled against them - among them anti-semitism, animosity and hatred. They say their starting point is not the criminal but the crime.

"I have a very profound belief that it is difficult to have peace in the Middle East without minimal accountability, certainly for the largest crimes," says Mallat. "We need a day of reckoning for the outstanding crime against humanity committed in Sabra and Shatila."

27 july 2001

Israel reveals its fear of war crimes trials

The Israeli contingency plan follows reports yesterday that Tel Aviv has hired a Belgian lawyer for Mr Sharon, who will try to persuade judges in Brussels to throw out a complaint seeking his prosecution over the massacre of Palestinian refugees nearly 20 years ago.

The Belgian courts are also reportedly considering complaints against Israel's army chief, Shaul Mofaz, and the air force commander, Dan Halutz, for the death of Palestinian civilians during the current 10-month-old uprising.

Israel reveals its fear of war crimes trials

The Israeli contingency plan follows reports yesterday that Tel Aviv has hired a Belgian lawyer for Mr Sharon, who will try to persuade judges in Brussels to throw out a complaint seeking his prosecution over the massacre of Palestinian refugees nearly 20 years ago.

The Belgian courts are also reportedly considering complaints against Israel's army chief, Shaul Mofaz, and the air force commander, Dan Halutz, for the death of Palestinian civilians during the current 10-month-old uprising.

19 june 2001

Massacre survivors seek trial of Sharon in Belgium

Twenty-eight survivors of the Sabra and Shatila massacres in Beirut 19 years ago lodged an official complaint against the Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, in Brussels yesterday, taking advantage of a 1993 law which allows Belgium to try foreign nationals for war crimes committed abroad.

254 villagers were massacred in April 1948, in the most spectacular single attack in the conquest of Palestine.

254 villagers were massacred in April 1948, in the most spectacular single attack in the conquest of Palestine.

6 feb 2001

Israeli military murdered over 2000 Palestinians in the camps

This is a place of filth and blood which will forever be associated with Ariel Sharon. In Israel today, he may well be elected prime minister. Then he will be master of the most powerful nation in the Middle East; he will travel to America, he will visit the White House and shake hands with President George W Bush. But for everyone who stood in the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps in Beirut on 18 September 1982, his name is synonymous with butchery; with bloated corpses and disembowelled women and dead babies, with rape and pillage and murder...

Even when I walk these fetid streets today, more than 18 years after what was – by Israel’s own definition of that much-misused phrase – the worst single act of terrorism in modern Middle East history, the ghosts haunt me still. Over there, on the side of the road leading to the Sabra mosque, lay Mr Nouri, 90 years old, grey-bearded, in pyjamas with a small woollen hat still on his head and a stick by his side. I found him on a pile of garbage, on his back, fly-encrusted eyes staring at the blazing sun. Just up the lane, I came across two women sitting upright with their brains blown out, next to a cooking pot and a dead horse. One of the women appeared to have had her stomach slit open. A few metres away, I discovered the first babies, already black with decomposition, scattered across the road like rubbish.

This is a place of filth and blood which will forever be associated with Ariel Sharon. In Israel today, he may well be elected prime minister. Then he will be master of the most powerful nation in the Middle East; he will travel to America, he will visit the White House and shake hands with President George W Bush. But for everyone who stood in the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps in Beirut on 18 September 1982, his name is synonymous with butchery; with bloated corpses and disembowelled women and dead babies, with rape and pillage and murder...

Even when I walk these fetid streets today, more than 18 years after what was – by Israel’s own definition of that much-misused phrase – the worst single act of terrorism in modern Middle East history, the ghosts haunt me still. Over there, on the side of the road leading to the Sabra mosque, lay Mr Nouri, 90 years old, grey-bearded, in pyjamas with a small woollen hat still on his head and a stick by his side. I found him on a pile of garbage, on his back, fly-encrusted eyes staring at the blazing sun. Just up the lane, I came across two women sitting upright with their brains blown out, next to a cooking pot and a dead horse. One of the women appeared to have had her stomach slit open. A few metres away, I discovered the first babies, already black with decomposition, scattered across the road like rubbish.

Yes, those of us who got into Sabra and Chatila before the murderers left have our memories. The flies racing between the reeking bodies and our faces, between dried blood and reporter’s notebook, the hands of watches still ticking on dead wrists. I clambered up a rampart of earth – an abandoned bulldozer stood guiltily nearby – only to find, once I was atop the mound, that it swayed beneath me. And I looked down to find faces, elbows, mouths, a woman’s legs protruding through the soil. I had to hold on to these body parts to climb down the other side. Then there was the pretty girl, her head surrounded by a halo of clothes pegs, her blood still running from a hole in her back. We had burst into the yard of her home, desperate to avoid the Israeli-uniformed militiamen who still roamed the camp; coming in by back door, we had found her body as the murderers left by the front door.

