17 sept 2002

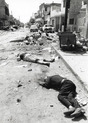

The dead lie in the streets of Sabra and Shatila

On a hot and muggy Saturday morning twenty years ago, a shocking reality came to light in Lebanon. People approaching the contiguous refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila on the outskirts of Beirut that day suspected that dark deeds had taken place in the alleyways, homes, and streets of the camps for a day or more. Three days earlier, Israeli troops and tanks had surrounded the camps as the area came under constant artillery fire.

Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers, commanded by General Ariel Sharon and assisted by Generals Rafael Eitan and Amos Yaron, had prevented anyone from entering or leaving the camp — anyone, that was, but Israeli-backed, -armed, and -supplied Phalangist militiamen, infamous for their murderous hatred of Palestinians. At night, IDF soldiers had launched illumination flares into the sky to assist these militiamen in their gruesome tasks, the results of which would appall the world by the evening of that September Saturday two decades ago.

Yet even before the journalists, diplomats, Red Cross personnel and others had entered the camps that morning, their worst fears were confirmed by the nauseating smell of putrefying flesh and the audible drone of feasting flies, the only sound to break the stifling silence before the anguished screams of survivors shattered the air. Hardened journalists vomited. Grown men fainted. Seasoned Red Cross representatives were dazed.

“I divide my life into before and after Sabra and Shatila,” said Elias, a former Red Cross volunteer with whom I worked in Lebanon. “I was not the same person after I saw the severed bodies of babies and the corpses of women with their stomachs ripped open. For weeks, I imagined I could still smell all those bodies stinking in the heat of that morning. It completely altered my view of human nature.”

Only seventeen at the time, Elias was among the youngest of those to discover one of the worst atrocities of the post-World War II era in the refugee camps on September 18, 1982. Now approaching his forties, he will never forget that date or its significance.

Unfortunately, many people do not know, let alone remember, that the Sabra and Shatila massacres occurred.

Some, upon learning that at least 1,500 innocent Lebanese and Palestinian civilians were tortured, raped, mutilated and then slaughtered in a two-day orgy of murder and mayhem, after a summer in which the invading Israeli army committed numerous war crimes resulting in the deaths of over 15,000 civilians, simply shrug, as if to say “Oh, well, what can one do? That’s the Middle East, after all. Things like that happen over there all the time.”

But massacres don’t “just happen.” They are not natural disasters, like earthquakes, tornadoes, or tidal waves. Massacres require thought, planning, and coordination. Massacres arise from calculated strategies and the cunning manipulation of emotions, facts, and rationales. They require a particular set of interlocking social roles and a specific pattern of behaviors. Every massacre has its own political organization, propped up by a set of motivating beliefs and legitimating ideologies.

Massacres don’t erupt spontaneously, like barroom brawls. When an army is involved—as was clearly the case 20 years ago in Beirut, a divided city under Israeli military occupation—massacres also require a chain of command. Orders are given, tanks are deployed, papers are checked and approved, passage is denied, roads are blocked, exits are sealed, flares are launched, soldiers are transported across demarcation lines, murderers are provisioned, mass graves are dug, corpses are concealed, people are disappeared, and then stories are spun, excuses are offered, and—always— facts are denied. The first casualty of every war and the last casualty of every massacre is the same: the truth.

Under international law, specifically the IV Geneva Conventions, command responsibility for war crimes ultimately rests upon the shoulders of the highest-ranking military officers present. In the case of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, that person was and remains General Ariel Sharon. The fact that, 20 years later, Sharon is a sitting head of state enjoying the perquisites of power and prestige while the dead of Sabra and Shatila lie forgotten in unmarked graves should be cause for widespread alarm and outrage. The absence of such is sinister; it comprises evidence of other, ongoing and metaphorical, murders.

The Dangers of Impunity

Massacres have authors; they are crimes that must be investigated and prosecuted. For the bereaved, massacres never end until justice is done. Every day since that horrific Saturday in 1982 has been September 18th over and over again for the survivors of Sabra and Shatila. To forget a massacre is to kill the dead a second time; to forget the dead is to condone the crime and to excuse the killers. And the dead of Sabra and Shatila have been killed many, many times. Every time another anniversary passed and no one marked it, every time garbage desecrated the mass grave site, every time the Lebanese authorities refused to investigate or prosecute the crimes, not only the dead, but also the tormented survivors, were murdered again and again.

Today’s 20th anniversary of the massacres goes unmentioned in major newspapers. The significance of this date will not be commented upon by news anchors. The killers are now “honorable men” and masters of the dark arts of PR spin. They are well-protected by friends in high places in government and media.

