28 dec 2016

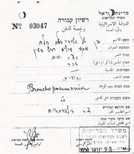

Tzion Salem's 'burial license'

Relatives of babies and toddlers who disappeared mysteriously between 1948 and 1954 fail to find any answers in the released files related the affair. ‘Most of the information is written in unreadable handwriting, and the information that is readable points to a major cover up by the commission of inquiry,’ says Shosh Levy, whose brother went missing at the age of five months.

Shosh Levy of Kfar Saba, whose brother Tzion disappeared at the age of five months, believes the state commission of inquiry into the mysterious disappearance of thousands of Yemenite babies and toddlers between 1948 and 1954 engaged in a “major cover up.”

Along with the relatives of other children who disappeared during those years, Levy read the commission’s documents which were released for the very first time Wednesday, after the decades of public pressure on the government to approve their publication. “A large part of the protocols and investigation materials were written in unreadable handwriting,” she says. “The information that is readable indicates that the commission engaged in a major cover up.”

The published files have opened old wounds and evoked mixed emotions among the families whose children disappeared those years and whose fate is unknown. According to Shosh Levy, after her brother Tzion Salem disappeared, the state claimed that he had died and was buried. “A lot of details in the protocols are inaccurate, to say the least,” she says after reviewing the files. “We saw the death and burial certificate, and it says there that my brother was born on February 29, 1956, was hospitalized on July 22, 1956 and died the next day. That didn’t match the Interior Ministry records."

“There were inaccuracies in regards to his age too,” she claims. “Some of the documents noted that he was hospitalized when he was 18 months old, and others say he was hospitalized at 10 months. My mother insists that he was hospitalized because of a hernia, while the commission’s report says that the reason of hospitalization was malnutrition and diarrhea, although it’s a lie. Moreover, the most important thing is that there is a contradiction between the testimony my mother gave to the commission and the actual testimony written in the protocol. Someone made sure to ‘beautify’ the reality and rewrite the evidence.”

Thousands of personal files have been exposed in the Yemenite children’s affair, but the file about singer Boaz Sharabi’s sister is not among them. Sharabi, who broke into tears at a Knesset discussion half a year ago, explained Wednesday: “We didn’t submit a complaint to the commission, which is why our story wasn’t investigated. We didn’t believe there was a real chance for a serious investigation into the affair.”

Before the protocols were released, Sharabi spoke about the search for his twin sister Ada. “I’m holding onto a shred of optimism although it seems nearly impossible to uncover the truth,” he said. “There are people who are still trying to hide evidence and cover up. There is no doubt that this has opened a Pandora’s box which doesn’t smell very good, to say the least. High-ranking people were involved in this, and the entire public should know who took part in this thing. I appreciate Minister Tzahi Hanegbi and his willingness to release the commission of inquiry’s documents, but he’s a politician and they have one color and one language."

‘I won’t stop searching till my very last day’

Yair Nissan’s older siblings were kidnapped, as far as the family knows, when they were only a few days old. “My emotions are going in both directions,” he says. “First, I am thankful that they opened up the documents for us to see, but I have doubts over what will happen next, whether they’ll open everything and tell us the entire truth. Because this issue is in our soul and blood. It’s my brothers and many children of many families, and we must reach the truth.

“I have the report, I read the report. That’s not the truth. There is no truth in it. My twin siblings were kidnapped,” he stresses.

What does the report you received say?

“They wrote that my brother died on October 1, 1950 and my sister on November 27, 1950, and that doesn’t match the records. My parents arrived in Israel from Iraq, from Baghdad, on September 30, 1950, and two days later the children didn’t feel so good and were sent to the Rambam Medical Center. They were told, ‘You’ll be taken care of and then come back.’ The committee wrote that my brother passed away on October 1, 1950. That’s impossible, he hadn’t arrived yet. I have an Interior Ministry certificate—my parents arrived on September 30 and my siblings arrived on September 15. That doesn’t make sense. There is no such thing. My siblings weren’t born then. They arrived when they were seven days old.”

Nissan points to further inaccuracies that raise doubts. “It’s impossible that I have death certificates from 1972 and 1973 that my siblings passed away. Where were they until then? When I was a soldier, they came to look for my brother. So my father said to them, ‘My son is in the army. Why are you looking here?’ How is it possible that they came to look for him? Till my very last day, till my very last breath, I will not stop. I have a will from my parents.”

