23 jan 2012

During the First Intifada, a group of young Palestinian boys throwing stones at Israeli soldiers in the Gaza Strip

This article was written by Patrick Truffer for the University of St Andrews. It was published in the Small Wars Journal 8, No 2 on February 4, 2012. You can download the article in PDF-format with footnotes, annexes and a refrence list.

Introduction

The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) – the basic document of Hamas – was formulated on the 18th August 1988. Nevertheless, Hamas was not founded on a single day – the foundation was a process, which started at the beginning of the First Intifada in December 1987. In 1973, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, spiritual leader and founder of Hamas, established the al-Mujamma’al-Islami (the Islamic Centre) to coordinate the Muslim Brotherhood’s political activities in the Gaza Strip.

When the First Intifada broke out, a young generation of Muslim Brothers was willing to participate, but leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood were reluctant to involve the movement and feared a bad reputation for it, should the Intifada fail. This younger generation gathered around Yassin and the activities of the group were labelled under the name Hamas. Finally, Hamas became a spin-off of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas is based on two ideological pillars: a political and a religious one. The movement follows a pan-Palestinian nationalistic policy and on the religious dimension, Hamas propagates an Islamic fundamentalist ideology.

Unlike the Muslim Brothers, Hamas is more focused on a local level. Its strategic goals are to free Palestine from the “Zionist invaders” (cf.: Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement“, Lillian Goldman Law Library, 18.08.1988, article 7) to obliterate Israel and to establish an Islamic state in Palestine. Hamas defines the struggle for Palestine as a religious obligation and interconnects the political and religious pillars with each other. The anti-Zionistic approach of the Covenant is not only mixed with an anti-Semitic attitude, but supports the idea of killing Jews (cf.: ibid).

The belief in a Jewish world conspiracy based on the fictional “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” is a part of the anti-Semitic rhetorics. Hamas refuses any peace negotiations because “the land of Palestine is an [impartible] Islamic Waqf [(religious endowment)] [sic] consecrated for future Moslem generations until Judgement Day” (cf.: ibid, article 11). Therefore, Hamas rejects the Camp David Accords as well. Despite its political activities from the beginning of its existence, Hamas boycotted the parliamentary elections in 1996 and the presidential one in 2005, but participated in the municipal elections in 2004/2005 and in the parliamentary elections in 2006, listed under the name “Change and Reform”. In 2006, the movement won 74 of total 132 seats in the Palestinian Legislative Council.

This article was written by Patrick Truffer for the University of St Andrews. It was published in the Small Wars Journal 8, No 2 on February 4, 2012. You can download the article in PDF-format with footnotes, annexes and a refrence list.

Introduction

The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) – the basic document of Hamas – was formulated on the 18th August 1988. Nevertheless, Hamas was not founded on a single day – the foundation was a process, which started at the beginning of the First Intifada in December 1987. In 1973, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, spiritual leader and founder of Hamas, established the al-Mujamma’al-Islami (the Islamic Centre) to coordinate the Muslim Brotherhood’s political activities in the Gaza Strip.

When the First Intifada broke out, a young generation of Muslim Brothers was willing to participate, but leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood were reluctant to involve the movement and feared a bad reputation for it, should the Intifada fail. This younger generation gathered around Yassin and the activities of the group were labelled under the name Hamas. Finally, Hamas became a spin-off of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas is based on two ideological pillars: a political and a religious one. The movement follows a pan-Palestinian nationalistic policy and on the religious dimension, Hamas propagates an Islamic fundamentalist ideology.

Unlike the Muslim Brothers, Hamas is more focused on a local level. Its strategic goals are to free Palestine from the “Zionist invaders” (cf.: Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement“, Lillian Goldman Law Library, 18.08.1988, article 7) to obliterate Israel and to establish an Islamic state in Palestine. Hamas defines the struggle for Palestine as a religious obligation and interconnects the political and religious pillars with each other. The anti-Zionistic approach of the Covenant is not only mixed with an anti-Semitic attitude, but supports the idea of killing Jews (cf.: ibid).

The belief in a Jewish world conspiracy based on the fictional “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” is a part of the anti-Semitic rhetorics. Hamas refuses any peace negotiations because “the land of Palestine is an [impartible] Islamic Waqf [(religious endowment)] [sic] consecrated for future Moslem generations until Judgement Day” (cf.: ibid, article 11). Therefore, Hamas rejects the Camp David Accords as well. Despite its political activities from the beginning of its existence, Hamas boycotted the parliamentary elections in 1996 and the presidential one in 2005, but participated in the municipal elections in 2004/2005 and in the parliamentary elections in 2006, listed under the name “Change and Reform”. In 2006, the movement won 74 of total 132 seats in the Palestinian Legislative Council.