Every time Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who, according to an official Israeli commission of inquiry “bears personal responsibility” for the massacres, is warmly welcomed in Western capitals and heralded as a “man of peace,” the truth is murdered once more. This is how impunity flourishes, how laws are rendered meaningless, and how the delicate fabric of human social and political affairs gradually erodes.

Continued impunity for the Sabra and Shatila massacres is not only morally reprehensible and psychologically unbearable, but also politically dangerous because of the precedent it sets and the hearts and minds it poisons. He who is denied justice will seek revenge. The evil of a crime condoned festers and spreads, eventually touching others, even miles away and decades later.

An Agonizing Anniversary

On a hot and muggy Saturday morning twenty years ago, a shocking reality came to light in Lebanon. People approaching the contiguous refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila on the outskirts of Beirut that day suspected that dark deeds had taken place in the alleyways, homes, and streets of the camps for a day or more. Three days earlier, Israeli troops and tanks had surrounded the camps as the area came under constant artillery fire.

Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers, commanded by General Ariel Sharon and assisted by Generals Rafael Eitan and Amos Yaron, had prevented anyone from entering or leaving the camp — anyone, that was, but Israeli-backed, -armed, and -supplied Phalangist militiamen, infamous for their murderous hatred of Palestinians. At night, IDF soldiers had launched illumination flares into the sky to assist these militiamen in their gruesome tasks, the results of which would appall the world by the evening of that September Saturday two decades ago.

Yet even before the journalists, diplomats, Red Cross personnel and others had entered the camps that morning, their worst fears were confirmed by the nauseating smell of putrefying flesh and the audible drone of feasting flies, the only sound to break the stifling silence before the anguished screams of survivors shattered the air. Hardened journalists vomited. Grown men fainted. Seasoned Red Cross representatives were dazed.

“I divide my life into before and after Sabra and Shatila,” said Elias, a former Red Cross volunteer with whom I worked in Lebanon. “I was not the same person after I saw the severed bodies of babies and the corpses of women with their stomachs ripped open. For weeks, I imagined I could still smell all those bodies stinking in the heat of that morning. It completely altered my view of human nature.”

Only seventeen at the time, Elias was among the youngest of those to discover one of the worst atrocities of the post-World War II era in the refugee camps on September 18, 1982. Now approaching his forties, he will never forget that date or its significance.

Unfortunately, many people do not know, let alone remember, that the Sabra and Shatila massacres occurred.

Some, upon learning that at least 1,500 innocent Lebanese and Palestinian civilians were tortured, raped, mutilated and then slaughtered in a two-day orgy of murder and mayhem, after a summer in which the invading Israeli army committed numerous war crimes resulting in the deaths of over 15,000 civilians, simply shrug, as if to say “Oh, well, what can one do? That’s the Middle East, after all. Things like that happen over there all the time.”

But massacres don’t “just happen.” They are not natural disasters, like earthquakes, tornadoes, or tidal waves. Massacres require thought, planning, and coordination. Massacres arise from calculated strategies and the cunning manipulation of emotions, facts, and rationales. They require a particular set of interlocking social roles and a specific pattern of behaviors. Every massacre has its own political organization, propped up by a set of motivating beliefs and legitimating ideologies.

Massacres don’t erupt spontaneously, like barroom brawls. When an army is involved—as was clearly the case 20 years ago in Beirut, a divided city under Israeli military occupation—massacres also require a chain of command. Orders are given, tanks are deployed, papers are checked and approved, passage is denied, roads are blocked, exits are sealed, flares are launched, soldiers are transported across demarcation lines, murderers are provisioned, mass graves are dug, corpses are concealed, people are disappeared, and then stories are spun, excuses are offered, and—always— facts are denied. The first casualty of every war and the last casualty of every massacre is the same: the truth.

Under international law, specifically the IV Geneva Conventions, command responsibility for war crimes ultimately rests upon the shoulders of the highest-ranking military officers present. In the case of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, that person was and remains General Ariel Sharon. The fact that, 20 years later, Sharon is a sitting head of state enjoying the perquisites of power and prestige while the dead of Sabra and Shatila lie forgotten in unmarked graves should be cause for widespread alarm and outrage. The absence of such is sinister; it comprises evidence of other, ongoing and metaphorical, murders.

