14 may 2013

FACT SHEET: THE NAKBA: 65 YEARS OF DISPOSSESSION & APARTHEID

Jews of Peki'in, Palestine, c. 1930.

1) Prelude to Disaster

a. The Emergence of Political Zionism, Conflict Between Early Zionist Colonists & Palestinian Arabs, & "Transfer" (Late 19th, Early 20th Century)

b. World War I: The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence & The Balfour Declaration (1914-1918)

c. The British Mandate for Palestine (1923-1948)

d. The Arab Revolt in Palestine (1936-1939)

e. The Irgun & Lehi: Zionist Terrorism on the Rise (1937-1948)

f. World War II & The Holocaust (1939-1945)

2) The Nakba: Creating Israel on the Ruins of Palestine

a. The United Nations Partition Plan (November 1947)

b. Beginnings of Civil War & Ethnic Cleansing (December 1947-May 1948)

c. British Withdrawal, Israeli Independence, & The Arab-Israeli War of 1948 (May 1948-March 1949)

d. Massacres & Atrocities Against Palestinian Civilians

e. Palestinian Refugees & The Right of Return

f. Palestinian Population Centers Systematically Destroyed or Repopulated with Jewish Immigrants, Stolen & Destroyed Property

3) The Ongoing Nakba: 1948 to Present

a. Palestinians Who Remained Inside Israel

b. The June 1967 War: The Nakba Redux

c. Post-1967: Occupation, Settlements, Walls, & Apartheid

4) Further References

1. PRELUDE TO DISASTER

"We shall try to spirit the penniless [Palestinian] population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country... expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly." - Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism.

1) Prelude to Disaster

a. The Emergence of Political Zionism, Conflict Between Early Zionist Colonists & Palestinian Arabs, & "Transfer" (Late 19th, Early 20th Century)

b. World War I: The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence & The Balfour Declaration (1914-1918)

c. The British Mandate for Palestine (1923-1948)

d. The Arab Revolt in Palestine (1936-1939)

e. The Irgun & Lehi: Zionist Terrorism on the Rise (1937-1948)

f. World War II & The Holocaust (1939-1945)

2) The Nakba: Creating Israel on the Ruins of Palestine

a. The United Nations Partition Plan (November 1947)

b. Beginnings of Civil War & Ethnic Cleansing (December 1947-May 1948)

c. British Withdrawal, Israeli Independence, & The Arab-Israeli War of 1948 (May 1948-March 1949)

d. Massacres & Atrocities Against Palestinian Civilians

e. Palestinian Refugees & The Right of Return

f. Palestinian Population Centers Systematically Destroyed or Repopulated with Jewish Immigrants, Stolen & Destroyed Property

3) The Ongoing Nakba: 1948 to Present

a. Palestinians Who Remained Inside Israel

b. The June 1967 War: The Nakba Redux

c. Post-1967: Occupation, Settlements, Walls, & Apartheid

4) Further References

1. PRELUDE TO DISASTER

"We shall try to spirit the penniless [Palestinian] population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country... expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly." - Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism.

In the centuries prior to the rise of political Zionism in Europe in the late 19th century, relations between the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish communities in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire, were relatively good. While there was occasional conflict, compared to the anti-Semitism and persecution Jews faced in Europe, the Ottoman Empire and the Arab-Muslim worlds were a haven.

The British Mandate for Palestine (1923-1948)

The Irgun & Lehi: Zionist Terrorism on the Rise (1937-1948)

2. THE NAKBA: CREATING ISRAEL ON THE RUINS OF PALESTINE

- In the mid-19th century, influenced by the nationalism then sweeping much of the continent, some European Jews concluded that the remedy to centuries of persecution and pogroms in Europe and Russia was the creation of a nation state for Jews in Palestine. Some of them subsequently began emigrating to the Holy Land. In 1874, [PDF] there were about 14,000 Jews in Palestine, and about 426,000 Arabs.

- In 1896, Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl, considered the father of modern political Zionism, catalyzed the movement with the publication of "The Jewish State." The following year Herzl was elected president of the First Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland.

- As they arrived in Palestine, early Zionist settlers inevitably came into conflict with the native Palestinian Arab population, particularly small tenant farmers known as fellahin. These peasant farmers were often dispossessed from lands their families had worked for generations to make way for colonies established by European Jews who intended to "redeem" the land through the use of Jewish labor.

- A key actor in the dispossession of Palestinians was the Jewish National Fund (JNF), founded in 1901 at the Fifth Zionist Congress. It was tasked with acquiring land for the Zionist enterprise in Palestine, frequently purchasing [PDF] it from large Ottoman Turkish landowners who lived abroad. The quasi-governmental Jewish National Fund continues to play an important role in the distribution of state lands and the ongoing dispossession of Palestinians in Israel today, denying non-Jewish citizens access to the 13% of state lands it controls directly, and the 93% total overall its leadership has sway over via the Israel Lands Authority. Its mission statement declares: "The Jewish National Fund is the caretaker of the land of Israel, on behalf of its owners - Jewish people everywhere."

- In 1903, there were approximately 25,000 Jews in Palestine, and about 500,000 Arabs.

- From the earliest days of the movement, Zionist leaders struggled with the dilemma of how to deal with the non-Jewish Palestinians who inhabited the land on which they wanted to create their state. Most, including Herzl, concluded the only solution was what became known as "transfer," a euphemism for what is known as "ethnic cleansing" today.

- In June 1895 Herzl wrote in his diary: "We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country... expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly."

- In August 1937, transfer was discussed at the Twentieth Zionist Congress in Zurich, Switzerland. Alluding to the systematic dispossession of Palestinian peasant farmers that Zionist colonists had been engaged in for decades, the leader of the Zionist community in Palestine (the Yishuv) and Israel's first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, stated:"You are no doubt aware of the JNF's activity in this respect. Now a transfer of a completely different scope will have to be carried out. In many parts of the country new settlement will not be possible without transferring the Arab fellahin." He added: "Jewish power [in Palestine], which grows steadily, will also increase our possibilities to carry out this transfer on a large scale."

- In an October 1937 letter to his son, Amos, Ben-Gurion wrote: [PDF] "We must expel Arabs and take their place."

- In June 1938, transfer was the major focus of a meeting of the Jewish Agency Executive, the de facto government of the Yishuv. Arthur Ruppin, head of the Jewish Agency from 1933 to 1935 and one of the founders of Tel Aviv, declared: "I do not believe in the transfer of individuals. I believe in the transfer of entire villages." Ben-Gurion argued in favor of transfer as well, stating: "With compulsory transfer we [would] have a vast area [for settlement]... I support compulsory transfer. I don't see anything immoral in it."

- Summing up the feelings of many Zionist leaders, in December 1940, Joseph Weitz, director of the Jewish National Fund's Lands Department and a strong advocate of transfer wrote in his diary:

"There is no way besides transferring the Arabs from here to the neighboring countries, and to transfer all of them, save perhaps for [the Arabs of] Bethlehem, Nazareth and Old Jerusalem. Not one village must be left, not one [Bedouin] tribe. And only after this transfer will the country be able to absorb millions of our brothers and the Jewish problem will cease to exist. There is no other solution." - While Zionist leaders debated transfer behind closed doors, in public they were careful to avoid mention of it. As Israeli historian Benny Morris noted in the follow up to his landmark 1989 work, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (2004):

"All understood that discretion and circumspection were called for: Talk of transferring the Arabs, even with Palestinian and outside Arab leaders' agreement, would only put them on their guard and antagonize them, and quite probably needlessly antagonize the Arabs' Ottoman coreligionists, who ruled the country." - Regarding Ben-Gurion, Morris, himself a right-wing Zionist who has lamented that the expulsions of the Nakba didn't go far enough, noted: "Ben Gurion always refrained from issuing clear or written expulsion orders; he preferred that his generals 'understand' what he wanted done. He wished to avoid going down in history as the 'great expeller.'"