‘They’re hiding more than what they’re revealing’

Yaakov Ben Aba from Rehovot lost five siblings, who were allegedly kidnapped – three in 1944 and the other two in 1948 and 1953. “There is nothing new here,” he says. “Opening the protocols to the public is mockery. It’s in order to keep covering up the affair. Instead of opening the adoption files, they are throwing a bone at us in the form of protocols that will not really get us closer to the truth.”

Ben Aba testified at the time before the Kedmi Commission, which released its conclusions in 2001. “It was one big bluff in order to hide the truth from the public,” he says. The commission’s documents state that the family refused to publish the investigation's findings, but Ben Aba denies that.

“At no stage did we object to the publication of the information,” he says. “I no longer recognize this state. It committed a great crime and betrayed us. They are trying to hide more than they’re revealing. I am 64 years old today and I hope I still get to meet my kidnapped siblings, which is something my parents did not get to see.”

‘We saw no bodies and no grave’

Relatives of babies and toddlers who disappeared mysteriously between 1948 and 1954 fail to find any answers in the released files related the affair. ‘Most of the information is written in unreadable handwriting, and the information that is readable points to a major cover up by the commission of inquiry,’ says Shosh Levy, whose brother went missing at the age of five months.

Shosh Levy of Kfar Saba, whose brother Tzion disappeared at the age of five months, believes the state commission of inquiry into the mysterious disappearance of thousands of Yemenite babies and toddlers between 1948 and 1954 engaged in a “major cover up.”

Along with the relatives of other children who disappeared during those years, Levy read the commission’s documents which were released for the very first time Wednesday, after the decades of public pressure on the government to approve their publication. “A large part of the protocols and investigation materials were written in unreadable handwriting,” she says. “The information that is readable indicates that the commission engaged in a major cover up.”

The published files have opened old wounds and evoked mixed emotions among the families whose children disappeared those years and whose fate is unknown. According to Shosh Levy, after her brother Tzion Salem disappeared, the state claimed that he had died and was buried. “A lot of details in the protocols are inaccurate, to say the least,” she says after reviewing the files. “We saw the death and burial certificate, and it says there that my brother was born on February 29, 1956, was hospitalized on July 22, 1956 and died the next day. That didn’t match the Interior Ministry records."

“There were inaccuracies in regards to his age too,” she claims. “Some of the documents noted that he was hospitalized when he was 18 months old, and others say he was hospitalized at 10 months. My mother insists that he was hospitalized because of a hernia, while the commission’s report says that the reason of hospitalization was malnutrition and diarrhea, although it’s a lie. Moreover, the most important thing is that there is a contradiction between the testimony my mother gave to the commission and the actual testimony written in the protocol. Someone made sure to ‘beautify’ the reality and rewrite the evidence.”

Thousands of personal files have been exposed in the Yemenite children’s affair, but the file about singer Boaz Sharabi’s sister is not among them. Sharabi, who broke into tears at a Knesset discussion half a year ago, explained Wednesday: “We didn’t submit a complaint to the commission, which is why our story wasn’t investigated. We didn’t believe there was a real chance for a serious investigation into the affair.”

Before the protocols were released, Sharabi spoke about the search for his twin sister Ada. “I’m holding onto a shred of optimism although it seems nearly impossible to uncover the truth,” he said. “There are people who are still trying to hide evidence and cover up. There is no doubt that this has opened a Pandora’s box which doesn’t smell very good, to say the least. High-ranking people were involved in this, and the entire public should know who took part in this thing. I appreciate Minister Tzahi Hanegbi and his willingness to release the commission of inquiry’s documents, but he’s a politician and they have one color and one language."

‘I won’t stop searching till my very last day’

Yair Nissan’s older siblings were kidnapped, as far as the family knows, when they were only a few days old. “My emotions are going in both directions,” he says. “First, I am thankful that they opened up the documents for us to see, but I have doubts over what will happen next, whether they’ll open everything and tell us the entire truth. Because this issue is in our soul and blood. It’s my brothers and many children of many families, and we must reach the truth.

“I have the report, I read the report. That’s not the truth. There is no truth in it. My twin siblings were kidnapped,” he stresses.

What does the report you received say?