The Dangers of Impunity

Massacres have authors; they are crimes that must be investigated and prosecuted. For the bereaved, massacres never end until justice is done. Every day since that horrific Saturday in 1982 has been September 18th over and over again for the survivors of Sabra and Shatila. To forget a massacre is to kill the dead a second time; to forget the dead is to condone the crime and to excuse the killers. And the dead of Sabra and Shatila have been killed many, many times. Every time another anniversary passed and no one marked it, every time garbage desecrated the mass grave site, every time the Lebanese authorities refused to investigate or prosecute the crimes, not only the dead, but also the tormented survivors, were murdered again and again.

Today’s 20th anniversary of the massacres goes unmentioned in major newspapers. The significance of this date will not be commented upon by news anchors. The killers are now “honorable men” and masters of the dark arts of PR spin. They are well-protected by friends in high places in government and media.

Every time Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who, according to an official Israeli commission of inquiry “bears personal responsibility” for the massacres, is warmly welcomed in Western capitals and heralded as a “man of peace,” the truth is murdered once more. This is how impunity flourishes, how laws are rendered meaningless, and how the delicate fabric of human social and political affairs gradually erodes.

Continued impunity for the Sabra and Shatila massacres is not only morally reprehensible and psychologically unbearable, but also politically dangerous because of the precedent it sets and the hearts and minds it poisons. He who is denied justice will seek revenge. The evil of a crime condoned festers and spreads, eventually touching others, even miles away and decades later.

An Agonizing Anniversary

A woman cries at the loss of relatives

Today, the 20th anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, may well be the most painful to date for the bereaved. Last year, 23 courageous survivors lodged a case against Ariel Sharon, Amos Yaron, and other Israelis and Lebanese in a Belgian court under the principle of Universal Jurisdiction in the hopes of finally attaining justice for the dead and closure for the living. The principle of universal jurisdiction, encoded in the IV Geneva Conventions, international humanitarian law and the 1984 Convention on Torture, is based on customary law as well as a consensus, strengthened by the horrors of World War II, that some crimes are so heinous that they threaten the entire human race.

The jurisdiction for prosecuting these crimes must be universal, not simply territorial. The Geneva Conventions specifically state that all signatories to the convention have not only the right but indeed the duty to either prosecute or extradite individuals guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. In 1993, the Belgian Parliament formally incorporated the principle of Universal Jurisdiction into Belgium’s criminal code, thereby enabling Belgian courts to hear war crimes cases having no connection to Belgium.

Despite careful documentation and extensive testimonies, despite the consistent support of the Brussels Attorney-General for the arguments presented by the massacre survivors, not those of the lawyers representing the accused, during the pre-trial hearing; and despite new evidence further implicating IDF personnel in the massacres as well as in the disappearance of hundreds of men and boys in the immediate aftermath of the killings, a Belgian Appeals Court threw the case out last June on an absurd technicality: The case could not proceed to trial because the accused were “not present on Belgian soil.”

International legal specialists, no less than Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, noted that this ruling made a mockery of the principle of universal jurisdiction for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Yet another murder has now emanated from the Sabra and Shatila massacres: the murder of popular faith in the principles, processes, and efficacy of international law.

With this decision by a Belgian Appeals Court, the consequences of the crimes committed twenty years ago in Beirut took on new and disturbing international dimensions. The massacres at Sabra and Shatila are no longer simply the bloodiest chapter in the Arab-Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but rather, a glaring reminder and a disturbing proof of the international community’s failure to apply international law fairly and consistently.

Another Attempt at Justice?

Next month, the Belgian Parliament, at the urging of a broad-based coalition of NGOs and individuals representing a diversity of political viewpoints, is expected to pass a new item of interpretive legislation that will salvage the country’s Universal Jurisdiction law and will clarify that accused parties need not be present on Belgian soil for a case to proceed to trial. Should this proposed legislation pass, it will render the Sabra and Shatila massacre survivors’ appeal to the Belgian Supreme Court unnecessary, enabling them to launch another attempt at justice in Belgium for the 1982 massacres in Beirut.

After twenty years of unimaginable anguish, the survivors of Sabra and Shatila are still hoping to attain justice, to lay their dead to rest in peace, and to begin to live again. But justice, like a massacre, does not just happen. Considerable coordination, effort, patience, and skill will be required before the survivors can finally turn the page on the black date of September 18th.