- The dispossession of Palestinians in order to create and maintain a Jewish majority state in the heart of the Arab and Muslim Middle East was and remains the underlying cause of the Israeli-Palestinian and larger Arab-Israeli conflict. Today, senior Israeli political and religious leaders continue to advocate expulsion and "transfer" of Palestinian citizens as well as Palestinians living under Israeli military rule in the occupied territories.

"Transfer"

- During World War I (1914-1918), the Middle East became a battleground, with Britain and its allies seeking to undermine the rule of the Ottoman Empire in the region. In the course of the war, the British government made promises to both Arabs and Zionist Jews regarding the future of Palestine.

- Between July 1915 and January 1916, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, and Sharif Hussein bin Ali of the city of Mecca, exchanged a series of letters in which the British government promised to support the creation of an independent Arab state in the Middle East, including Palestine, in exchange for the launching of an Arab rebellion against Ottoman rule. Their letters became known as the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence.

- Almost immediately after concluding an agreement with Hussein, in May 1916 the British signed a secret pact with France, the Sykes-Picot Agreement, to divvy up much of the Middle East, including the region of Palestine, into English and French colonial protectorates following the war.

- In what appeared to be another blatant contradiction of the commitment made to the Arabs in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, in November 1917 British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour sent a letter to Baron Rothschild, a leader of the Jewish community in Britain, endorsing the creation of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. The Balfour Declaration was a major diplomatic victory for Zionist leaders, who sought the patronage of a great power to realize their plans.

- In 1922, the United States government released the results of an official investigation conducted three years earlier on the situation in Palestine and other areas of the former Ottoman Empire. In commenting on the Balfour Declaration, the King-Crane Commission Report noted:

"For 'a national home for the Jewish people' is not equivalent to making Palestine into a Jewish State; nor can the erection of such a Jewish State be accomplished without the gravest trespass upon the 'civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.' The fact came out repeatedly in the Commission's conference with Jewish representatives, that the Zionists looked forward to a practically complete dispossession of the present non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine, by various forms of purchase."

The British Mandate for Palestine (1923-1948)

- Following World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Britain came to control Palestine, with the newly created League of Nations endorsing British provisional rule over the area, known as the British Mandate for Palestine, in 1923. The mandate was supposed to be temporary ahead of full independence for the country.

- The 1920s witnessed increased conflict between Zionist Jews and Palestinian Arabs, as the number of Jewish immigrants from Europe grew, and as growing numbers of Palestinians were displaced by Jewish National Fund land purchases. Between 1922 and 1931, the Jewish population of Palestine more than doubled, from approximately 84,000 to approximately 175,000.During the same period, the Arab population of Palestine grew from approximately 560,000 to approximately 792,000.

- In 1920, 1921, and most seriously in 1929, bouts of violence erupted between Arabs and Jews, claiming hundreds of lives on both sides. In 1929, the unrest was also fueled by frustration with the British, who had failed to end their rule or grant independence.

- Following Adolph Hitler's rise to power in Germany in 1933, Jewish immigration to Palestine from Europe greatly increased, as Hitler's fascist Nazi regime instituted racist laws targeting Jews and other minorities and a European war grew imminent. Between 1931 and 1941, the Jewish population of Palestine more than doubled again, from approximately 175,000 to approximately 474,000. During the same period, the Arab population of Palestine grew from approximately 792,000 to approximately 1,045,000.

- Throughout the 1930s, tensions between Arabs, Jews, and the British continued to mount, culminating in the Arab Revolt of 1936.

- In 1936, a major rebellion against British rule and Zionist immigration broke out in Palestine. Initially, the Arab Revolt in Palestine consisted mainly of nonviolent actions such as labor strikes, boycotts, withholding payment of taxes, and protests. When this failed to cause the British to leave or halt the immigration of Jewish European colonists, a widespread armed uprising broke out in 1937.

- In April 1937, the Arab Higher Committee was formed by Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti (senior Sunni Muslim cleric) of Jerusalem, and a group of other notables. The Committee would act as the main political leadership of the Palestinian national movement until 1948.

- In October 1937, following attacks against Jews, the Zionist Irgun militia carried out a series of large bombings against Palestinian civilian targets across the country (see below for more on the Irgun). As Israeli historian Benny Morris observed in Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-1998, these attacks "[...introduced] a new dimension into the conflict... Now, for the first time, massive bombs were placed in crowded Arab centers, and dozens of people were indiscriminately murdered and maimed - for the first time more or less matching the numbers of Jews murdered in Arab pogroms and rioting of 1929 and 1936. This 'innovation' soon found Arab imitators and became something of a 'tradition': during the coming decades Palestine's (and, later, Israel's) marketplaces, bus stations, movie theaters, and other public buildings became routine targets, lending a particularly brutal flavor to the conflict."

- The British finally managed to suppress the Arab Revolt in 1939, with the help of Zionist militias. The same year, the British government of Neville Chamberlain issued a policy statement known as the White Paper of 1939. In the White Paper, Chamberlain's government retreated from an earlier recommendation, made in 1937's Peel Commission Report, [PDF] calling for the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, and instead endorsed the creation of an independent binational Palestinian state governed by Arabs and Jews in proportion to their size of the population. The White Paper also set limits on Jewish immigration into the country.

- In crushing the Arab Revolt in Palestine, the British severely weakened the Palestinian national movement by killing, jailing, and exiling Palestinian leaders (including members of the Arab Higher Committee), suppressing Palestinian political activity, and disarming Palestinian militias. These measures would have serious implications for the next major outburst of violence between Arabs and Jews a decade later. For while Palestinian political activity was stifled, the British allowed the Zionist movement to arm itself and "carve out an independent enclave for itself in Palestine as the infrastructure for a future state," in the words of Israeli historian Ilan Pappe (The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 15).

The Irgun & Lehi: Zionist Terrorism on the Rise (1937-1948)

- In 1931, a right-wing militia called the Irgun (also known as Etzel) was founded as an offshoot of the main Zionist militia in Palestine, the Haganah (the predecessor of the Israeli army). Irgun members were followers of the right-wing Zionist revisionist Zeev Jabotinsky and sought to create a Jewish state in all of historic Palestine as well as parts of neighboring Arab countries like Jordan, believing armed struggle was the only way to achieve this end. The Irgun's leaders included future Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who also founded the forerunner of today's Likud Party, the Herut, in 1948.

- Between 1937 and 1948, when it was integrated into the newly created Israeli army, the Irgun waged a campaign of violence and terror against Palestinians and the British. The Irgun, which was considered a terrorist organization by the British and American governments, carried out dozens of bombings and other attacks against Palestinian targets such as markets and other public places, killing hundreds of civilians. Although most of their operations were carried out in Palestine, Irgun members also attacked British targets abroad, bombing the British embassy in Rome in 1946 and a British military train in Austria in 1947.

- The Irgun's most high-profile attack was the bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in July 1946, which killed some 92 people, including 28 British citizens. The hotel was targeted because it was home to the British administrative and military headquarters in Palestine. (In 2006, current Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu attended a ceremony at the hotel for the unveiling of a plaque honoring the bombers, drawing the ire of the British government which sent a letter to the mayor of Jerusalem stating: "We don't think it's right for an act of terrorism to be commemorated.")

- In 1940, a splinter group of the Irgun, Lehi (also known as the Stern Gang), was founded by Avraham Stern. Lehi, which would subsequently be led by another future Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir, carried out numerous terrorist attacks against both British and Arab civilian targets. The most notorious Lehi attacks include the assassinations of Lord Moyne, the British Minister Resident in the Middle East in 1944, and Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat appointed United Nations Mediator in Palestine, in 1948. As an official with the Red Cross during World War II, Bernadotte had helped to save thousands of Jews and others from the Nazis late in the war.

- Together, members of the Irgun and Lehi carried out one of the most notorious atrocities in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the massacre of approximately 100 men, women, and children in the village of Deir Yassin, near Jerusalem, on April 16, 1948. The massacre at Deir Yassin, which is commemorated annually by Palestinians around the world, accelerated the flight of the Palestinian population and was a pivotal moment in the creation of Israel as a Jewish majority state. (See below for more on the massacre at Deir Yassin.)