“They wrote that my brother died on October 1, 1950 and my sister on November 27, 1950, and that doesn’t match the records. My parents arrived in Israel from Iraq, from Baghdad, on September 30, 1950, and two days later the children didn’t feel so good and were sent to the Rambam Medical Center. They were told, ‘You’ll be taken care of and then come back.’ The committee wrote that my brother passed away on October 1, 1950. That’s impossible, he hadn’t arrived yet. I have an Interior Ministry certificate—my parents arrived on September 30 and my siblings arrived on September 15. That doesn’t make sense. There is no such thing. My siblings weren’t born then. They arrived when they were seven days old.”

Nissan points to further inaccuracies that raise doubts. “It’s impossible that I have death certificates from 1972 and 1973 that my siblings passed away. Where were they until then? When I was a soldier, they came to look for my brother. So my father said to them, ‘My son is in the army. Why are you looking here?’ How is it possible that they came to look for him? Till my very last day, till my very last breath, I will not stop. I have a will from my parents.”

‘They’re hiding more than what they’re revealing’

Yaakov Ben Aba from Rehovot lost five siblings, who were allegedly kidnapped – three in 1944 and the other two in 1948 and 1953. “There is nothing new here,” he says. “Opening the protocols to the public is mockery. It’s in order to keep covering up the affair. Instead of opening the adoption files, they are throwing a bone at us in the form of protocols that will not really get us closer to the truth.”

Ben Aba testified at the time before the Kedmi Commission, which released its conclusions in 2001. “It was one big bluff in order to hide the truth from the public,” he says. The commission’s documents state that the family refused to publish the investigation's findings, but Ben Aba denies that.

“At no stage did we object to the publication of the information,” he says. “I no longer recognize this state. It committed a great crime and betrayed us. They are trying to hide more than they’re revealing. I am 64 years old today and I hope I still get to meet my kidnapped siblings, which is something my parents did not get to see.”

‘We saw no bodies and no grave’

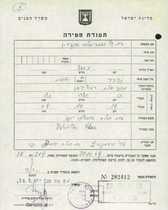

Death certificate of the Danin triplets

Meir Danin, who says three of his siblings were kidnapped, is skeptical. “I believe there are documents that will never be published. I have no doubt that in most cases documents and evidence were concealed, so the information that is being exposed now is already covered up.”

His mother, the late Hamama Danin, immigrated to Israel in 1949 and gave birth to triplets about a month later in the tent they were housed in. “She and the children were taken to the Djani Hospital in Jaffa. My mother was discharged and they told her at the hospital that the babies would be released later on, but to this very day we still don’t know what happened to the three of them. We saw no bodies and no grave.”

When did Zohara die?

Meir Danin, who says three of his siblings were kidnapped, is skeptical. “I believe there are documents that will never be published. I have no doubt that in most cases documents and evidence were concealed, so the information that is being exposed now is already covered up.”

His mother, the late Hamama Danin, immigrated to Israel in 1949 and gave birth to triplets about a month later in the tent they were housed in. “She and the children were taken to the Djani Hospital in Jaffa. My mother was discharged and they told her at the hospital that the babies would be released later on, but to this very day we still don’t know what happened to the three of them. We saw no bodies and no grave.”

When did Zohara die?

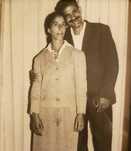

Moti Dahbash's parents. Were told that their daughter had died

Moti Dahbash testified before the Kedmi Commission in 2001. According to the commission’s protocols, two weeks after his parents immigrated to Israel, his two-year-old sister Zohara was taken to the babies’ home in Rosh Ha’ayin because she was suffering from diarrhea, which he says is a lie. Several days later, when they came to visit her, they were told by the staff that Zohara had died. When the mother asked to see her body, she was told that the girl had already been buried and that her place of burial was unknown.

The commission of inquiry’s conclusions reveal an inconsistency in the records of Zohara’s death. According to death log book of the Jewish Agency, which paid for Zohara’s burial, she passed away at the age of nine. The commission determined that there was a mistake in recording of the information and that she had died at the age of two, several days after being hospitalized.

“I have a little hope, but also a very great fear that nothing will come out of this,” Dahbash says. “So many questions are still left unanswered, and the protocols won’t provide any answers either. There are senior political elements that are still trying to cover up details of the affair. There is no escape from reaching the truth once and for all. We won’t give up until we know where they have all disappeared to.”

Knesset Member Nurit Koren (Likud), head of the Lobby for Researching the Truth in the Kidnapped Yemenite Children Affair, has no intention of letting go. “I have established a DNA database together with the My Heritage company, submitted two bills and worked to open the protocols that are being released to the public today,” she says.