Today, the 20th anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, may well be the most painful to date for the bereaved. Last year, 23 courageous survivors lodged a case against Ariel Sharon, Amos Yaron, and other Israelis and Lebanese in a Belgian court under the principle of Universal Jurisdiction in the hopes of finally attaining justice for the dead and closure for the living. The principle of universal jurisdiction, encoded in the IV Geneva Conventions, international humanitarian law and the 1984 Convention on Torture, is based on customary law as well as a consensus, strengthened by the horrors of World War II, that some crimes are so heinous that they threaten the entire human race.

The jurisdiction for prosecuting these crimes must be universal, not simply territorial. The Geneva Conventions specifically state that all signatories to the convention have not only the right but indeed the duty to either prosecute or extradite individuals guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. In 1993, the Belgian Parliament formally incorporated the principle of Universal Jurisdiction into Belgium’s criminal code, thereby enabling Belgian courts to hear war crimes cases having no connection to Belgium.

Despite careful documentation and extensive testimonies, despite the consistent support of the Brussels Attorney-General for the arguments presented by the massacre survivors, not those of the lawyers representing the accused, during the pre-trial hearing; and despite new evidence further implicating IDF personnel in the massacres as well as in the disappearance of hundreds of men and boys in the immediate aftermath of the killings, a Belgian Appeals Court threw the case out last June on an absurd technicality: The case could not proceed to trial because the accused were “not present on Belgian soil.”

International legal specialists, no less than Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, noted that this ruling made a mockery of the principle of universal jurisdiction for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Yet another murder has now emanated from the Sabra and Shatila massacres: the murder of popular faith in the principles, processes, and efficacy of international law.

With this decision by a Belgian Appeals Court, the consequences of the crimes committed twenty years ago in Beirut took on new and disturbing international dimensions. The massacres at Sabra and Shatila are no longer simply the bloodiest chapter in the Arab-Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but rather, a glaring reminder and a disturbing proof of the international community’s failure to apply international law fairly and consistently.

Another Attempt at Justice?

Next month, the Belgian Parliament, at the urging of a broad-based coalition of NGOs and individuals representing a diversity of political viewpoints, is expected to pass a new item of interpretive legislation that will salvage the country’s Universal Jurisdiction law and will clarify that accused parties need not be present on Belgian soil for a case to proceed to trial. Should this proposed legislation pass, it will render the Sabra and Shatila massacre survivors’ appeal to the Belgian Supreme Court unnecessary, enabling them to launch another attempt at justice in Belgium for the 1982 massacres in Beirut.

After twenty years of unimaginable anguish, the survivors of Sabra and Shatila are still hoping to attain justice, to lay their dead to rest in peace, and to begin to live again. But justice, like a massacre, does not just happen. Considerable coordination, effort, patience, and skill will be required before the survivors can finally turn the page on the black date of September 18th.

12 mar 2002

Imagine that it is September 2010. The site of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan is just a garbage dump now.

Weather permitting, teenagers meet to play pick-up games of soccer or baseball in this space filled with the ashes of thousands. The photos of the innocents who perished unjustly in the shocking attacks nine years earlier have faded into oblivion. All of the makeshift altars and memorials to the dead are long gone, and no one remembers their names. Not a single monument to their senseless erasure from the world of the living has ever been erected.

Worse still, no one has been punished for these heinous crimes. Not one person has ever stood trial for the murders of thousands of innocent office workers and airplane passengers that bright September day nearly a decade ago. The whole event has, in fact, been pushed off the public stage and relegated to the private memories of the bereaved. They have gradually come to realize that their grief must remain unspoken. No one responds when they raise questions of justice, accountability, or the sacred duty to honor the dead. People get annoyed whenever they bring up the troubling events of September 11, 2001, so they have learned, after nine years, to suffer in silence and pretend that it was no big deal, after all.

Such a scenario is not only impossible to imagine, but offensive as well. Six months have passed since planes full of terrified civilians plowed into the twin towers, the Pentagon, and a field in western Pennsylvania. The US has launched a “global war on terror” with no end in sight, countless memorial services have been held, various monuments to the dead are on the drawing table, and the lives mercilessly and unjustly extinguished last September are being commemorated in songs by Neil Young, in special television features, as well as in the pages of the New York Times. No American would stand for the heartless, unjust, and inhumane scenario depicted above. Nor should they—or anyone.