And as I walked through the carnage on 18 September – the last day of the three-day massacre – with Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post, a fierce, tough, Colorado reporter, I remember how he stopped in shock and disgust. And then, with as much energy as his lungs could summon in the sweet, foul air, he shouted, “SHARON!” so loudly that the name echoed off the crumpled walls above the bodies. “He’s responsible for this fucking mess,” Jenkins roared. And that, just over four months later – in more diplomatic words and in a report in which the murderers were called “soldiers” – was what the Israeli commission of enquiry decided. Sharon, who was minister of defence, bore “personal responsibility”, the Kahan commission stated, and recommended his removal from office. Sharon resigned.

And as I walked through the carnage on 18 September – the last day of the three-day massacre – with Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post, a fierce, tough, Colorado reporter, I remember how he stopped in shock and disgust. And then, with as much energy as his lungs could summon in the sweet, foul air, he shouted, “SHARON!” so loudly that the name echoed off the crumpled walls above the bodies. “He’s responsible for this fucking mess,” Jenkins roared. And that, just over four months later – in more diplomatic words and in a report in which the murderers were called “soldiers” – was what the Israeli commission of enquiry decided. Sharon, who was minister of defence, bore “personal responsibility”, the Kahan commission stated, and recommended his removal from office. Sharon resigned.

And so today, in this fetid, awful place, where Lebanese Muslim militiamen were – three years later – to kill hundreds more Palestinians in a war which produced no official inquiries, where scarcely 20 per cent of the survivors still live, where brown mud and rubbish now covers the mass grave of 600 of the 1982 victims, the Palestinians wait to see if their tormentor will hold the highest office in the state of Israel.

“Ariel Sharon was responsible,” a well-dressed young man shouted at us from an apartment balcony yesterday morning. And who could disagree? Israel had invaded Lebanon on 6 June 1982 with a plan – known to Sharon but not vouchsafed to his Likud prime minister, Menachem Begin – to advance all the way to Beirut and surround Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organisation guerrillas in the Lebanese capital. Officially named “Operation Peace for Galilee” (the real Israeli military codename was “Snowball”), the invasion was supposedly a response to PLO rocket attacks across the Israeli border.

But the rocket attacks had followed a series of Israeli air-raids on Lebanon which had ended a UN-brokered ceasefire and which were supposedly in “retaliation” for the attempted murder of the Israeli ambassador to London – though his would-be killers came from the Abu Nidal group which had nothing to do with the PLO and hated Arafat. But Sharon had anyway received an earlier American “green light” for his operation from Alexander Haig in the spring of 1982. After two months and almost 17,000 deaths, most of them civilians – the majority killed by Israeli gunfire and air attack – the PLO withdrew from Beirut under international protection, leaving their unarmed families behind.

At which point Sharon announced that 2,000 “terrorists” remained in the Sabra and Chatila camps. These mythical “terrorists” prompted a small advance by Israeli tanks – contrary to an agreement with Washington – towards the Palestinian camps. A French UN officer who tried to photograph the advance was shot dead by an “unknown” sniper. Sharon repeated his extraordinary claim that “terrorists” remained in the camps. And it was then that the Christian Lebanese president-elect, Bashir Gemayel – the leader of the Phalange militia which had already murdered thousands of surrendering Palestinians in the Tel el-Zaatar camp in 1976 – was assassinated.

Sharon paid his condolences to Gemayel’s father, Pierre. He must have known the old man’s history. Pierre Gemayel had founded his party after being inspired by the Olympics in Nazi Germany in 1936 (“I liked their idea of order,” he once confided to me). Not for nothing did Israel’s militia allies use the fascist “Phalange” as their name. As the Christians prepared to bury their hero, Sharon – again contrary to assurances he had given the Americans – ordered the Israeli army into west Beirut to “restore order”.

The Israelis then asked the Christian Phalange – armed and uniformed by Israel and allied to Israel since 1976 – to enter the Israeli-surrounded camps to “liquidate” the “terrorists”. Which is why, on Thursday 16 September, guided by signposts which the Israelis had laid across a Beirut airport runway, the Christian gunmen walked through the southern entrance of Chatila, some of them drunk, a number on drugs – all under the eyes of the Israelis – and embarked on a war crime.