- The outbreak of World War II in September 1939 was a major turning point for the conflict between Zionists and Palestinians. Once again, the Middle East became a battleground, this time between the Axis and Allied powers.

- Most Jewish organizations in Palestine, including militant groups, temporarily put aside their fight against the British, as the war against the anti-Semitic Nazi regime took precedence. For their part, the leadership of the Arab Higher Committee under Husseini sought the support of the Germans in their struggle against the British, as did other nationalist movements fighting British rule such as the Irish Republican Army and even some right-wing Zionists like the Lehi militia.

- Following the war and the revelation of the extent of the crimes carried out against Jews by the Nazis, the Zionist campaign for a Jewish state intensified and gained increasing international support, including in the United States, which would soon take over from the British as the dominant western power in the Middle East. For many in the west, the guilt of not doing enough to prevent the murder of millions of Jews in the Holocaust, and of shutting their borders to Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis before and during the war outweighed any considerations they may have had for the rights or wishes of the native inhabitants of Palestine, whose land would have to be taken for the creation of a Jewish state.

2. THE NAKBA: CREATING ISRAEL ON THE RUINS OF PALESTINE

|

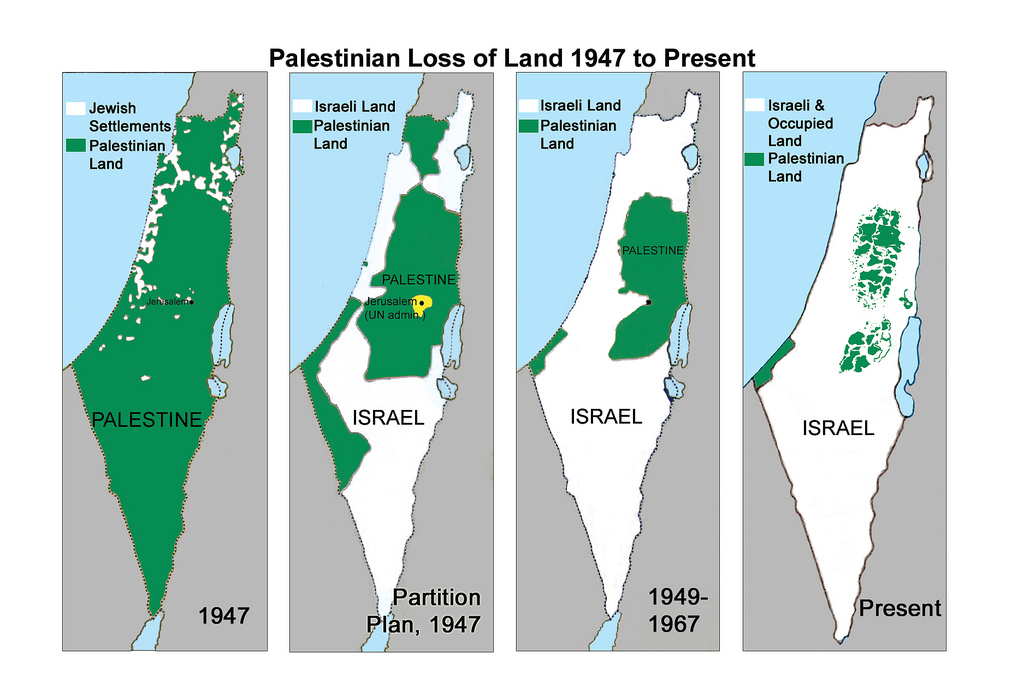

Maps of the distribution of Jewish settlements in 1947, the Arab and Jewish states called for under the 1947 Partition Plan, and subsequent Israeli expansionism

"We walked outside, Ben-Gurion accompanying us. [Yigal] Allon repeated his question, 'What is to be done with the Palestinian population?' Ben-Gurion waved his hand in a gesture which said 'Drive them out!'... I agreed that it was essential to drive the inhabitants out." - Former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin |

The United Nations Partition Plan (November 1947)

3. THE ONGOING NAKBA: 1948 TO PRESENT

"We must cleanse the country of Arabs and resettle them in the countries where they came from." - Rabbi Dov Lior, leading member of the religious Zionist movement, head of the settler Council of Rabbis of Judea and Samaria, and chief rabbi of the settlement of Kiryat Arba, 2008.

Palestinians Who Remained Inside Israel

The "Judaization" of East Jerusalem: Ethnic Cleansing by Bureaucracy

Stifling of Palestinian Movement & Economic Activity

Israel's West Bank Wall

65 Years of Apartheid in the Holy Land

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem: 1947-1949, by Benny Morris (1989)

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, by Benny Morris (2004)

Survival of the Fittest, Haaretz newspaper interview with Benny Morris (2004)

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, by Ilan Pappe (2006)

The Question of Palestine, by Edward Said (1992)

The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood, by Rashid Khalidi (2006)

All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, by Walid Khalidi (1992, 2006)

Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians 1876-1948, by Walid Khalidi (1984)

Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of Transfer in Zionist Political Thought; 1882-1948, by Nur Masalha (1992)

War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, edited by Avi Shlaim and Eugene L. Rogan (2007)

The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World, by Avi Shlaim (2000)

Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict, by Norman G. Finkelstein (2003)

The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities, by Simha Flapan (1988)

Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine, by Avi Shlaim (1988)

One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate, by Tom Segev (2001)

Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question, edited by Edward Said and Christopher Hitchens (1988)

The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel and the Palestinians, by Noam Chomsky (1983)

Palestinians in Israel: Segregation, Discrimination and Democracy, by Ben White (2011)

The Right to Return: The Case of the Palestinians, Amnesty International Policy Statement (2001)

Off the Map: Land and Housing Rights Violations in Israel's Unrecognized Bedouin Villages, Human Rights Watch (2008)

Separate and Unequal: Israel's Discriminatory Treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Human Rights Watch (2010)

- In February 1947, seeking to extricate itself from a steadily deteriorating situation on the ground, including the terrorist campaign being waged against British targets by the Irgun and Lehi, the British government announced that it would end its mandate and turn over responsibility for the future of Palestine to the newly-created United Nations.

- After intense lobbying by Zionist organizations and their supporters, on November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 181 calling for the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. The final vote was 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions and 1 absent. Those voting in favor included both emerging superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. The British abstained.

- The Partition Plan allocated approximately 55% of Mandatory Palestine to the Jewish state and just 42% to the Arab state, despite the fact that Jews made up only about one third of the population, many of whom were recent immigrants from Europe, and only owned about 7% of the privately owned land in Palestine. The city of Jerusalem was to be placed under international administration. (See here [PDF] for map: Zionist and Palestinian land ownership in percentages by subdistrict, 1945)

- The Arab Higher Committee rejected the Partition Plan outright, as well as the idea that Palestinians should give up more than half their country to newly arrived European immigrants who owned only a tiny amount of the land they were being given. For its part, the mainstream Zionist leadership under Ben-Gurion publicly welcomed the plan, as it constituted international legal recognition for a Jewish state in Palestine, while having no intention of being bound by its proposed borders. As Ben-Gurion put it, the borders of the new Jewish state, "will be determined by force and not by the partition resolution." (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 37)

- Almost immediately after the passing of the partition plan, renewed violence broke out between Arabs and Jews and the large-scale dispossession of Palestinians began. As December progressed, the Irgun and other Zionist militias intensified their attacks against Palestinian civilians and the British, killing and wounding hundreds.