“I welcome the release of the protocols after months of fighting to expose the truth. I am doing this with all my heart. I have been losing sleep over these stories, and beyond the children who were kidnapped from my own family, I feel committed to all the families as if they were my own.

“The release of the protocols is the first layer in exposing the truth. The next stage is establishing a special Knesset committee that will compile all the evidence and provide answers to the thousands of families, including many elderly people who are unable to find answers on the website.

“In addition, my office has received new complaints and evidence which did not reach the previous commission of inquiry. They must be investigated, and the families must receive real answers once and for all.”

Moti Dahbash testified before the Kedmi Commission in 2001. According to the commission’s protocols, two weeks after his parents immigrated to Israel, his two-year-old sister Zohara was taken to the babies’ home in Rosh Ha’ayin because she was suffering from diarrhea, which he says is a lie. Several days later, when they came to visit her, they were told by the staff that Zohara had died. When the mother asked to see her body, she was told that the girl had already been buried and that her place of burial was unknown.

The commission of inquiry’s conclusions reveal an inconsistency in the records of Zohara’s death. According to death log book of the Jewish Agency, which paid for Zohara’s burial, she passed away at the age of nine. The commission determined that there was a mistake in recording of the information and that she had died at the age of two, several days after being hospitalized.

“I have a little hope, but also a very great fear that nothing will come out of this,” Dahbash says. “So many questions are still left unanswered, and the protocols won’t provide any answers either. There are senior political elements that are still trying to cover up details of the affair. There is no escape from reaching the truth once and for all. We won’t give up until we know where they have all disappeared to.”

Knesset Member Nurit Koren (Likud), head of the Lobby for Researching the Truth in the Kidnapped Yemenite Children Affair, has no intention of letting go. “I have established a DNA database together with the My Heritage company, submitted two bills and worked to open the protocols that are being released to the public today,” she says.

“I welcome the release of the protocols after months of fighting to expose the truth. I am doing this with all my heart. I have been losing sleep over these stories, and beyond the children who were kidnapped from my own family, I feel committed to all the families as if they were my own.

“The release of the protocols is the first layer in exposing the truth. The next stage is establishing a special Knesset committee that will compile all the evidence and provide answers to the thousands of families, including many elderly people who are unable to find answers on the website.

“In addition, my office has received new complaints and evidence which did not reach the previous commission of inquiry. They must be investigated, and the families must receive real answers once and for all.”

After decades of pressure placed on the government to release files pertaining to the fate of thousands of Yemenite children, who went missing between 1948-1954, researchers and families can now examine 210,000 documents on the web, shedding light on where the children went and how they eventually died.

The Israel National Archives declassified Wednesday 3,500 files relating to the Yemenite children affair— the mysterious disappearance of thousands of Yemenite babies and toddlers between 1948 and 1954.

The files contain 210,000 documents which can be accessed on the archive’s website, and will now enable family members to finally learn the fate of thousands of children, while researchers will be able to enter into personal files, examine where they were buried and their causes of death.

The Yemenite Children affair resurfaced once again in the public debate in May this year following the Achim Vekayamim organization’s stated intention to renew efforts to discover the truth behind one of the cases, which has caused a storm in Israel for decades.

The Israel National Archives declassified Wednesday 3,500 files relating to the Yemenite children affair— the mysterious disappearance of thousands of Yemenite babies and toddlers between 1948 and 1954.

The files contain 210,000 documents which can be accessed on the archive’s website, and will now enable family members to finally learn the fate of thousands of children, while researchers will be able to enter into personal files, examine where they were buried and their causes of death.

The Yemenite Children affair resurfaced once again in the public debate in May this year following the Achim Vekayamim organization’s stated intention to renew efforts to discover the truth behind one of the cases, which has caused a storm in Israel for decades.

Documents on missing children

Due to public pressure, Minister in the Prime Minister's Office Tzahi Hanegbi, appointed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, was ordered to recommend that the government remove most of the confidentiality and open the protocols of the Cohen-Kedmi Committee, charged with investigating the Yemenite children affair and upload them to the internet.

During a special press conference held by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he described the development as a “correction of injustice.”

“We are fixing today an historic injustice, of ignoring, of disappearance and of discrimination," Netanyahu declared. “We don’t know what the fate was of the Yemenite children. Close to 60 years people have not know of the fate of their children. We are not prepared for this to continue which is why we decided on transparency and justice.”