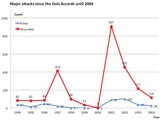

Table 1: Major attacks by Hamas since the Oslo Accords until 2004. Because it covers only the major attacks, Table 1 gives only a qualitative impression of their intensity.

The violent history and a possible moderation of Hamas combined with an increased political participation can be explained with the theory of “Social Mobilisation“. According to this theory, social groups tend to use violence in case of refused political participation.

For example: the limited possibility of the Shiite population to participate in the Lebanon political system was one of the factors, which led to the foundation of Hezbollah (cf.: An Islamic Janus Face – Hezbollah as a power-political factor in the Middle East); in December 1991, after cancellation of elections in Algeria, which promised the Islamic party a success, supporters of the Islamic Salvation Front took up weapons, which led to a 10 years enduring civil war (cf.: Mohammed M. Hafez, “Why Muslims rebel: repression and resistance in the Islamic world“, Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003, p.1); “A quantitative examination of the development of IRA violence in a community mobilized for peaceful protest shows that state repression, not economic deprivation, was the major determinant of this violence” (Source: Robert W. White, “From Peaceful Protest to Guerrilla War: Micromobilization of the Provisional Irish Republican Army“, American Journal of Sociology 94, no. 6, 1989, p.1277).

In case social-economical factors lead to radicalisation of social groups, these groups will not have the chance to change their situation without political involvement. Political participation is a key factor to avoid violence in a long-term – social groups turn to violence, when they do not see another way. With the opportunity to form political parties, compete in elections and participate in legislative, executive and judicial processes, there is a chance that social groups renounce violence in a long-term (cf.: ibid, p.28-31,65,207f).

According to this thesis, Hamas might soften its course after the takeover of political responsibility. The participation of Hamas in the elections can be interpreted as a sign of moderation. The key to explaining [group’s] militancy is not economic stagnation or excessive secularisation, but the lack of meaningful access to state institutions. — Hafez, “Why Muslims rebel: repression and resistance in the Islamic world“, p.18.

The aim of this article is to analyse whether Hamas attitude has become more moderate after 2006, when it increased its involvement in the political process of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). The declining importance of the Covenant for Hamas policy and the decreasing number of attacks against Israel could be an indicator of moderation.

Obstructing the peace process

The violent history and a possible moderation of Hamas combined with an increased political participation can be explained with the theory of “Social Mobilisation“. According to this theory, social groups tend to use violence in case of refused political participation.

For example: the limited possibility of the Shiite population to participate in the Lebanon political system was one of the factors, which led to the foundation of Hezbollah (cf.: An Islamic Janus Face – Hezbollah as a power-political factor in the Middle East); in December 1991, after cancellation of elections in Algeria, which promised the Islamic party a success, supporters of the Islamic Salvation Front took up weapons, which led to a 10 years enduring civil war (cf.: Mohammed M. Hafez, “Why Muslims rebel: repression and resistance in the Islamic world“, Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003, p.1); “A quantitative examination of the development of IRA violence in a community mobilized for peaceful protest shows that state repression, not economic deprivation, was the major determinant of this violence” (Source: Robert W. White, “From Peaceful Protest to Guerrilla War: Micromobilization of the Provisional Irish Republican Army“, American Journal of Sociology 94, no. 6, 1989, p.1277).

In case social-economical factors lead to radicalisation of social groups, these groups will not have the chance to change their situation without political involvement. Political participation is a key factor to avoid violence in a long-term – social groups turn to violence, when they do not see another way. With the opportunity to form political parties, compete in elections and participate in legislative, executive and judicial processes, there is a chance that social groups renounce violence in a long-term (cf.: ibid, p.28-31,65,207f).

According to this thesis, Hamas might soften its course after the takeover of political responsibility. The participation of Hamas in the elections can be interpreted as a sign of moderation. The key to explaining [group’s] militancy is not economic stagnation or excessive secularisation, but the lack of meaningful access to state institutions. — Hafez, “Why Muslims rebel: repression and resistance in the Islamic world“, p.18.