- Within two weeks of the passing of the Partition Plan, more than 200 Arabs and Jews had been killed, and by the end of December almost 75,000 Palestinians had already been displaced by Zionist attacks. (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 40)

- In early January, members of the Arab Liberation Army (ALA), a ragtag group of volunteers from neighboring Arab countries formed by the Arab League, entered Palestine to help the outnumbered and outgunned Palestinian defenders. The Arab volunteers were themselves disorganized, poorly armed and trained, and failed to coordinate with local Palestinian fighters due to hostility between the Arab League and Arab Higher Committee. The British High Commissioner of Palestine at the time, Alan Cunningham, later described the ALA as "poorly equipped and badly led." Predicting an easy Zionist victory against the Arabs, Cunningham added: "In almost every engagement the Jews have proved their superiority in organisation, training and tactics."

- Surveying the situation, Ben-Gurion was also confident of an easy victory for Zionist forces as the country slid deeper into civil war. In February, in response to a letter from Moshe Sharett (who would become Israel's second prime minister) complaining that Zionist forces were sufficiently armed for self-defense but not to "take over the country," Ben-Gurion replied:

"If we will receive in time the arms we have already purchased, and maybe even receive some of that promised to us by the UN, we will be able not only to defend [ourselves] but also to inflict death blows on the Syrians in their own country - and take over Palestine as a whole. I am in no doubt of this. We can face all the Arab forces. This is not a mystical belief but a cold and rational calculation based on practical examination." (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 46) - The same month, February, the Haganah began mobilizing for full-scale war. According to the historian Pappe, by May 1948 the Zionists had some 50,000 fighters under arms versus no more than about 10,000 Palestinian irregulars and Arab volunteers.

- On March 10, 1948, the Zionist leadership under Ben-Gurion formally approved Plan Dalet (also known as Plan D), the blueprint for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. The operational military orders of Plan Dalet specified which Palestinian population centers should be targeted and laid out in detail a plan for their forcible depopulation [PDF] and destruction. It called for: "Mounting operations against enemy population centers located inside or near our defensive system in order to prevent them from being used as bases by an active armed force. These operations can be divided into the following categories:

"Destruction of villages (setting fire to, blowing up, and planting mines in the debris), especially those population centers which are difficult to control continuously.

"Mounting search and control operations according to the following guidelines: encirclement of the village and conducting a search inside it. In the event of resistance, the armed force must be destroyed and the population must be expelled outside the borders of the state."

- As Benny Morris observed in The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem: 1947-1949, Plan Dalet was "a strategic-ideological anchor and basis for expulsions by front, district, brigade and battalion commanders" providing "post facto, a formal, persuasive covering note to explain their actions."

- The Haganah began attacks under Plan Dalet at the beginning of April 1948. Expulsions now accelerated and became more systematic, marking a new phase in the conflict in which Zionist and then Israeli forces went on the offensive. According to Morris, "In the months of April-May 1948, units of the Haganah were given operational orders that stated explicitly that they were to uproot the villagers, expel them and destroy the villages themselves."

- On April 9, members of the Irgun and Stern Gang attacked the village of Deir Yassin outside of Jerusalem, massacring approximately 100 men, women, and children. News of the massacre spread quickly, fueling panic and the mass flight of Palestinians. (See below for more on the massacre at Deir Yassin and other atrocities carried out against Palestinian civilians.)

- In late April, all but 4,000 of the 70,000 Arab inhabitants of the city of Haifa were expelled. The operation officer of the Haganah forces that conquered Haifa, Mordechai Maklef - who would later become chief of staff of the Israeli army - ordered his troops to "Kill any Arab you encounter; torch all inflammable objects, and force doors open with explosives." (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 95) Crowds of Palestinians seeking safety in a marketplace near the port were deliberately shelled by Zionist forces, causing a panicked flight towards the waterfront as people rushed to evacuate by sea. Many drowned as overloaded boats sank attempting to shuttle people to safety. A witness recalled the terrible scene: "Men stepped on their friends and women on their own children. The boats in the port were soon filled with living cargo. The overcrowding in them was horrible. Many turned over and sank with all their passengers." (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 96)

- Many of the attacks carried out by Zionist forces during this period - prior to Israel's declaration of independence and subsequent war with Arab states - were in areas outside of the borders of the Jewish state proposed in the UN Partition Plan. (See here for map of such operations carried out between April 1 and May 15)

Plan Dalet

- (May 15, 1948 - March 1949)

- By early May 1948, more than 200 [PDF] Palestinian towns and villages had already been depopulated as people fled in fear or were forcibly expelled by Zionist forces, and between 250,000 and 350,000 Palestinians had been uprooted and made refugees.

- On May 14, Ben-Gurion and the Zionist leadership declared an independent state of Israel. The next day, the British, who had stood by and done nothing to stop the expulsions of Palestinians in the preceding months, withdrew the last of their soldiers as armies from Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Iraq launched a half-hearted and ill-fated attack against the newly declared state. None of the Arab governments wanted to intervene, but were compelled to do so by the force of public opinion in their countries, which sympathized with the Palestinians. In addition to being preoccupied with domestic concerns, the leaders of these countries, most of which had only recently acquired nominal independence from European colonial rule, were in fierce competition with one another and failed to coordinate their efforts in any serious way, frequently working at cross purposes.

- Crucially, since the end of World War II, the government of King Abdullah I of Jordan had been holding secret discussions with the Zionist leadership and had agreed to divide Palestine up between Jordan and the new Jewish state. Abdullah viewed the Palestinian national movement as a threat and wanted to expand the borders of his country to include parts of Palestine. In July 1946, a British diplomat sent a cable to the government about a recent meeting with Abdullah, reporting that he "is for partition and he feels that the other Arab leaders may acquiesce in that solution, although they may not approve of it openly." As part of the agreement Abdullah pledged not to allow Jordan's British-trained armed forces, the Arab Legion - by far the best Arab army at the time - to take part in joint operations with other Arab armies against Israel in the event of war, or to enter areas of Palestine designated for the Jewish state under the Partition Plan.

- The Iraqi government also ordered its armed forces not to enter areas that were supposed to be part of the Jewish state under the UN plan. For its part, the Syrian army barely advanced, maintaining a defensive posture for most of the war. The Lebanese, who had also declared war on Israel, didn't even send troops across the frontier. The Egyptian effort was also half-hearted and disorganized. As future Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who fought in the war, later wrote [PDF] in his memoirs:

"This could not be a serious war. There was no concentration of forces, no accumulation of ammunition or equipment. There was no reconnaissance, no intelligence, no plans. Yet we were actually on the battleï¬eld... The only conclusion that could be drawn was that this was a political war, or rather a state of war and no-war. There was to be advance without victory and retreat without defeat.",

- As predicted by Ben-Gurion, the combined Arab armies were no match for the new Israeli army. According to Israeli historian Ilan Pappe, by the end of the summer the new Israeli army had about 80,000 soldiers at its disposal, while the opposing Arab states didn't exceed 50,000 soldiers combined (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 45). Moreover, many Zionist and Israeli fighters were veterans of World War II, experienced with the weaponry and tactics of modern warfare, while most Arab soldiers were not.

- On May 24, just ten days after declaring independence, things were going so well for the Israelis militarily that Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary:

"We will establish a Christian state in Lebanon, the southern border of which will be the Litani River. We will break Transjordan [Jordan], bomb Amman and destroy its army, and then Syria falls, and if Egypt will still continue to fight - we will bombard Port Said, Alexandria and Cairo. This will be in revenge for what they (the Egyptians, the Aramis and Assyrians) did to our forefathers during Biblical times." (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 144)The same day, the Israelis received a shipment of weaponry from Eastern Europe, ensuring the supremacy of Israeli artillery for the rest of the war. (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 144) - In late May, the Israeli government set up an unofficial body, the "Transfer Committee," to oversee the destruction of Palestinian towns and villages or their repopulation with Jews, and to prevent displaced Palestinians from returning to their homes. In a report presented to Prime Minister Ben-Gurion in June 1948, the three-man committee, which included the Jewish National Fund's Joseph Weitz, called for the "destruction of villages as much as possible during military operations."