Today, much scarred by later wars, the lanes of Chatila still follow the same paths I walked down 18 years ago. There are always survivors who have never told their stories to us before. Yesterday I wandered up an alleyway – rippling with water pipes and running with rain and sewage – to find a middle-aged woman buying tomatoes from a stall. I was 30 metres from the road where I discovered Mr Nouri’s body almost two decades ago. She took me to her family home and introduced me to her daughter, Nadia Salameh. Nadia was only 12 when Ariel Sharon’s soldiers watched the Phalangist militia slaughter their way through the camps.

“At the end of this alleyway outside our home, we were all shocked by what we saw,” she told me, her voice slowly rising with the memory of horror. “I saw corpses there, seven deep, some decapitated, others with their throats slit. One of our neighbours was lying there, Um Ahmed Saad, and her body had grown big with the heat. Her hands had been chopped off at the wrists. She used to wear a lot of bracelets, a lot of gold. The Phalange obviously wanted the gold.”

Each house I enter contains the faded photographs of young men killed in the war, some by Israel’s allies, others by Shia Muslim gunmen in the later 1985 camps war. But their memories have not faded. Old Abdullah – he is 78 and pleaded with us not to use his family name – talks without looking at me, eyes staring at the wall. The ghosts are returning again. “The Phalange were led by Elie Hobeika,” he said, “but who sent them into the camps? The Israelis. And who was the defence minister? Sharon. They put their tanks round the camp. I was part of a delegation that tried to negotiate with them. We carried a white flag. When we got near, there was a man’s voice on a loudspeaker telling us to have our identity cards ready. But I didn’t have my ID. So I went back home. And it turned out the loudspeaker was being used by a Phalangist. And they murdered all the men in the delegation. I was the only one to survive.”

There was no doubt that the Israelis could see what the Lebanese Christian Phalange were doing. The Kahan commission was later to quote Lieutenant Avi Grabovski, deputy commander of an Israeli tank unit that was helping to encircle the camp: he watched the murder of five women and children and wanted to protest, but his battalion commander had replied to another soldier who complained that “we know, it’s not to our liking, and don’t interfere”. Up to 2,000 Palestinians were murdered – two mass graves remain unexhumed in Beirut – and Sharon’s reputation, already besmirched by the much earlier slaughter of more than 50 Palestinian civilians by his Commando Unit 101, seemed as buried as the Palestinian victims.

But like the garbage that has collected over the only known mass grave, the historical narrative – save for that of the survivors – has become overgrown. History moves on. Arafat recognised Israel and found himself trapped by an agreement that would give him neither a real “Palestine” nor secure the return of the refugees – including those in Sabra and Chatila – to what is now Israel. And the new leader of Israel is, within hours, likely to be the man who allowed the killers into the Beirut camps more than 18 years ago.

With power, of course, comes respect. CNN now calls Sharon “a barrel-framed veteran general who has built a reputation for flattening obstacles and reshaping Israel’s landscape”, while the BBC World Service on Sunday managed to avoid the fateful words Sabra and Chatila by referring only to his “chequered military career”. As for Nadia Salameh, “Sharon’s role here shows what he is capable of. If Sharon is elected, the whole peace process falls by the wayside because he doesn’t want peace.” It’s a relief to recall that up to a million Israelis demonstrated their moral integrity in 1982 by protesting in Tel Aviv against the massacre. And equally chilling to reflect that some of those one million – if the polls are accurate – may well be voting for Mr Sharon today.

“Ariel Sharon was responsible,” a well-dressed young man shouted at us from an apartment balcony yesterday morning. And who could disagree? Israel had invaded Lebanon on 6 June 1982 with a plan – known to Sharon but not vouchsafed to his Likud prime minister, Menachem Begin – to advance all the way to Beirut and surround Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organisation guerrillas in the Lebanese capital. Officially named “Operation Peace for Galilee” (the real Israeli military codename was “Snowball”), the invasion was supposedly a response to PLO rocket attacks across the Israeli border.

But the rocket attacks had followed a series of Israeli air-raids on Lebanon which had ended a UN-brokered ceasefire and which were supposedly in “retaliation” for the attempted murder of the Israeli ambassador to London – though his would-be killers came from the Abu Nidal group which had nothing to do with the PLO and hated Arafat. But Sharon had anyway received an earlier American “green light” for his operation from Alexander Haig in the spring of 1982. After two months and almost 17,000 deaths, most of them civilians – the majority killed by Israeli gunfire and air attack – the PLO withdrew from Beirut under international protection, leaving their unarmed families behind.

At which point Sharon announced that 2,000 “terrorists” remained in the Sabra and Chatila camps. These mythical “terrorists” prompted a small advance by Israeli tanks – contrary to an agreement with Washington – towards the Palestinian camps. A French UN officer who tried to photograph the advance was shot dead by an “unknown” sniper. Sharon repeated his extraordinary claim that “terrorists” remained in the camps. And it was then that the Christian Lebanese president-elect, Bashir Gemayel – the leader of the Phalange militia which had already murdered thousands of surrendering Palestinians in the Tel el-Zaatar camp in 1976 – was assassinated.