The aim of this article is to analyse whether Hamas attitude has become more moderate after 2006, when it increased its involvement in the political process of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). The declining importance of the Covenant for Hamas policy and the decreasing number of attacks against Israel could be an indicator of moderation.

Obstructing the peace process

With the end of the First Intifada and the signing of the Oslo Accords in September 1993, the situation changed for all parties in Palestine. Hamas rejected the Oslo Accords based on the Covenant, which says that the territory of Palestine is impartible, and tried to obstruct the peace process between the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Israel with a series of assassinations. The movement could not ignore the fact, that the induced peace process was supported by the predominant part of the Palestinians.

Yasser Arafat, later Chairman of the PLO, tried to constrain Hamas with repression and with a better participation in the autonomic structure. In October 1995, leaders of Hamas decided to constitute a political party and participate in the parliamentary elections. Finally, after controversial internal discussions, in December 1995, they refused this idea. Ostensibly, Hamas argued that the parliamentary elections were the consequence of the Oslo Accords, which they reject, but the decision was more based on the fear to face a political defeat. This explains its passive boycott of the elections – in the background, Hamas encouraged Islamists and own members to run as independent candidates and called on its followers to vote for them. Quietly supported by the movement, seven candidates were elected. This limited political engagement did not hinder Hamas to conduct several suicide attacks on Israel territory, highly intensive between 1996 and 1998.

During this period, the movement was not seeking a real political participation. Instead, its leaders were more concerned about losing the grass-root support by unpopular decisions, such as an active boycott with a prohibition to vote for its members, who would likely violate it. The attacks decreased between October 1998 and September 1999, due to the pressure from Israel and the PNA, coordinated by the CIA (cf.: Ely Karmon, “Hamas’ Terrorism Strategy: Operational limitations and political constraints“, Middle East Review of International Affairs 4, no. 1, March 2000, p.67-68). Finally, in September 2000 the Second Intifada started as a consequence of the failed Middle East Peace Summit at Camp David in July 2000 and Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount.

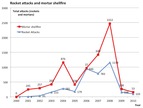

The suicide attacks against Israel peaked again in 2001, but its number declined steadily afterwards. Inspite of that, Hamas started to fire rockets and mortar shells into Israeli territory, which led to Israel’s operation “Cast Lead” in the end of 2008.

The need of legitimacy

Hamas comprises a political, a social and a military wing (the ‘Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam Brigades), which are not really separated from each other. Nevertheless, being a part of a political and social organisation, with its religious, educational and welfare institutions, Hamas is involved in the daily life of ordinary people.

The Hamas leaders are well aware of people’s opinion, which is as important as the religious ideology kept in the Covenant. When they recognised the PNA 1994, which was taken as a product of the Oslo Accords, Hamas leaders followed the public interest. Shortly after the September 11 attacks, in the light of Palestinians outrage against Islamic terror, Hamas suspended its suicide attacks until 1st October 2001 (source: Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power“, Middle East Journal 61, no. 3, Summer 2007, p.444f.). Both examples show that Hamas is bound in its actions on the legitimacy of the Palestinians and with its increased political participation this dependency has become even stronger.

The voice of the masses, in [Hamas] view, is the expression of God’s will. — Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power“, Middle East Journal 61, no. 3, Summer 2007, p.444.

There are three main factors, which drove Hamas to the decision to participate in the municipal elections in 2004/2005 and in the parliamentary elections in 2006:

Yasser Arafat, later Chairman of the PLO, tried to constrain Hamas with repression and with a better participation in the autonomic structure. In October 1995, leaders of Hamas decided to constitute a political party and participate in the parliamentary elections. Finally, after controversial internal discussions, in December 1995, they refused this idea. Ostensibly, Hamas argued that the parliamentary elections were the consequence of the Oslo Accords, which they reject, but the decision was more based on the fear to face a political defeat. This explains its passive boycott of the elections – in the background, Hamas encouraged Islamists and own members to run as independent candidates and called on its followers to vote for them. Quietly supported by the movement, seven candidates were elected. This limited political engagement did not hinder Hamas to conduct several suicide attacks on Israel territory, highly intensive between 1996 and 1998.

During this period, the movement was not seeking a real political participation. Instead, its leaders were more concerned about losing the grass-root support by unpopular decisions, such as an active boycott with a prohibition to vote for its members, who would likely violate it. The attacks decreased between October 1998 and September 1999, due to the pressure from Israel and the PNA, coordinated by the CIA (cf.: Ely Karmon, “Hamas’ Terrorism Strategy: Operational limitations and political constraints“, Middle East Review of International Affairs 4, no. 1, March 2000, p.67-68). Finally, in September 2000 the Second Intifada started as a consequence of the failed Middle East Peace Summit at Camp David in July 2000 and Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount.