That scenario, however absurd and obscene, is not a hypothetical one, but rather, the daily reality for survivors of one of the most shocking war crimes committed during the last half of the 20th century: the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres in Beirut. Over 1000 unarmed individuals—women, men, children, and the aged—were brutally tortured, raped and slaughtered in September 1982 by Lebanese militiamen allied with and supplied by the Israeli Defense Forces, which, at the time of the massacre, were in complete control of Beirut and under the command of Defense Minister Ariel Sharon. As Israel’s top general at the time of the massacres, Sharon had command responsibility, according to the Geneva Conventions and international law, for anything that happened in Beirut. Israeli units controlled access to and from the camps while the massacre unfolded. The IDF allowed the Lebanese militia to enter the camps and then launched flares into the night skies to assist the killers in their gruesome tasks. The burden of the massacres rests ultimately on Sharon’s shoulders, and indeed, a 1983 Israeli commission of inquiry (which was not legally binding and lacked judicial force) found that Sharon bore “personal responsibility” for the deaths of hundreds of innocent civilians.

The survivors of Sabra and Shatila watched in mute horror, powerless to stop marauding militiamen from exterminating, mutilating, and raping their children, parents, husbands, wives, and friends. The lucky ones know where their loved ones’ bodies are buried; many more, however, still have no clue about the final resting place of their dead. And in the hours and days after the massacres, many Palestinian men and boys were rounded up and trucked away, never to be seen again, most notably from a sports stadium near the refugee camps where Israeli military and intelligence officers were present. A mass grave site at the edge of the refugee camp now does double duty as a garbage dump and an occasional soccer field. Nearly 20 years after the massacre, not a single permanent memorial has been erected to commemorate the dead, not a single person—Israeli or Lebanese—has stood trial for the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the camps of Sabra and Shatila in September 1982. Such impunity is not only morally reprehensible and psychologically unbearable, but also politically dangerous because of the precedent it sets and the hearts and minds it poisons.

For those who covered the Sabra and Shatila massacre as journalists, no less than for those who served as medical workers in the camps’ hospitals that scorching September twenty years ago, this week’s televised images of Israeli tanks surrounding refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza and the photographs of young men lined up, blindfolded and separated from their families as Israeli soldiers point guns at them, are chillingly familiar. Those who have witnessed massacres fear another may unfold at any minute. Those who survived the massacres are incredulous that it might happen again, but this time with the entire world witnessing the killings on prime time television. Those who have followed Ariel Sharon’s biography closely—from the cold-blooded attack on the village of Qibya in 1953 that he orchestrated as leader of the notorious Unit 101, resulting in the deaths of nearly 70 innocent civilians, to his latest threats to wreak large scale destruction and collective punishment on Palestinians who have been trapped in their towns and villages under a long siege—urgently warn that Sharon must be stopped before mass graves are dug again in other refugee camps.

The disturbing events of the last week in the West Bank and Gaza Strip underline the pressing need to dismantle the settlements, end the occupation, and most importantly, to consolidate the rule of law by ensuring international oversight of the occupied territories. What the alarming increase in killings and the disturbing trends in IDF strategy also indicate is an urgent need to end Ariel Sharon’s impunity for war crimes once and for all. And if the recent legal efforts of 23 survivors of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre bear fruit, that may happen sooner than many imagine.

A judicial forum for raising these issues and attaining justice did not exist in September 1982. It does now. On May 15, 2002 arguments will continue before a Belgian court concerning a complaint lodged by massacre survivors accusing Sharon and other Israelis and Lebanese with war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and international law. In the 1990s, Belgium incorporated into its criminal law system the principle of Universal Jurisdiction for war crimes, which is embodied in the Geneva Conventions and international customary law. This has enabled the bereaved sons, daughters, parents, sisters, brothers, and widows of those killed in September 1982 to seek justice, not revenge; to aim for closure, not retaliation; and to honor their dead by taking their case before a court of law and thereby affirming an international order based on universal principles of justice, not a world blinded by the ancient and fruitless principle of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.”

Bringing Ariel Sharon and others to trial for the heinous crimes committed in Sabra and Shatila twenty Septembers ago is just and proper compensation for the victims, and a long overdue remedy for the survivors. They have inhabited a limbo of grief, fear, and bitterness for two decades, suffering not only the horrifying deaths of their loved ones, but the denial of any psychological, moral, or legal closure. But bringing Sharon to trial is equally imperative for those now living under the threat of new massacres in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as the IDF, again under Sharon’s command, displays utter disregard for international law.

The innocents who perished in the camps of Sabra and Shatila in September 1982 are no less human, no less worthy, than the innocents incinerated in New York City, Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania in September 2001. After 20 years of waiting, it is time to lay the dead of Sabra and Shatila to rest, it is time to honor the murdered by holding the murderers accountable. No one would expect Americans to forget the dead of 9/11 and “just get over it and move on,” nor should Americans accept that those directly responsible for the crimes of September 2001 might escape justice before a court of law. If the universal principles undergirding international law are to have any meaning and substance for the coming generations, we should not allow those who committed the crimes of September 1982 to enjoy impunity either.