- From June to September, the expulsions continued. In July, Israeli forces expelled 70,000 Palestinians from the cities of Lydd and Ramla. In his memoirs, which were censored by the Israeli military but leaked to The New York Times in 1979, the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin recalled a conversation he had in July 1948 with Ben-Gurion, when Rabin was an officer in the Israeli army, regarding the fate of the Palestinians of Lydd and Ramla. Rabin wrote: "We walked outside, Ben-Gurion accompanying us. [Commander Yigal] Allon repeated his question, 'What is to be done with the Palestinian population?' Ben-Gurion waved his hand in a gesture which said 'Drive them out!'"Rabin added, "I agreed that it was essential to drive the inhabitants out."

- Expanding far beyond the proposed borders of the Jewish state delineated in the Partition Plan, which was allocated about 55% of Palestine, by the time Israeli forces stopped their advance they were in control of 78% of mandate Palestine. (See here for map of 1949 armistice lines) The remaining 22%, comprising the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza, fell under Jordanian and Egyptian control, respectively. Sixty-five years later, Israel has yet to officially declare its borders as it continues to colonize the West Bank and East Jerusalem, conquered during the June 1967 War.

- From 1947 to 1950, between 750,000 [PDF] and one million Palestinians were expelled by Zionist and then Israeli forces from the newly created Jewish state. It's estimated that about half of them fled under direct assault by Zionist forces.

Massacres & Atrocities Against Palestinian Civilians - During Israel's creation, Zionist paramilitaries and the Israeli army carried out numerous massacres and atrocities against Palestinian civilians, including rapes, [PDF] which were instrumental in spurring the mass flight of Palestinians that facilitated the establishment of a Jewish majority state. According to historian Benny Morris, there were two dozen such massacres.

- The most notorious atrocity committed during Israel's creation took place on April 9, 1948, in the village of Deir Yassin near Jerusalem (close to where Israel's Holocaust Memorial now stands), where approximately 100 men, women, and children were murdered by members of the Irgun and Lehi. Seventy-five of the victims were women, children, or elderly people. According to eyewitness accounts from survivors and reports from Zionist fighters, many of the victims were paraded in trucks through the streets of Jerusalem before being killed. One eyewitness, Fahim Zaydan, who was 12-years-old at the time and was shot and left for dead, recalled:

"They took us out one after the other; shot an old man and when one of his daughters cried, she was shot too. Then they called my brother Muhammad, and shot him in front [of] us, and when my mother yelled, bending over him - carrying my little sister Hudra in her hands, still breastfeeding her - they shot her too." (Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, p. 90) - Other notable atrocities against Palestinian civilians took place in the towns of Lydd (Lod), Dawayima, Saliha, Safsaf, and Tantura. Regarding the scope and nature of these massacres, in a 2004 interview with Haaretz newspaper, the historian Morris stated:

"In some cases four or five people were executed, in others the numbers were 70, 80, 100. There was also a great deal of arbitrary killing. Two old men are spotted walking in a field - they are shot. A woman is found in an abandoned village - she is shot. There are cases such as the village of Dawayima [in the Hebron region], in which a column entered the village with all guns blazing and killed anything that moved.

"The worst cases were Saliha (70-80 killed), Deir Yassin (100-110), Lod (250), Dawayima (hundreds) and perhaps Abu Shusha (70). There is no unequivocal proof of a large-scale massacre at Tantura, but war crimes were perpetrated there. At Jaffa there was a massacre about which nothing had been known until now. The same at Arab al Muwassi, in the north. About half of the acts of massacre were part of Operation Hiram [in the north, in October 1948]: at Safsaf, Saliha, Jish, Eilaboun, Arab al Muwasi, Deir al Asad, Majdal Krum, Sasa. In Operation Hiram there was a unusually high concentration of executions of people against a wall or next to a well in an orderly fashion."That can't be chance. It's a pattern. Apparently, various officers who took part in the operation understood that the expulsion order they received permitted them to do these deeds in order to encourage the population to take to the roads. The fact is that no one was punished for these acts of murder. Ben-Gurion silenced the matter. He covered up for the officers who did the massacres."

- From 1947 to 1950, between 750,000 [PDF] and one million Palestinians were ethnically cleansed during the creation of the state of Israel. It's estimated that about half of them fled under direct assault by Zionist forces.

- To ensure that the newly created state retained a Jewish majority, two laws were passed: the Law of Return (1950), which grants Jews from anywhere in the world the right to immigrate to Israel and become a citizen, and the Entry into Israel Law (1952) which was designed to prevent the return of Palestinian refugees.

- Today, the Palestinian refugee population is the largest and longest-standing population of displaced persons in the world. Reliable figures on their numbers are hard to find, however, a survey released in 2010 by BADIL, the Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, found the refugee and displaced population to be at least 7.1 million, made up of 6.6 million refugees and 427,000 internally displaced persons. It also found that refugees comprised 67% of the Palestinian population as a whole.

- Most Palestinian refugees are Palestinians and their descendants who were expelled from their homes in the parts of historic Palestine that were incorporated into the newly created state of Israel in 1948. Other Palestinian refugee categories include Palestinians who fled their homes but remained internally displaced in areas that became Israel in 1948; Palestinians who were displaced for the first time after Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza Strip in the 1967 War; Palestinians who left the occupied territories since 1967 and have been prevented by Israel from returning due to revocation of residency rights, denial of family reunification, or deportation; and Palestinians internally displaced in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip since 1967.

- Most Palestinian refugees live in camps in the occupied territories and neighboring Arab countries, with 1.9 million in Jordan, 1.1 million in Gaza, some 779,000 in the West Bank, 427,000 in Syria (prior to the ongoing civil war), and 425,000 in Lebanon. Most rely on the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), established in December 1949, to survive.

- Under international law, all refugees have a legal right to return to homes and property left behind during conflict, regardless of whether they left of their own volition or were forcibly expelled. Moreover, as noted by Human Rights Watch, the right of return "is a right that persists even when sovereignty over the territory is contested or has changed hands."

- In December 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194 regarding the situation in Palestine/Israel. It states: "refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible." The Palestinian right of return has been endorsed repeatedly by the UNGA, including through Resolution 3236 (1974), which "Reaffirms also the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and calls for their return."

- Israel's admittance as a member of the UN in May 1949 was conditioned on its acceptance of UN Resolution 194, which, 65 years later, it has yet to implement.

- The Palestinian right of return has been recognized by major human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. In 2001, Amnesty issued a policy statement [PDF] on the subject, which called "for Palestinians who fled or were expelled from Israel, the West Bank or Gaza Strip, along with those of their descendants who have maintained genuine links with the area, to be able to exercise their right to return."

- The U.S. government supported Resolution 194, and consistently voted to affirm it until 1993, when the administration of President Bill Clinton began to refer to Palestinian refugee rights as a matter to be negotiated between the two parties in a final peace agreement.

The Right of Return

See here for more on Palestinian refugees and the right of return

- Between 1948 and 1950, Zionist and Israeli forces ethnically cleansed more than 400 Palestinian towns and villages, including homes, businesses, houses of worship, and vibrant urban centers, which were systematically destroyed or repopulated with Jews. Most of them were demolished to prevent the return of their Palestinian owners, now refugees outside of Israel's pre-1967 borders, or internally displaced inside of them.

- During the 1948 War and immediately afterwards, Israel expropriated approximately 4,244,776 [PDF] acres of land belonging to Palestinians who were made refugees during the creation of the state.

- In 1950, Israel passed the "Absentees' Property Law," which granted the government "custodianship" over lands and property belonging to Palestinian refugees, with no compensation for the owners. An "absentee" was defined as any Palestinian who left his or her home after November 1947, even if he or she remained within what became Israel's borders.

- The total monetary loss of Palestinians dispossessed during Israel's creation has been estimated at between of $100 billion and $200 billion [PDF] (US) in today's dollars.

- As Zionist and Israeli forces swept across the country, expelling Palestinians as they went, tens of thousands of Palestinian books were systematically "collected" by the Haganah and the Israeli army, in cooperation with the Israeli National Library. The books included priceless volumes of Palestinian Arab and Muslim literature, including poetry, works of history and fiction. Thousands of the books were destroyed and recycled for paper, while others were added to the library's collection. Today, many remain in the Israeli National Library, designated abandoned property.