Three committees were set up to look into the scandal to investigate 1,033 incidents of which the Cohen-Kedmi Committee concluded that 972 babies had died and 56 had remained anonymous. The committee’s conclusions were published in 2001.

The committee rejected claims that the children had gone missing as a result of institutionalized kidnappings of children but did deduce from the information at its disposal that during the same period, there was “the occasional delivery of babies for adoption from kindergartens and and hospitals.”

The research of the adoption files which have now been declassified also shed light on the process of adoption in Israel during the 50s. However, the names of the children are concealed in accordance with the law.

Indeed, one of the files contains information about a girl born in 1950 who “was taken care of in a kindergarten by the welfare office of Tiberias.” In the file it is written, “The mother went missing and all efforts to find her were to no avail.” What efforts were undertaken? According to the document, an ad was published in the Davar newspaper.

The documents record another incident in which a baby girl was brought by her mother to a kindergarten and only one year later were attempts made to find her parents who did not come back. They were nowhere to be found. Similar to the previous case, just an advert was published in the Davar.

In 1954, the files reveal that a young girl was put up for adoption for a couple of Holocaust survivors after it was claimed that her mother had left Israel and her father’s whereabouts was unknown. The girl was delivered by a private broker, who also left Israel, and the new parents, claimed that they knew nothing of the child's past or the identity of her parents.

In this case, the file contains the following commentary: “It is inconceivable that the applicants took the child without a birth certificate or other material that proves the identity.”

According to documents submitted to the Cohen-Kedmi Committee by Attorney Drora Nehami-Ruth, in 1952 adoption from hospitals was a commonplace phenomenon. It involved brokers and the doctors themselves.

“This was a case of unauthorized conduct by public hospitals in delivering children who were born within their walls to all kinds of people for the purpose of adoption,” the legal advisor wrote. “I don’t want to expand on this, how easy it was to take advantage of the possibility of delivering children born outside of wedlock to people who would knock on the hospital doors in exchange for something.”

Due to public pressure, Minister in the Prime Minister's Office Tzahi Hanegbi, appointed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, was ordered to recommend that the government remove most of the confidentiality and open the protocols of the Cohen-Kedmi Committee, charged with investigating the Yemenite children affair and upload them to the internet.

During a special press conference held by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he described the development as a “correction of injustice.”

“We are fixing today an historic injustice, of ignoring, of disappearance and of discrimination," Netanyahu declared. “We don’t know what the fate was of the Yemenite children. Close to 60 years people have not know of the fate of their children. We are not prepared for this to continue which is why we decided on transparency and justice.”

Three committees were set up to look into the scandal to investigate 1,033 incidents of which the Cohen-Kedmi Committee concluded that 972 babies had died and 56 had remained anonymous. The committee’s conclusions were published in 2001.

The committee rejected claims that the children had gone missing as a result of institutionalized kidnappings of children but did deduce from the information at its disposal that during the same period, there was “the occasional delivery of babies for adoption from kindergartens and and hospitals.”

The research of the adoption files which have now been declassified also shed light on the process of adoption in Israel during the 50s. However, the names of the children are concealed in accordance with the law.

Indeed, one of the files contains information about a girl born in 1950 who “was taken care of in a kindergarten by the welfare office of Tiberias.” In the file it is written, “The mother went missing and all efforts to find her were to no avail.” What efforts were undertaken? According to the document, an ad was published in the Davar newspaper.

The documents record another incident in which a baby girl was brought by her mother to a kindergarten and only one year later were attempts made to find her parents who did not come back. They were nowhere to be found. Similar to the previous case, just an advert was published in the Davar.

In 1954, the files reveal that a young girl was put up for adoption for a couple of Holocaust survivors after it was claimed that her mother had left Israel and her father’s whereabouts was unknown. The girl was delivered by a private broker, who also left Israel, and the new parents, claimed that they knew nothing of the child's past or the identity of her parents.

In this case, the file contains the following commentary: “It is inconceivable that the applicants took the child without a birth certificate or other material that proves the identity.”

According to documents submitted to the Cohen-Kedmi Committee by Attorney Drora Nehami-Ruth, in 1952 adoption from hospitals was a commonplace phenomenon. It involved brokers and the doctors themselves.

“This was a case of unauthorized conduct by public hospitals in delivering children who were born within their walls to all kinds of people for the purpose of adoption,” the legal advisor wrote. “I don’t want to expand on this, how easy it was to take advantage of the possibility of delivering children born outside of wedlock to people who would knock on the hospital doors in exchange for something.”