Please support the global campaign against impunity for war crimes. If you are in the USA, demand that your congressperson and senators take a stand on this issue; write letters to the editor and ask why newspapers and the electronic media in the US have not addressed Ariel Sharon’s long history of war crimes; raise these important issues of justice, morality, and human rights with your colleagues, friends, and neighbors. Join with all those throughout the world who are demanding that the trial in Belgium go forward until justice is done. Ariel Sharon and others must be held accountable for the grave crimes against humanity committed in Sabra and Shatila in 1982.

Dr. Laurie King-Irani is an anthropologist, freelance writer, former editor of MERIP’s Middle East Report, and one of the founders of The Electronic Intifada. She is currently North American Coordinator for the International Campaign for Justice for the Victims of Sabra and Shatila. Laurie and her Lebanese husband, George, live in Victoria, Canada.

Weather permitting, teenagers meet to play pick-up games of soccer or baseball in this space filled with the ashes of thousands. The photos of the innocents who perished unjustly in the shocking attacks nine years earlier have faded into oblivion. All of the makeshift altars and memorials to the dead are long gone, and no one remembers their names. Not a single monument to their senseless erasure from the world of the living has ever been erected.

Worse still, no one has been punished for these heinous crimes. Not one person has ever stood trial for the murders of thousands of innocent office workers and airplane passengers that bright September day nearly a decade ago. The whole event has, in fact, been pushed off the public stage and relegated to the private memories of the bereaved. They have gradually come to realize that their grief must remain unspoken. No one responds when they raise questions of justice, accountability, or the sacred duty to honor the dead. People get annoyed whenever they bring up the troubling events of September 11, 2001, so they have learned, after nine years, to suffer in silence and pretend that it was no big deal, after all.

Such a scenario is not only impossible to imagine, but offensive as well. Six months have passed since planes full of terrified civilians plowed into the twin towers, the Pentagon, and a field in western Pennsylvania. The US has launched a “global war on terror” with no end in sight, countless memorial services have been held, various monuments to the dead are on the drawing table, and the lives mercilessly and unjustly extinguished last September are being commemorated in songs by Neil Young, in special television features, as well as in the pages of the New York Times. No American would stand for the heartless, unjust, and inhumane scenario depicted above. Nor should they—or anyone.

That scenario, however absurd and obscene, is not a hypothetical one, but rather, the daily reality for survivors of one of the most shocking war crimes committed during the last half of the 20th century: the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres in Beirut. Over 1000 unarmed individuals—women, men, children, and the aged—were brutally tortured, raped and slaughtered in September 1982 by Lebanese militiamen allied with and supplied by the Israeli Defense Forces, which, at the time of the massacre, were in complete control of Beirut and under the command of Defense Minister Ariel Sharon. As Israel’s top general at the time of the massacres, Sharon had command responsibility, according to the Geneva Conventions and international law, for anything that happened in Beirut. Israeli units controlled access to and from the camps while the massacre unfolded. The IDF allowed the Lebanese militia to enter the camps and then launched flares into the night skies to assist the killers in their gruesome tasks. The burden of the massacres rests ultimately on Sharon’s shoulders, and indeed, a 1983 Israeli commission of inquiry (which was not legally binding and lacked judicial force) found that Sharon bore “personal responsibility” for the deaths of hundreds of innocent civilians.

The survivors of Sabra and Shatila watched in mute horror, powerless to stop marauding militiamen from exterminating, mutilating, and raping their children, parents, husbands, wives, and friends. The lucky ones know where their loved ones’ bodies are buried; many more, however, still have no clue about the final resting place of their dead. And in the hours and days after the massacres, many Palestinian men and boys were rounded up and trucked away, never to be seen again, most notably from a sports stadium near the refugee camps where Israeli military and intelligence officers were present. A mass grave site at the edge of the refugee camp now does double duty as a garbage dump and an occasional soccer field. Nearly 20 years after the massacre, not a single permanent memorial has been erected to commemorate the dead, not a single person—Israeli or Lebanese—has stood trial for the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the camps of Sabra and Shatila in September 1982. Such impunity is not only morally reprehensible and psychologically unbearable, but also politically dangerous because of the precedent it sets and the hearts and minds it poisons.