(See here for interactive map of Palestinian population centers destroyed during Israel's creation)

3. THE ONGOING NAKBA: 1948 TO PRESENT

"We must cleanse the country of Arabs and resettle them in the countries where they came from." - Rabbi Dov Lior, leading member of the religious Zionist movement, head of the settler Council of Rabbis of Judea and Samaria, and chief rabbi of the settlement of Kiryat Arba, 2008.

Palestinians Who Remained Inside Israel

- Following the 1948 War, approximately 150,000 Palestinians remained inside what became Israel's borders, many of them internally displaced. They were granted Israeli citizenship but stripped of most of their land and placed under martial law, which they were subject to until 1966.

- Between 1948 and 1967, Israel expropriated approximately 172,973 [PDF] acres of land belonging to Palestinian citizens of the state.

- In 1949, there were approximately 30,000-40,000 Palestinians internally displaced within Israel, prevented from returning to their homes, which were destroyed or taken over by Jews. Today Israel continues to refuse to recognize the rights of internally displaced Palestinians, whose number is estimated at approximately 300,000.[PDF]

- Today there are approximately 1.6 [PDF] million Palestinian citizens of Israel (sometimes referred to as "Israeli Arabs"), making up about 20% of the population. They face widespread, systematic discrimination in virtually all aspects of life, dealing with everything from employment and housing to land ownership and family reunification rights.

- The 2012 US State Department Country Report on Human Rights Practices for Israel and the Occupied Territories, [PDF] released in April 2013, noted that Palestinian citizens of Israel suffer from "institutional and societal discrimination in particular in access to equal education and employment opportunities."

- There are more than 50 Israeli laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens of Israel.

- 93% of the land in Israel is state controlled by the Israel Land Authority and quasi-governmental Jewish National Fund, which discriminate against non-Jewish citizens.

- Tens of thousands [PDF] of Bedouin and other non-Jewish citizens of Israel live in villages that aren't recognized by the state or provided basic services like water or electricity. At least 30,000 Bedouin citizens of Israel currently face eviction from their ancestral lands in the Negev desert, part of an Israeli government plan to "Judaize" the area.

- Sixty-five years after the mass expulsions of the Nakba, Israeli political and religious leaders continue to call for Palestinian citizens of the state to be transferred, "voluntarily" or by force, to a separate Palestinian state or outside historic Palestine altogether. According to the Jerusalem Post, a 2008 Israeli government poll showed that "A total of 76 percent of Israeli Jews give some degree of support to transferring Israeli Arabs to a future Palestinian state."

- In June 1967, Palestinians suffered another major blow when Israel conquered the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, along with the Syrian Golan Heights, and Egyptian Sinai Peninsula (the latter of which was returned to Egypt as part of the Camp David peace agreement). (See here for more on the 1967 War.) In doing so, Israel came to control the 22% of historic Palestine that remained outside its expanded borders in 1948.

- During the war, approximately 300,000 [PDF] Palestinians were displaced from the West Bank and Gaza, approximately 175,000 [PDF] of whom became refugees for the second time.

- Immediately after the 1967 War, Israel expropriated approximately 209,792 [PDF] acres of Palestinian land in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza.

- Since 1967, Israel has ruled by military decree over millions of Palestinians in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, granting them no political or civil rights while relentlessly colonizing their land [PDF] with Jewish-only settlements in violation of international law. (For more on the occupation and settlements see our fact sheet 45 Years of Occupation, released in June 2012)

- Today there are more than a half million Jewish settlers living in about 130 official Jewish settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem and about 100 settler "outposts" (nascent settlements built without official approval, but often with support and assistance from government ministries). (See here for Peace Now's interactive "Facts on the Ground" settlement map)

- Settlements and attendant infrastructure like Israeli-only roads cover approximately 42% of the area of the occupied West Bank - much of it privately-owned Palestinian land - dividing and isolating Palestinian population centers into separate, easily controlled bantustans surrounded by walls and military checkpoints.

- Since 1967, Israel has demolished approximately 27,000 Palestinian homes in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza. Most demolitions are carried out for three stated reasons: military purposes; "administrative" reasons (i.e. a home or structure is built without difficult to obtain permission from Israel); or with the intent of deterring or punishing militants and their families, a violation of provisions of international law that bar collective punishment. (See here for more on Israel's demolition of Palestinian homes.)

The "Judaization" of East Jerusalem: Ethnic Cleansing by Bureaucracy

- According to Israeli human rights organization B'Tselem: "Since East Jerusalem was annexed in 1967, the government of Israel's primary goal in Jerusalem has been to create a demographic and geographic situation that will thwart any future attempt to challenge Israeli sovereignty over the city. To achieve this goal, the government has been taking actions to increase the number of Jews, and reduce the number of Palestinians, living in the city."

- According to the 2009 US State Department International Religious Freedom Report:

"Many of the national and municipal policies in Jerusalem were designed to limit or diminish the non-Jewish population of Jerusalem. According to Palestinian and Israeli human rights organizations, the Israeli Government used a combination of zoning restrictions on building by Palestinians, confiscation of Palestinian lands, and demolition of Palestinian homes to 'contain' non-Jewish neighborhoods while simultaneously permitting Jewish settlement in predominantly Palestinian areas in East Jerusalem." - 35% of land in East Jerusalem has been confiscated for Israeli settlement use, with only 13% zoned for Palestinian construction, much of which is already built-up.

- Methods used by Israel as part of an effort to "Judaize" or alter the religious composition of Jerusalem by increasing the number of Jews while decreasing the number of Palestinians, include:

- Revoking residency rights and social benefits of Palestinians who stay abroad for at least seven years, or who are unable to prove that their "center of life" is in Jerusalem. Since 1967, Israel has revoked the residency rights of about 14,000 East Jerusalem Palestinians, of which more than 4,500 were revoked in 2008.

- Encouraging Jewish settlement in historically Palestinian-Arab areas while severely restricting the expansion of Palestinian residential areas. The Israeli government, through official and unofficial organizations like the Israel Land Fund, encourages Jews to move to settlements in occupied East Jerusalem and take over houses in historically Arab neighborhoods like Silwan and Sheikh Jarrah, sometimes evicting their Palestinian inhabitants in the process. Several hundred Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem are currently at risk of forced displacement by settlers.

- Systematically discriminating against Palestinian residents of the city in municipal planning and the allocation of services and building permits. According to a 2011 report by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs:"Since 1967, Israel has failed to provide Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem with the necessary planning framework to meet their basic housing and infrastructure needs. Only 13 percent of the annexed municipal area is currently zoned by the Israeli authorities for Palestinian construction, much of which is already built-up. It is only within this area that Palestinians can apply for building permits, but the number of permits granted per year to Palestinians does not begin to meet the existing demand for housing and the requirements related to formal land registration prevent many from applying. As a result, Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem find themselves confronting a serious shortage in housing and other basic infrastructure. Many residents have been left with no choice other than to build structures 'illegally' and therefore risk demolition and displacement."

- Demolitions of Palestinian homes and structures built without difficult to obtain permission from Israeli authorities. Since 1967, approximately 2000 Palestinian homes have been demolished in East Jerusalem by Israel. The number of outstanding demolition orders is estimated to be as high as 20,000.

Stifling of Palestinian Movement & Economic Activity

- At any given time, there are upwards of 500 Israeli checkpoints, roadblocks, and other barriers to movement within the occupied West Bank - an area smaller than Delaware - hindering Palestinians and their goods from moving between their own towns and cities and the outside world. (See here [PDF] for December 2012 United Nations map: West Bank Access Restrictions)

- Since the early 1990s, Israel has restricted passage to and from Gaza, but in 2006, following Hamas' victory in Palestinian elections, Israel steadily tightened its restrictions and imposed a naval blockade on the tiny coastal enclave which continues to be in effect. (See here [PDF] for December 2012 United Nations map: Gaza Strip: Access and Closure)

- Palestinians living in the occupied West Bank and Gaza need difficult to obtain permission from Israel to visit occupied East Jerusalem. As a result, millions of Palestinians are not able to visit the city, historically the center of Palestinian economic and cultural life in the West Bank, or pray at its holy sites.