The suicide attacks against Israel peaked again in 2001, but its number declined steadily afterwards. Inspite of that, Hamas started to fire rockets and mortar shells into Israeli territory, which led to Israel’s operation “Cast Lead” in the end of 2008.

The need of legitimacy

Hamas comprises a political, a social and a military wing (the ‘Izz Al-Din Al-Qassam Brigades), which are not really separated from each other. Nevertheless, being a part of a political and social organisation, with its religious, educational and welfare institutions, Hamas is involved in the daily life of ordinary people.

The Hamas leaders are well aware of people’s opinion, which is as important as the religious ideology kept in the Covenant. When they recognised the PNA 1994, which was taken as a product of the Oslo Accords, Hamas leaders followed the public interest. Shortly after the September 11 attacks, in the light of Palestinians outrage against Islamic terror, Hamas suspended its suicide attacks until 1st October 2001 (source: Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power“, Middle East Journal 61, no. 3, Summer 2007, p.444f.). Both examples show that Hamas is bound in its actions on the legitimacy of the Palestinians and with its increased political participation this dependency has become even stronger.

The voice of the masses, in [Hamas] view, is the expression of God’s will. — Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power“, Middle East Journal 61, no. 3, Summer 2007, p.444.

There are three main factors, which drove Hamas to the decision to participate in the municipal elections in 2004/2005 and in the parliamentary elections in 2006:

- In the course of the Second Intifada, the popularity shifted from Fatah to Hamas. In people’s opinion, Fatah failed with its approach to the peace process and could not change anything on the ground. On the other hand, Hamas has an extensive social service network on which the Palestinians depend. Further more, the population recognised Fatah’s internal chaos, corruption and the dysfunction of the institutions of the government, which consisted mainly of Fatah members and supporters. Every time when the Israel Defence Forces would dismantle Fatah’s and PNA’s infrastructure, Fatah stayed helpless and humiliated. This gave Hamas a major support and unlike the parliamentary elections in 1996, a certainty for a good outcome.

- Mahmoud Abbas stated that the Intifada had to stop. According to Hamas scenario, after successful elections, Fatah would be pressured by Israel and the USA to suppress any attacks from Palestinian side against Israel. Without a participation in a new government, this could challenge Hamas course of action. For that reason, it was important for Hamas to have influence on the PNA.

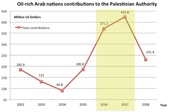

- As long as Hamas has been listed as Special Designated Terrorist in the USA since 1995 and is on the EU’s blacklist of terrorist organisations since 2003, its leaders took into consideration that a broad democratic support from the population could lead to more international legitimacy. Invitations as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people (for example from Turkey and Russia) and additional financial support from some Arab states after the successful elections proved Hamas expectation to be at least partially right.

Table 3: Contribution from Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE to the PNA. Especially Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia increased their contributions when Hamas was in control of the PNA from January 2006 to June 2007 (highlighted in yellow). After the split in the PNA between Hamas and Fatah, the take over the PNA in the Gaza Strip by Hamas, respectively the take over the PNA in the West Bank by Fatah and the forming of the "new PNA" by Fatah in June 2007, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia reduced their contribution to the PNA (Libya and Oman reduced their contributions in the beginning of 2007).

It is evident that Hamas have changed their position toward the PNA and its elections due to the pragmatic approach of the movement. Hamas does not remain in ideological dreams, which retain in the Covenant. Inspite of the fact that the Covenant has not been revoked yet, it is not cited in any of the movement’s political texts and its platform for the elections is quite different (source: Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power“, p.449-53). The Hamas leaders realised that with the legislative participation, new political idiom and terminology was required in their elections manifesto (source: Paul Scham and Osama Abu-Irshaid, “Hamas – Ideological Rigidity and Political Flexibility“, United State Institute of Peace, Special Report 224, 2009, p.12).

It was a logical consequence of a careful and conscious adjustment of their political program for years. After the elections, Hamas officials sounded more moderated in the international press. For example, Khaled Meshaal, head of the political bureau of Hamas, clarified that the conflict with Israel is a political one and not based on a certain belief or culture. Hamas officials stated that they could accept the fact that Israel exists, but they refuse to recognise Israel as a legitimate state.