For those who covered the Sabra and Shatila massacre as journalists, no less than for those who served as medical workers in the camps’ hospitals that scorching September twenty years ago, this week’s televised images of Israeli tanks surrounding refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza and the photographs of young men lined up, blindfolded and separated from their families as Israeli soldiers point guns at them, are chillingly familiar. Those who have witnessed massacres fear another may unfold at any minute. Those who survived the massacres are incredulous that it might happen again, but this time with the entire world witnessing the killings on prime time television. Those who have followed Ariel Sharon’s biography closely—from the cold-blooded attack on the village of Qibya in 1953 that he orchestrated as leader of the notorious Unit 101, resulting in the deaths of nearly 70 innocent civilians, to his latest threats to wreak large scale destruction and collective punishment on Palestinians who have been trapped in their towns and villages under a long siege—urgently warn that Sharon must be stopped before mass graves are dug again in other refugee camps.

The disturbing events of the last week in the West Bank and Gaza Strip underline the pressing need to dismantle the settlements, end the occupation, and most importantly, to consolidate the rule of law by ensuring international oversight of the occupied territories. What the alarming increase in killings and the disturbing trends in IDF strategy also indicate is an urgent need to end Ariel Sharon’s impunity for war crimes once and for all. And if the recent legal efforts of 23 survivors of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre bear fruit, that may happen sooner than many imagine.

A judicial forum for raising these issues and attaining justice did not exist in September 1982. It does now. On May 15, 2002 arguments will continue before a Belgian court concerning a complaint lodged by massacre survivors accusing Sharon and other Israelis and Lebanese with war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and international law. In the 1990s, Belgium incorporated into its criminal law system the principle of Universal Jurisdiction for war crimes, which is embodied in the Geneva Conventions and international customary law. This has enabled the bereaved sons, daughters, parents, sisters, brothers, and widows of those killed in September 1982 to seek justice, not revenge; to aim for closure, not retaliation; and to honor their dead by taking their case before a court of law and thereby affirming an international order based on universal principles of justice, not a world blinded by the ancient and fruitless principle of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.”

Bringing Ariel Sharon and others to trial for the heinous crimes committed in Sabra and Shatila twenty Septembers ago is just and proper compensation for the victims, and a long overdue remedy for the survivors. They have inhabited a limbo of grief, fear, and bitterness for two decades, suffering not only the horrifying deaths of their loved ones, but the denial of any psychological, moral, or legal closure. But bringing Sharon to trial is equally imperative for those now living under the threat of new massacres in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as the IDF, again under Sharon’s command, displays utter disregard for international law.

The innocents who perished in the camps of Sabra and Shatila in September 1982 are no less human, no less worthy, than the innocents incinerated in New York City, Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania in September 2001. After 20 years of waiting, it is time to lay the dead of Sabra and Shatila to rest, it is time to honor the murdered by holding the murderers accountable. No one would expect Americans to forget the dead of 9/11 and “just get over it and move on,” nor should Americans accept that those directly responsible for the crimes of September 2001 might escape justice before a court of law. If the universal principles undergirding international law are to have any meaning and substance for the coming generations, we should not allow those who committed the crimes of September 1982 to enjoy impunity either.

Please support the global campaign against impunity for war crimes. If you are in the USA, demand that your congressperson and senators take a stand on this issue; write letters to the editor and ask why newspapers and the electronic media in the US have not addressed Ariel Sharon’s long history of war crimes; raise these important issues of justice, morality, and human rights with your colleagues, friends, and neighbors. Join with all those throughout the world who are demanding that the trial in Belgium go forward until justice is done. Ariel Sharon and others must be held accountable for the grave crimes against humanity committed in Sabra and Shatila in 1982.

Dr. Laurie King-Irani is an anthropologist, freelance writer, former editor of MERIP’s Middle East Report, and one of the founders of The Electronic Intifada. She is currently North American Coordinator for the International Campaign for Justice for the Victims of Sabra and Shatila. Laurie and her Lebanese husband, George, live in Victoria, Canada.

15 feb 2002

A controversial Belgian court case against the Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, appeared to be over before it had begun last night after the international court of justice ruled that past and present government leaders cannot be tried for war crimes by a foreign state. Mr Sharon has been accused of being responsible for the massacre of hundreds of Palestinians in Lebanon in 1982 when he was Israel's minister of defence. Survivors of the atrocities have started legal proceedings against him in Belgium, where foreign nationals can, exceptionally, be tried for war crimes committed abroad.

Mr Sharon ordered the Israeli army into Lebanon, and it is alleged that he allowed Lebanese Christian Phalangists to run amok in the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps, slaughtering hundreds in cold blood.