- Almost 80% of the Jordan Valley, which contains some of the best agricultural land in the occupied West Bank, is off-limits to Palestinians, designated for Jewish settlements, military "firing zones," and "nature reserves." (See here [PDF] for 2012 United Nations map of the Jordan Valley)

Israel's West Bank Wall

- In June 2002, under the pretext of security, the Israeli government began unilaterally constructing a wall, much of it on Palestinian land deep inside the occupied West Bank. (Since 1994, the Gaza Strip has been surrounded by walls on three sides, which cut off the 1.6 million Palestinians living there from the rest of the world.)

- As of May 2012, more than 325 miles of the wall had already been built, at a cost of $2.6 billion (US). Eighty-five percent of the wall will be built not along Israel's pre-1967 border, but on Palestinian land inside the occupied West Bank.

- Once completed, the full length of the wall will be between 420 and 440 miles (according to the Israeli Ministry of Defense and B'Tselem, respectively), more than twice the length of Israel's pre-1967 border with the West Bank.

- When finished, the wall, along with the settlements, Israeli-only highways and closed military zones, are projected to cover 46% of the West Bank, effectively annexing it to Israel.

- Critics have accused Israeli authorities of designing the wall's route to envelop as much Palestinian land and as many Israeli settlements as possible on the western, or Israeli side, while placing as many Palestinians as possible on the eastern side. Once complete, about 85% [PDF] of the Israeli settler population is expected to be on the Israeli side of the wall.

- The wall also surrounds much of occupied East Jerusalem, cutting its approximately 200,000 Palestinian residents off from the rest of the occupied West Bank.

- In July 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion [PDF] deeming the West Bank separation wall illegal. The court said the wall must be dismantled, and ordered Israel to compensate Palestinians harmed by its construction. It also called on third-party states to ensure Israel's compliance with the judgment.

- During construction of the wall, Israel has destroyed large amounts of Palestinian agricultural land and usurped water supplies, including the biggest aquifer in the West Bank.

65 Years of Apartheid in the Holy Land

- Over the entirety of its 65-year existence, there has been a period of only about one year (1966-67) that Israel has not ruled over large numbers of Palestinians to whom it granted no political rights simply because they are not Jewish. From 1948 to 1966, Palestinian citizens of Israel were ruled by martial law, similar to the Israeli military regime that millions of Palestinians living in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza have been subject to since 1967.

- The United Nations International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (1973) defines apartheid as "inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them."

- According to a 2010 Human Rights Watch report, "Separate and Unequal: Israel's Discriminatory Treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories":

"Palestinians face systematic discrimination merely because of their race, ethnicity, and national origin, depriving them of electricity, water, schools, and access to roads, while nearby Jewish settlers enjoy all of these state-provided benefits While Israeli settlements flourish, Palestinians under Israeli control live in a time warp - not just separate, not just unequal, but sometimes even pushed off their lands and out of their homes." - Many Israelis, including senior political leaders, have compared Israel's military rule over Palestinians in the occupied territories to apartheid. One of the first people to use the word "apartheid" in relation to Israel was Israel's first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who warned following the 1967 War of Israel becoming an "apartheid state" if it retained control of the occupied territories.

- In 1999, then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak stated: "Every attempt to keep hold of this area [Israel and the occupied territories] as one political entity leads, necessarily, to either a nondemocratic or a non-Jewish state. Because if the Palestinians vote, then it is a binational state, and if they don't vote it is an apartheid state." In 2010, Barak repeated the apartheid comparison, stating: "As long as in this territory west of the Jordan river there is only one political entity called Israel it is going to be either non-Jewish, or non-democratic If this bloc of millions of Palestinians cannot vote, that will be an apartheid state."

- Others who have compared Israel's treatment of Palestinians to apartheid include former US President Jimmy Carter, who in 2006 published a book entitled, "Palestine Peace Not Apartheid," as well as many veterans of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, such as Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, one of the heroes of the struggle against South African apartheid, who has repeatedly made the comparison.

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem: 1947-1949, by Benny Morris (1989)

The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, by Benny Morris (2004)

Survival of the Fittest, Haaretz newspaper interview with Benny Morris (2004)

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, by Ilan Pappe (2006)

The Question of Palestine, by Edward Said (1992)

The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood, by Rashid Khalidi (2006)

All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, by Walid Khalidi (1992, 2006)

Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians 1876-1948, by Walid Khalidi (1984)

Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of Transfer in Zionist Political Thought; 1882-1948, by Nur Masalha (1992)

War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, edited by Avi Shlaim and Eugene L. Rogan (2007)

The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World, by Avi Shlaim (2000)

Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict, by Norman G. Finkelstein (2003)

The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities, by Simha Flapan (1988)

Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine, by Avi Shlaim (1988)

One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate, by Tom Segev (2001)

Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question, edited by Edward Said and Christopher Hitchens (1988)

The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel and the Palestinians, by Noam Chomsky (1983)

Palestinians in Israel: Segregation, Discrimination and Democracy, by Ben White (2011)

The Right to Return: The Case of the Palestinians, Amnesty International Policy Statement (2001)

Off the Map: Land and Housing Rights Violations in Israel's Unrecognized Bedouin Villages, Human Rights Watch (2008)

Separate and Unequal: Israel's Discriminatory Treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Human Rights Watch (2010)

Israel Suppresses Al-Awda March, Assaults Journalists and Protesters

Israeli occupation forces suppressed Al-Awda (return) march near al-Khader village, south of Bethlehem. PNN reporter said that Israeli forces assaulted a number of journalists who were covering the march. Protesters closed Street 60 and the Israeli forces assaulted some of the protesters, fired sound and tear gas canisters in return.

Israeli forces arrested Mazen al-Azzeh, the coordinator of the popular committee to resist wall and settlement, after they handcuffed him and took him to an unknown location. Confrontations also erupted between the forces and young Palestinians inside al-Khader village.

It's worth noting that the march launched from the The Martyrs' Memorial, with the participation of hundreds of Palestinians and internationals activists from Bethlehem, and was supposed to continue its heading to Hussan village, west of Bethlehem toward the barrier that separates the lands of 1948 from the lands of 1967.

Our reporter said that the Israeli army suppressed the march near al-Khader stadium and started firing tear and sound gas bombs and banned participants from continuing their march.

Soldiers Suppress Demonstration Marking Nakba Day near Bethlehem

Israeli forces Tuesday suppressed a peaceful demonstration in the town of al-Khader, south of Bethlehem, marking “Nakba,” catastrophe, of 1948 when Palestinians were forced out of their homes in historic Palestine that led to the creation of Israel, according to a local activist.

Several cases of suffocation and fainting among the protesters were reported. Coordinator of the Popular Committee against Settlements and the Apartheid Wall in al-Khader, Ahmad Salah, told WAFA Israeli forces fired heavy amounts of tear gas and acoustic bombs toward the protesters, causing several suffocation and fainting cases among them that led to confrontations.

IOF soldiers quell “March of Return”

Israeli occupation forces (IOF) quelled on Tuesday morning the “March of Return” organized by Palestinian refugees to commemorate the 65th anniversary of Nakba.

Organizers said that the soldiers fired teargas at the participants, who marched from Doheisha refugee camp in Bethlehem to Khader village in an attempt to reach one of the villages of 1948 occupied Palestine west of Bethlehem, the inhabitants of which were forced to leave their homes back in 1948.

They said that a number of young men were treated for breathing difficulty while others managed to reach a bypass road nearby and threw stones at IOF vehicles and settlers’ cars.

Meanwhile, Jewish settlers hoisted Israeli flags and offered Talmudic rituals in Khader village.