14 nov 2016

|

|

A Jewish mother who emigrated to Israel from Morocco in 1948 was told her baby died at childbirth but she believes her son was alive and given away.

CNN's Oren Liebermann reports. |

12 nov 2016

Hundreds of thousands of documents relating to the disappearance of thousands of Yemenite children during the founding of the state are to be released on Sunday.

After decades of struggling, the public may finally be able to have access to documents which deal with the investigations into the disappearance of thousands of Yemenite child immigrants on Sunday.

These children along with children, whose families originate in Muslim countries in the Middle East and the Balkans, went missing during the first years of the State of Israel.

Minister Tzahi Hanegbi will submit a proposal on the issue. As long as there are no last-minute roadblocks, hundreds of thousands of documents will be brought to light regarding this tragic period wherein thousands of children were allegedly kidnapped from their parents.

The minister is expected to request the government to put all of the documents on an internet site so that they will be easily accessible and so that the suffering of these families will finally come to an end.

The draft resolution indicated that the public interest must be taken into account when exposing these documents. This, in conjunction with court orders regarding the protection of privacy, and other secrets.

Several of the documents related to the issue won't be allowed to be published due to national security issues and personal privacy laws.

After decades of struggling, the public may finally be able to have access to documents which deal with the investigations into the disappearance of thousands of Yemenite child immigrants on Sunday.

These children along with children, whose families originate in Muslim countries in the Middle East and the Balkans, went missing during the first years of the State of Israel.

Minister Tzahi Hanegbi will submit a proposal on the issue. As long as there are no last-minute roadblocks, hundreds of thousands of documents will be brought to light regarding this tragic period wherein thousands of children were allegedly kidnapped from their parents.

The minister is expected to request the government to put all of the documents on an internet site so that they will be easily accessible and so that the suffering of these families will finally come to an end.

The draft resolution indicated that the public interest must be taken into account when exposing these documents. This, in conjunction with court orders regarding the protection of privacy, and other secrets.

Several of the documents related to the issue won't be allowed to be published due to national security issues and personal privacy laws.

14 aug 2016

Hannah and Shmuel London's son was kept in the hospital, next time they came they were told he had died, but no proof was provided.

It was always known that roughly a thousand of Yemenite children disappeared in the 50s, but Haaretz report has revealed Ashkenazi children 'disappeared' as well. Now, in wake of report, new families have come forward.

Some 40 Ashkenazi families contacted Haaretz over the weekend to reveal that their children had disappeared from hospitals in Israel in the 1940s and 1950s — a phenomenon which until recently was thought to have been largely limited to immigrants from Yemen.

The Ashkenazi families were responding to an investigative report in Haaretz on Friday about other Ashkenazi babies who vanished in the early years of the state.

Some of the families who reacted to the article wanted readers to know their full stories, while others wished to make known that they, too, were victims of similar circumstances but preferred not to go public with their experiences. Haaretz documented half of these testimonies.

Among them are Jews who came from Lithuania, Austria, Poland, Hungary, Romania and Ukraine, including a number of Holocaust survivors.

All of them told similar stories about their babies who had disappeared from various hospitals in Israel. All were told that their infants had died, but were never shown either a death certificate or a grave.

These 20 cases come in the wake of dozens of other instances documented by Haaretz over the past few weeks. They show that the scope of the phenomenon of disappeared children born to Ashkenazi families is wider than previously described by the state investigative committee that examined the cases of disappeared Yemenite babies.

That report, released in 2001, included only 30 cases of children from the United States or Europe who were said to have disappeared soon after birth, as opposed to hundreds of cases of children born to Yemenite families.

Some of the cases Haaretz learned about over the weekend involve twins, one of whom vanished after birth. Such is the story of the London family from Lithuania. The mother, Hannah, came to live in Israel in 1933 as a pioneer and a member of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. The father, Shmuel, came to Israel the same year. The two met in Ramat Gan and were married in 1939. On December 17, 1940, their twins, Avraham and Yaakov, were born at Beilinson Hospital in Petah Tikvah.

“Yaakov came back with mother from the hospital. Avraham stayed ‘to get stronger.’ My mother was told he was born smaller and it was better for him to stay in the hospital,” their daughter, who asked that her name not be publicized, said. Later, when the parents went back to the hospital to take Avraham home, they were told that he had died while being fed.