The most far-reaching offer made by Hamas was the acceptance of a Palestinian state along the 1967 borders with Jerusalem as a capital based on conditions such as: Palestinian refugees get a chance to return, Palestinian agree on a future truce or peace accord with Israel, although Hamas is not obliged to recognise the state of Israel itself. This offer is significant and has to be seen in the context of the Islamic jurisprudence, which Hamas as a fundamental Islamic movement is bound with. Denying these principles would exclude Hamas from the group of those who take Islam seriously as a political guidance (about the view on Hamas through the lens oft he Islamic jurisprudence see Paul Scham and Osama Abu-Irshaid, “Hamas – Ideological Rigidity and Political Flexibility“).

The Covenant is not the Koran, which is unchangeable. I believe that one day it will be changed or replaced according to the views of the Hamas, in order to realize the national interests of the Palestinians. — Muaman Bseiso, a columnist for the Hamas weekly Al-Risala cited in Aaron D. Pina, “Palestinian Elections“, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, 09.02.2006, p.15.

If the Quartet on the Middle East (the United Nations, the United States, the European Union, and Russia) was eager to take the Islamic jurisprudence into consideration, it could probably find a pragmatic way to work with the PNA, which includes ministers from Hamas. Instead of taking an opportunity after the Parliamentary elections to move to a more moderate stance of Hamas in a long-term, the Quartet refuses to speak with representatives from Hamas and the subsidies for the PNA are bound to requirements. The Quartet members demand to recognise Israel’s right to exist, to renounce violence and to accept previous Israeli-Palestinian agreements. These requirements are justified, but it is very unlikely that Hamas will fulfil all three demands at once.

Nevertheless, since early 2006, suicide attacks have largely ceased, and since the operation “Cast Lead” rocket attacks and mortar shellfire have been significantly reduced. After Israel’s operation, Hamas had to choose if it would follow their armed resistance at all costs or effectively govern the Gaza Strip. If Hamas leaders do not want to lose their legitimacy in the population, they have to do their governmental work in a proper way and give the population a perspective – this will not be possible if Hamas attacks provoke a military retaliation by Israel.

At the same time, the need of legitimacy can be a doubled-edged sword. If the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip have the impression that they cannot improve their social-economical life through political participation, then more violence may return. In this case, Hamas most likely would blame Israel for social-economic failures because Israel’s blockade of goods to the Gaza Strip since June 2007 harms the already crippled Palestinian economy further (cf.: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory, “Easing the Blockade“, Special Focus, March 2011).

With new attacks, Hamas could try to keep their legitimacy as an armed resistance movement among the population. If Hamas does not succeed, it is very likely that people in the Gaza Strip turn to other radical groups like the Palestinian Islamic Jihad or the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades. For all involved parties, the choice between moderation and radicalisation is based on a cost-benefit calculation. On 18th March 2011, Hamas fired more than 30 mortars at Israel and on 7th of April an anti-tank weapon, fired from the Gaza Strip, hit an Israel school bus. These could be reactions on the allegations from hardliners that Hamas lost its way as a resistance movement.

There are concerns that if the status quo holds, the massive unemployment and dispiriting living conditions that have persisted and at points worsened since Israel’s withdrawal in 2005 could contribute to further radicalization of the population, decreasing prospects for peace with Israel and for Palestinian unity and increasing the potential for future violence. — Jim Zanotti, “The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations“, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, 30.08.2011, 14.

Conclusion

Hamas has gained more political responsibility due to the participation and winning the parliamentary elections in 2006, but the question whether it has become more moderate cannot be answered cogently. The decision to participate in the legislative elections is a sign of moderation because the involvement in the PNA would possibly require Hamas to deal with Israel and to engage in political compromises. In the past, the movement used to obstructed the peace process actively, now it indirectly accepts at least the Oslo Accords and is willing for new talks, but on their conditions. Hamas officials use a pragmatic approach and before the elections, they separated the ideological principals from political reality.

The evidences of that are speeches of high-ranking Hamas officials and basic documents like the Hamas elections manifesto. Nevertheless, Hamas did not revoke its Covenant. Its ideological fundament given by an aggressively formulated Covenant does not mean, that Hamas is not able to act reasonably in their political work. In fact, PLO had the same problem with its Palestinian National Covenant, which in several paragraphs calls for the destruction of Israel, but the organisation gave the priority to the political reality. Despite the assurance of Yasser Arafat, PLO’s Covenant was never changed or revoked.