Israeli forces arrested Mazen al-Azzeh, the coordinator of the popular committee to resist wall and settlement, after they handcuffed him and took him to an unknown location. Confrontations also erupted between the forces and young Palestinians inside al-Khader village.

It's worth noting that the march launched from the The Martyrs' Memorial, with the participation of hundreds of Palestinians and internationals activists from Bethlehem, and was supposed to continue its heading to Hussan village, west of Bethlehem toward the barrier that separates the lands of 1948 from the lands of 1967.

Our reporter said that the Israeli army suppressed the march near al-Khader stadium and started firing tear and sound gas bombs and banned participants from continuing their march.

Soldiers Suppress Demonstration Marking Nakba Day near Bethlehem

Israeli forces Tuesday suppressed a peaceful demonstration in the town of al-Khader, south of Bethlehem, marking “Nakba,” catastrophe, of 1948 when Palestinians were forced out of their homes in historic Palestine that led to the creation of Israel, according to a local activist.

Several cases of suffocation and fainting among the protesters were reported. Coordinator of the Popular Committee against Settlements and the Apartheid Wall in al-Khader, Ahmad Salah, told WAFA Israeli forces fired heavy amounts of tear gas and acoustic bombs toward the protesters, causing several suffocation and fainting cases among them that led to confrontations.

IOF soldiers quell “March of Return”

Israeli occupation forces (IOF) quelled on Tuesday morning the “March of Return” organized by Palestinian refugees to commemorate the 65th anniversary of Nakba.

Organizers said that the soldiers fired teargas at the participants, who marched from Doheisha refugee camp in Bethlehem to Khader village in an attempt to reach one of the villages of 1948 occupied Palestine west of Bethlehem, the inhabitants of which were forced to leave their homes back in 1948.

They said that a number of young men were treated for breathing difficulty while others managed to reach a bypass road nearby and threw stones at IOF vehicles and settlers’ cars.

Meanwhile, Jewish settlers hoisted Israeli flags and offered Talmudic rituals in Khader village.

|

|

‘Conference for refugees held in Gaza’

A conference for Palestine refugees has been held in Gaza to mark the 65th anniversary of the historic Nakba Day, Press TV reports. Leaders of Palestinian factions and representatives from Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and Egypt attended the conference, entitled “United for Return.” Following the establishment of the Israeli regime in 1948, some 700,000 Palestinians were expelled from their homeland because of the threat of being massacred. Palestinians commemorated the dispossession as Nakba. Hamas Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh said Palestinian refugees around the world “assert their adherence to the right of return” on Nakba Day. “The children and the grandchildren of the refugees will never give up the land of |

their ancestors, we will never give up an inch of Palestine not even a grain of sand from the land of Palestine,” he added.

The conference highlighted the right of return for thousands of Palestinian refugees who live in the Middle East and around the world.

It also emphasized the rejection of the Israeli regime’s resettlement or compensation as a substitute for the Palestinian refugee’s right of return.

Maram al-Madhoun, the conference spokeswoman, said the conference was organized to send a message to the world that the Palestinians have the right for return to their own villages and towns.

Organizers also said that the conference aimed to form a coalition of media and law organizations which are interested in refugees affairs and Palestinians right of return to their homeland.

The conference highlighted the right of return for thousands of Palestinian refugees who live in the Middle East and around the world.

It also emphasized the rejection of the Israeli regime’s resettlement or compensation as a substitute for the Palestinian refugee’s right of return.

Maram al-Madhoun, the conference spokeswoman, said the conference was organized to send a message to the world that the Palestinians have the right for return to their own villages and towns.

Organizers also said that the conference aimed to form a coalition of media and law organizations which are interested in refugees affairs and Palestinians right of return to their homeland.

Barghouthi: “Right Of Return, A Sacred Right”

In a statement released from his prison cell, detained Palestinian political leader, Marwan Barghouthi, stated that May 15, marks the 65th anniversary of the Nakba, when Israel was established in the historic land of Palestine, over the ruins of hundreds of displaced and destroyed villages and towns, and added that on this day, the Palestinians reaffirm their legitimate inalienable Right of Return to their homeland.

The Fateh leader said that the Palestinian people will never abandon their legitimate rights, and insist on the implementation of all related international resolutions, including United Nations General Assembly Resolution #194 regarding the Right of Return of the Palestinian refugees to their homeland.

He said that the Palestinians will continue to struggle for their rights, and added that the Palestinian struggle is noble fight to justice and liberation.

Barghouthi said that the Nakba is one of the ugliest crimes in human recent history, as the Palestinians faced horrific acts of ethnic cleansing, massacres and crimes, and added that Israel uprooted and displaced an entire nation, destroyed and burnt hundreds of villages, churches and mosques to replace them with Israeli cities.

He called on the Palestinian people to unite, and to intensify their legitimate struggle against the Israeli occupation and its settlements, and called for more activities in support of the Palestinian refugees, especially in Syria.

Barghouthi also called on the Palestinians and their factions to end the internal rifts and divisions, to form a unified leadership for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), a unified authority, and to form a national unity government that oversees new legislative and presidential elections in Palestine.

He called for more international campaigns, to achieve a full member status at the United Nations, and to conduct a unified strong boycott campaign to isolate Israel on all legal, political, cultural, and economic levels, and to ensure sanctions are imposed on Israel until it ends its illegal occupation and its illegitimate settlements.

In his statement, the detained leader said that the Palestinians must reject all attempts that aim at forcing them to abandon their legitimate rights, to insist on a full and comprehensive Israeli withdrawal from all of the Palestinian territories Israel occupied in 1967, including Jerusalem, to ensure the full implementation of resolution 194, and the liberation of all detainees.

As for direct negotiations with Israel, Barghouthi said that Israel must first acknowledge the legitimate Palestinian rights before talks are resumed, and added that any talk of modifications on the 1967 borders must be rejected.

“The Palestinians must not provide free concessions to the illegal occupation”, Barghouthi stated, “Our people will remain steadfast, and will continue to struggle for liberation, freedom and independence”.

The Fateh leader said that the Palestinian people will never abandon their legitimate rights, and insist on the implementation of all related international resolutions, including United Nations General Assembly Resolution #194 regarding the Right of Return of the Palestinian refugees to their homeland.

He said that the Palestinians will continue to struggle for their rights, and added that the Palestinian struggle is noble fight to justice and liberation.

Barghouthi said that the Nakba is one of the ugliest crimes in human recent history, as the Palestinians faced horrific acts of ethnic cleansing, massacres and crimes, and added that Israel uprooted and displaced an entire nation, destroyed and burnt hundreds of villages, churches and mosques to replace them with Israeli cities.

He called on the Palestinian people to unite, and to intensify their legitimate struggle against the Israeli occupation and its settlements, and called for more activities in support of the Palestinian refugees, especially in Syria.

Barghouthi also called on the Palestinians and their factions to end the internal rifts and divisions, to form a unified leadership for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), a unified authority, and to form a national unity government that oversees new legislative and presidential elections in Palestine.

He called for more international campaigns, to achieve a full member status at the United Nations, and to conduct a unified strong boycott campaign to isolate Israel on all legal, political, cultural, and economic levels, and to ensure sanctions are imposed on Israel until it ends its illegal occupation and its illegitimate settlements.

In his statement, the detained leader said that the Palestinians must reject all attempts that aim at forcing them to abandon their legitimate rights, to insist on a full and comprehensive Israeli withdrawal from all of the Palestinian territories Israel occupied in 1967, including Jerusalem, to ensure the full implementation of resolution 194, and the liberation of all detainees.

As for direct negotiations with Israel, Barghouthi said that Israel must first acknowledge the legitimate Palestinian rights before talks are resumed, and added that any talk of modifications on the 1967 borders must be rejected.

“The Palestinians must not provide free concessions to the illegal occupation”, Barghouthi stated, “Our people will remain steadfast, and will continue to struggle for liberation, freedom and independence”.

Palestinians mark 65th anniversary of Nakba Day