“They never received a document about it,” the daughter said. “My mother accepted what they told her, and later told this story as an anecdote, not as something special,” she added. “Maybe he really did die, but it’s still interesting to find out what happened,” she said.

The family’s tragedy did not end there. Yaakov, who eventually obtained a Ph.D. in biochemistry, was killed in the Yom Kippur War, leaving a wife and two daughters.

“It’s important to know that cases like these happened even before the establishment of the state. It happened to us,” she said.

Documentation of a disappearance from a hospital in 1940 is rare. Most of the cases happened in the first years following the establishment of the state. One case, documented by this reporter, involved the disappearance of a baby born in the detention camp in Cyprus in 1947.

Yitzhak Fueurstein also turned to Haaretz over the weekend. He is the son of Holocaust survivors Pirha (Piri), born in Transylvania (a region between Romania and Hungary) and Binyamin, born in Munkatch (then Czechoslovakia, now Ukraine). Fueurstein’s parents met in Germany as refugees and came to live in Israel in 1947 after being expelled from the British detention camp on Cyprus.

In 1949 Piri gave birth to twin boys at Rambam Hospital in Haifa. “The birth was normal according to my parents,” Fueurstein said. But about a week later, when his mother was released from the hospital, the parents were given a birth certificate on which the two births appeared, but next to one was the word “deceased.” They were given no other document or death certificate, Fueurstein said.

“The story hovered around our household all the time, leaving many questions in the air,” he added.

It was always known that roughly a thousand of Yemenite children disappeared in the 50s, but Haaretz report has revealed Ashkenazi children 'disappeared' as well. Now, in wake of report, new families have come forward.

Some 40 Ashkenazi families contacted Haaretz over the weekend to reveal that their children had disappeared from hospitals in Israel in the 1940s and 1950s — a phenomenon which until recently was thought to have been largely limited to immigrants from Yemen.

The Ashkenazi families were responding to an investigative report in Haaretz on Friday about other Ashkenazi babies who vanished in the early years of the state.

Some of the families who reacted to the article wanted readers to know their full stories, while others wished to make known that they, too, were victims of similar circumstances but preferred not to go public with their experiences. Haaretz documented half of these testimonies.

Among them are Jews who came from Lithuania, Austria, Poland, Hungary, Romania and Ukraine, including a number of Holocaust survivors.

All of them told similar stories about their babies who had disappeared from various hospitals in Israel. All were told that their infants had died, but were never shown either a death certificate or a grave.

These 20 cases come in the wake of dozens of other instances documented by Haaretz over the past few weeks. They show that the scope of the phenomenon of disappeared children born to Ashkenazi families is wider than previously described by the state investigative committee that examined the cases of disappeared Yemenite babies.

That report, released in 2001, included only 30 cases of children from the United States or Europe who were said to have disappeared soon after birth, as opposed to hundreds of cases of children born to Yemenite families.

Some of the cases Haaretz learned about over the weekend involve twins, one of whom vanished after birth. Such is the story of the London family from Lithuania. The mother, Hannah, came to live in Israel in 1933 as a pioneer and a member of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. The father, Shmuel, came to Israel the same year. The two met in Ramat Gan and were married in 1939. On December 17, 1940, their twins, Avraham and Yaakov, were born at Beilinson Hospital in Petah Tikvah.

“Yaakov came back with mother from the hospital. Avraham stayed ‘to get stronger.’ My mother was told he was born smaller and it was better for him to stay in the hospital,” their daughter, who asked that her name not be publicized, said. Later, when the parents went back to the hospital to take Avraham home, they were told that he had died while being fed.

“They never received a document about it,” the daughter said. “My mother accepted what they told her, and later told this story as an anecdote, not as something special,” she added. “Maybe he really did die, but it’s still interesting to find out what happened,” she said.

The family’s tragedy did not end there. Yaakov, who eventually obtained a Ph.D. in biochemistry, was killed in the Yom Kippur War, leaving a wife and two daughters.

“It’s important to know that cases like these happened even before the establishment of the state. It happened to us,” she said.

Documentation of a disappearance from a hospital in 1940 is rare. Most of the cases happened in the first years following the establishment of the state. One case, documented by this reporter, involved the disappearance of a baby born in the detention camp in Cyprus in 1947.

Yitzhak Fueurstein also turned to Haaretz over the weekend. He is the son of Holocaust survivors Pirha (Piri), born in Transylvania (a region between Romania and Hungary) and Binyamin, born in Munkatch (then Czechoslovakia, now Ukraine). Fueurstein’s parents met in Germany as refugees and came to live in Israel in 1947 after being expelled from the British detention camp on Cyprus.