It is a challenge to judge if a change of attitude is really a moderation in the case of the largely ceased suicide attacks since early 2006 and the significantly reduced rocket attacks and mortar shellfire since operation “Cast Lead”. If Hamas does not want to lose its legitimacy in the population, it has to avoid actions, which would provoke a military retaliation by Israel, and it has to improve the life conditions of the population with political means. On the other hand, it is not possible to confute the interpretation of these reduced attacks and say that Hamas stopped them after the operation “Cast Lead” only to rehabilitate itself and to upgrade its military capability (cf.: Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, “Terrorism from the Gaza Strip since Operation Cast Lead – Data, Type and Trends“, 17.03.2011).

The biggest argument against a possible moderation of Hamas attitude is the fact, that Hamas is not willing to renounce violent means to reach its goals. This can be explained with the following reasons: after the elections, Israel and the Quartet on the Middle East did not give Hamas a chance to prove its political capacity and to improve the live of the Palestinian population in the Gaza Strip. Israel’s blockade of goods to the Gaza Strip is standing on the way of improvements of Palestinians daily life. If anything, this blockade could give some security for Israel in the short-term, but such measures could be highly counterproductive in the long-term. Social groups especially turn to violence, if they do not see another option to change their situation, and it is important to offer real political alternatives to improve the people life conditions. With their increased political involvement, Hamas leaders did not see any change for the Palestinians, but they will only renounce violence, sure to reach their goals with political means.

Data sources

It is evident that Hamas have changed their position toward the PNA and its elections due to the pragmatic approach of the movement. Hamas does not remain in ideological dreams, which retain in the Covenant. Inspite of the fact that the Covenant has not been revoked yet, it is not cited in any of the movement’s political texts and its platform for the elections is quite different (source: Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power“, p.449-53). The Hamas leaders realised that with the legislative participation, new political idiom and terminology was required in their elections manifesto (source: Paul Scham and Osama Abu-Irshaid, “Hamas – Ideological Rigidity and Political Flexibility“, United State Institute of Peace, Special Report 224, 2009, p.12).

It was a logical consequence of a careful and conscious adjustment of their political program for years. After the elections, Hamas officials sounded more moderated in the international press. For example, Khaled Meshaal, head of the political bureau of Hamas, clarified that the conflict with Israel is a political one and not based on a certain belief or culture. Hamas officials stated that they could accept the fact that Israel exists, but they refuse to recognise Israel as a legitimate state.

The most far-reaching offer made by Hamas was the acceptance of a Palestinian state along the 1967 borders with Jerusalem as a capital based on conditions such as: Palestinian refugees get a chance to return, Palestinian agree on a future truce or peace accord with Israel, although Hamas is not obliged to recognise the state of Israel itself. This offer is significant and has to be seen in the context of the Islamic jurisprudence, which Hamas as a fundamental Islamic movement is bound with. Denying these principles would exclude Hamas from the group of those who take Islam seriously as a political guidance (about the view on Hamas through the lens oft he Islamic jurisprudence see Paul Scham and Osama Abu-Irshaid, “Hamas – Ideological Rigidity and Political Flexibility“).

The Covenant is not the Koran, which is unchangeable. I believe that one day it will be changed or replaced according to the views of the Hamas, in order to realize the national interests of the Palestinians. — Muaman Bseiso, a columnist for the Hamas weekly Al-Risala cited in Aaron D. Pina, “Palestinian Elections“, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, 09.02.2006, p.15.

If the Quartet on the Middle East (the United Nations, the United States, the European Union, and Russia) was eager to take the Islamic jurisprudence into consideration, it could probably find a pragmatic way to work with the PNA, which includes ministers from Hamas. Instead of taking an opportunity after the Parliamentary elections to move to a more moderate stance of Hamas in a long-term, the Quartet refuses to speak with representatives from Hamas and the subsidies for the PNA are bound to requirements. The Quartet members demand to recognise Israel’s right to exist, to renounce violence and to accept previous Israeli-Palestinian agreements. These requirements are justified, but it is very unlikely that Hamas will fulfil all three demands at once.

Nevertheless, since early 2006, suicide attacks have largely ceased, and since the operation “Cast Lead” rocket attacks and mortar shellfire have been significantly reduced. After Israel’s operation, Hamas had to choose if it would follow their armed resistance at all costs or effectively govern the Gaza Strip. If Hamas leaders do not want to lose their legitimacy in the population, they have to do their governmental work in a proper way and give the population a perspective – this will not be possible if Hamas attacks provoke a military retaliation by Israel.