But in a landmark judgment, the court in the Haguesaid yesterday that former and current government ministers and leaders are protected from prosecution by a foreign state because of their diplomatic immunity and can only be held to account in their own country.

"The judgment is clear," said Jan Devadder, a legal adviser to the Belgian government. "The court has clearly ruled government leaders and heads of state enjoy total immunity from prosecution. The Sharon case, in my opinion, is closed."

The Israeli government said the judgment vindicated its opposition to the Sharon case.

A Belgian judge was due to rule whether the case should go to trial on March 6, but that decision seems to have been overtaken by yesterday's events.

The judgment is expected to end, once and for all, Belgium's controversial reign as a global war crimes prosecutor for past and present government leaders, a role which has embarrassed the government and strained relations with Israel and other countries.

Under a 1993 law, Belgium gave itself the right to try war crimes committed by anyone anywhere at any time and has since been flooded with legal complaints against a string of high-profile leaders.

Cases against the Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat, the Cuban president, Fidel Castro, and the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein, are all pending.

But legal experts predicted last night that these cases will now be dropped and Belgium's self-styled role as an international war crimes prosecutor will be brought to an end because the world court has effectively ruled that diplomatic immunity takes pre cedence over everything else.

The court said a former or serving government official could not be tried in a foreign court because "throughout the duration of his or her office [the minister], when abroad, enjoys full immunity from criminal jurisdiction". That principle held good, the court added, regardless of whether the accused was abroad on official business or in a private capacity.

Human rights activists called the ruling a dark day for global justice and argued that those guilty of war crimes would never be put on trial in their own countries.

"Government ministers who commit crimes against humanity are not likely to be prosecuted at home, and this ruling means they will enjoy impunity abroad as well," said Reed Brody of New York-based Human Rights Watch.

Privately, the Belgian government is likely to be relieved. The foreign minister, Louis Michel, conceded last night that his country's war crimes legislation contained "some inconvenient aspects" that would have to be "corrected".

The judgment does not have any bearing on the trial of the likes of Slobodan Milosevic, as he is being tried by an international body, the United Nations, and not by an individual foreign government.

Mr Sharon ordered the Israeli army into Lebanon, and it is alleged that he allowed Lebanese Christian Phalangists to run amok in the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps, slaughtering hundreds in cold blood.

But in a landmark judgment, the court in the Haguesaid yesterday that former and current government ministers and leaders are protected from prosecution by a foreign state because of their diplomatic immunity and can only be held to account in their own country.

"The judgment is clear," said Jan Devadder, a legal adviser to the Belgian government. "The court has clearly ruled government leaders and heads of state enjoy total immunity from prosecution. The Sharon case, in my opinion, is closed."

The Israeli government said the judgment vindicated its opposition to the Sharon case.

A Belgian judge was due to rule whether the case should go to trial on March 6, but that decision seems to have been overtaken by yesterday's events.

The judgment is expected to end, once and for all, Belgium's controversial reign as a global war crimes prosecutor for past and present government leaders, a role which has embarrassed the government and strained relations with Israel and other countries.

Under a 1993 law, Belgium gave itself the right to try war crimes committed by anyone anywhere at any time and has since been flooded with legal complaints against a string of high-profile leaders.

Cases against the Palestinian leader, Yasser Arafat, the Cuban president, Fidel Castro, and the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein, are all pending.

But legal experts predicted last night that these cases will now be dropped and Belgium's self-styled role as an international war crimes prosecutor will be brought to an end because the world court has effectively ruled that diplomatic immunity takes pre cedence over everything else.

The court said a former or serving government official could not be tried in a foreign court because "throughout the duration of his or her office [the minister], when abroad, enjoys full immunity from criminal jurisdiction". That principle held good, the court added, regardless of whether the accused was abroad on official business or in a private capacity.

Human rights activists called the ruling a dark day for global justice and argued that those guilty of war crimes would never be put on trial in their own countries.

"Government ministers who commit crimes against humanity are not likely to be prosecuted at home, and this ruling means they will enjoy impunity abroad as well," said Reed Brody of New York-based Human Rights Watch.

Privately, the Belgian government is likely to be relieved. The foreign minister, Louis Michel, conceded last night that his country's war crimes legislation contained "some inconvenient aspects" that would have to be "corrected".

The judgment does not have any bearing on the trial of the likes of Slobodan Milosevic, as he is being tried by an international body, the United Nations, and not by an individual foreign government.