In 1949 Piri gave birth to twin boys at Rambam Hospital in Haifa. “The birth was normal according to my parents,” Fueurstein said. But about a week later, when his mother was released from the hospital, the parents were given a birth certificate on which the two births appeared, but next to one was the word “deceased.” They were given no other document or death certificate, Fueurstein said.

“The story hovered around our household all the time, leaving many questions in the air,” he added.

Yosef Raflenski, born October 8, 1948 in Tel Aviv. At age six weeks his twin brother Israel was taken to the hospital. The next day, his parents were told Israel had died.

Twins Israel and Yosef, the sons of Holocaust survivors Moshe and Regina (Rivka) Raflenski, were born on October 8, 1948 in Hadassah Hospital, which was then in Tel Aviv. At six weeks old Israel he was rushed to the hospital with diarrhea. His parents — who had come to Israel from Poland — were told to leave their sick son there and go home. When they came to visit him the next day, they were told that he had died.

“His mother called him Israel in the hope of new life in the land of Israel. He never had a funeral, no death certificate was ever presented and of course, he has no grave,” the daughter of Yosef, Israel’s brother, said. She also asked that her name not be used.

Then, one day the family received a draft notice for Israel, which stated that he was a deserter. “All through the years his status in the Interior Ministry was defined as “unknown.” Recently I found out that his status was changed to ‘deceased.’ We are trying, without success, to find out any sliver of information about the lost son,” she added.

“The article in Haaretz on Friday opened up a new wound,” Hannah Gold Levkovich said. Her mother, Shulamit Denishevsky, was born in the town of Ashmyany, near the Lithuanian city of Vilnius. Her father, Yehoshua Gold, was born in the city of Ropczyce, near Krakow in Poland. They met after World War II in a displaced persons camp in Germany, and married.

In 1948, after the state was founded, they came to live in Israel. In the summer of 1949 they had a son at the Dajani (Tzahalon) Hospital in Jaffa. “The birth was normal. The child was big and healthy, but he was taken away immediately,” Levkovich told Haaretz over the weekend. A few hours later they were told their son had died. “They were shown no proof,” Levkovich said.

“All the years my parents claimed the boy was alive, but unfortunately my sister Tova and I did not go along with this terrible thought,” she added. “My parents were Holocaust survivors who had lost everything dear to them in the war and they both suffered, each separately, the hardships of the war. They came to the Promised Land and did not believe such a thing could happen to them.”

Twins Israel and Yosef, the sons of Holocaust survivors Moshe and Regina (Rivka) Raflenski, were born on October 8, 1948 in Hadassah Hospital, which was then in Tel Aviv. At six weeks old Israel he was rushed to the hospital with diarrhea. His parents — who had come to Israel from Poland — were told to leave their sick son there and go home. When they came to visit him the next day, they were told that he had died.

“His mother called him Israel in the hope of new life in the land of Israel. He never had a funeral, no death certificate was ever presented and of course, he has no grave,” the daughter of Yosef, Israel’s brother, said. She also asked that her name not be used.

Then, one day the family received a draft notice for Israel, which stated that he was a deserter. “All through the years his status in the Interior Ministry was defined as “unknown.” Recently I found out that his status was changed to ‘deceased.’ We are trying, without success, to find out any sliver of information about the lost son,” she added.

“The article in Haaretz on Friday opened up a new wound,” Hannah Gold Levkovich said. Her mother, Shulamit Denishevsky, was born in the town of Ashmyany, near the Lithuanian city of Vilnius. Her father, Yehoshua Gold, was born in the city of Ropczyce, near Krakow in Poland. They met after World War II in a displaced persons camp in Germany, and married.

In 1948, after the state was founded, they came to live in Israel. In the summer of 1949 they had a son at the Dajani (Tzahalon) Hospital in Jaffa. “The birth was normal. The child was big and healthy, but he was taken away immediately,” Levkovich told Haaretz over the weekend. A few hours later they were told their son had died. “They were shown no proof,” Levkovich said.

“All the years my parents claimed the boy was alive, but unfortunately my sister Tova and I did not go along with this terrible thought,” she added. “My parents were Holocaust survivors who had lost everything dear to them in the war and they both suffered, each separately, the hardships of the war. They came to the Promised Land and did not believe such a thing could happen to them.”