Sharon paid his condolences to Gemayel’s father, Pierre. He must have known the old man’s history. Pierre Gemayel had founded his party after being inspired by the Olympics in Nazi Germany in 1936 (“I liked their idea of order,” he once confided to me). Not for nothing did Israel’s militia allies use the fascist “Phalange” as their name. As the Christians prepared to bury their hero, Sharon – again contrary to assurances he had given the Americans – ordered the Israeli army into west Beirut to “restore order”.

The Israelis then asked the Christian Phalange – armed and uniformed by Israel and allied to Israel since 1976 – to enter the Israeli-surrounded camps to “liquidate” the “terrorists”. Which is why, on Thursday 16 September, guided by signposts which the Israelis had laid across a Beirut airport runway, the Christian gunmen walked through the southern entrance of Chatila, some of them drunk, a number on drugs – all under the eyes of the Israelis – and embarked on a war crime.

Today, much scarred by later wars, the lanes of Chatila still follow the same paths I walked down 18 years ago. There are always survivors who have never told their stories to us before. Yesterday I wandered up an alleyway – rippling with water pipes and running with rain and sewage – to find a middle-aged woman buying tomatoes from a stall. I was 30 metres from the road where I discovered Mr Nouri’s body almost two decades ago. She took me to her family home and introduced me to her daughter, Nadia Salameh. Nadia was only 12 when Ariel Sharon’s soldiers watched the Phalangist militia slaughter their way through the camps.

“At the end of this alleyway outside our home, we were all shocked by what we saw,” she told me, her voice slowly rising with the memory of horror. “I saw corpses there, seven deep, some decapitated, others with their throats slit. One of our neighbours was lying there, Um Ahmed Saad, and her body had grown big with the heat. Her hands had been chopped off at the wrists. She used to wear a lot of bracelets, a lot of gold. The Phalange obviously wanted the gold.”

Each house I enter contains the faded photographs of young men killed in the war, some by Israel’s allies, others by Shia Muslim gunmen in the later 1985 camps war. But their memories have not faded. Old Abdullah – he is 78 and pleaded with us not to use his family name – talks without looking at me, eyes staring at the wall. The ghosts are returning again. “The Phalange were led by Elie Hobeika,” he said, “but who sent them into the camps? The Israelis. And who was the defence minister? Sharon. They put their tanks round the camp. I was part of a delegation that tried to negotiate with them. We carried a white flag. When we got near, there was a man’s voice on a loudspeaker telling us to have our identity cards ready. But I didn’t have my ID. So I went back home. And it turned out the loudspeaker was being used by a Phalangist. And they murdered all the men in the delegation. I was the only one to survive.”

There was no doubt that the Israelis could see what the Lebanese Christian Phalange were doing. The Kahan commission was later to quote Lieutenant Avi Grabovski, deputy commander of an Israeli tank unit that was helping to encircle the camp: he watched the murder of five women and children and wanted to protest, but his battalion commander had replied to another soldier who complained that “we know, it’s not to our liking, and don’t interfere”. Up to 2,000 Palestinians were murdered – two mass graves remain unexhumed in Beirut – and Sharon’s reputation, already besmirched by the much earlier slaughter of more than 50 Palestinian civilians by his Commando Unit 101, seemed as buried as the Palestinian victims.

But like the garbage that has collected over the only known mass grave, the historical narrative – save for that of the survivors – has become overgrown. History moves on. Arafat recognised Israel and found himself trapped by an agreement that would give him neither a real “Palestine” nor secure the return of the refugees – including those in Sabra and Chatila – to what is now Israel. And the new leader of Israel is, within hours, likely to be the man who allowed the killers into the Beirut camps more than 18 years ago.

With power, of course, comes respect. CNN now calls Sharon “a barrel-framed veteran general who has built a reputation for flattening obstacles and reshaping Israel’s landscape”, while the BBC World Service on Sunday managed to avoid the fateful words Sabra and Chatila by referring only to his “chequered military career”. As for Nadia Salameh, “Sharon’s role here shows what he is capable of. If Sharon is elected, the whole peace process falls by the wayside because he doesn’t want peace.” It’s a relief to recall that up to a million Israelis demonstrated their moral integrity in 1982 by protesting in Tel Aviv against the massacre. And equally chilling to reflect that some of those one million – if the polls are accurate – may well be voting for Mr Sharon today.