At the same time, the need of legitimacy can be a doubled-edged sword. If the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip have the impression that they cannot improve their social-economical life through political participation, then more violence may return. In this case, Hamas most likely would blame Israel for social-economic failures because Israel’s blockade of goods to the Gaza Strip since June 2007 harms the already crippled Palestinian economy further (cf.: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory, “Easing the Blockade“, Special Focus, March 2011).

With new attacks, Hamas could try to keep their legitimacy as an armed resistance movement among the population. If Hamas does not succeed, it is very likely that people in the Gaza Strip turn to other radical groups like the Palestinian Islamic Jihad or the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades. For all involved parties, the choice between moderation and radicalisation is based on a cost-benefit calculation. On 18th March 2011, Hamas fired more than 30 mortars at Israel and on 7th of April an anti-tank weapon, fired from the Gaza Strip, hit an Israel school bus. These could be reactions on the allegations from hardliners that Hamas lost its way as a resistance movement.

There are concerns that if the status quo holds, the massive unemployment and dispiriting living conditions that have persisted and at points worsened since Israel’s withdrawal in 2005 could contribute to further radicalization of the population, decreasing prospects for peace with Israel and for Palestinian unity and increasing the potential for future violence. — Jim Zanotti, “The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations“, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, 30.08.2011, 14.

Conclusion

Hamas has gained more political responsibility due to the participation and winning the parliamentary elections in 2006, but the question whether it has become more moderate cannot be answered cogently. The decision to participate in the legislative elections is a sign of moderation because the involvement in the PNA would possibly require Hamas to deal with Israel and to engage in political compromises. In the past, the movement used to obstructed the peace process actively, now it indirectly accepts at least the Oslo Accords and is willing for new talks, but on their conditions. Hamas officials use a pragmatic approach and before the elections, they separated the ideological principals from political reality.

The evidences of that are speeches of high-ranking Hamas officials and basic documents like the Hamas elections manifesto. Nevertheless, Hamas did not revoke its Covenant. Its ideological fundament given by an aggressively formulated Covenant does not mean, that Hamas is not able to act reasonably in their political work. In fact, PLO had the same problem with its Palestinian National Covenant, which in several paragraphs calls for the destruction of Israel, but the organisation gave the priority to the political reality. Despite the assurance of Yasser Arafat, PLO’s Covenant was never changed or revoked.

It is a challenge to judge if a change of attitude is really a moderation in the case of the largely ceased suicide attacks since early 2006 and the significantly reduced rocket attacks and mortar shellfire since operation “Cast Lead”. If Hamas does not want to lose its legitimacy in the population, it has to avoid actions, which would provoke a military retaliation by Israel, and it has to improve the life conditions of the population with political means. On the other hand, it is not possible to confute the interpretation of these reduced attacks and say that Hamas stopped them after the operation “Cast Lead” only to rehabilitate itself and to upgrade its military capability (cf.: Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, “Terrorism from the Gaza Strip since Operation Cast Lead – Data, Type and Trends“, 17.03.2011).

The biggest argument against a possible moderation of Hamas attitude is the fact, that Hamas is not willing to renounce violent means to reach its goals. This can be explained with the following reasons: after the elections, Israel and the Quartet on the Middle East did not give Hamas a chance to prove its political capacity and to improve the live of the Palestinian population in the Gaza Strip. Israel’s blockade of goods to the Gaza Strip is standing on the way of improvements of Palestinians daily life. If anything, this blockade could give some security for Israel in the short-term, but such measures could be highly counterproductive in the long-term. Social groups especially turn to violence, if they do not see another option to change their situation, and it is important to offer real political alternatives to improve the people life conditions. With their increased political involvement, Hamas leaders did not see any change for the Palestinians, but they will only renounce violence, sure to reach their goals with political means.

Data sources

- Table 1: American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise, “Major Palestinian Terror Attacks Since Oslo“.

- Table 2: Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, “Terrorism from the Gaza Strip since Operation Cast Lead – Data, Type and Trends“, 17.03.2011.

- Table 3: Palestinian Authority Ministry of Finance, US Government cited in Karen Yourish and Larry Nista, “Falling Short“, The Washington Post, 27.07.2008.