26 mar 2009

|

|

23 mar 2009

Guardian investigation uncovers evidence of alleged Israeli war crimes in Gaza

Palestinians claim children were used as human shields and hospitals targeted during 23-day conflict

Clancy Chassay investigates claims from three brothers that the Israeli military used them as human shields during the invasion of Gaza

Clancy Chassay investigates claims from three brothers that the Israeli military used them as human shields during the invasion of Gaza

|

|

Gaza war crimes investigation: human shields

The Guardian has compiled detailed evidence of alleged war crimes committed by Israel during the 23-day offensive in the Gaza Strip earlier this year, involving the use of Palestinian children as human shields and the targeting of medics and hospitals. A month-long investigation also obtained evidence of civilians being hit by fire from unmanned drone aircraft said to be so accurate that their operators can tell the colour of the clothes worn by a target. The testimonies form the basis of three Guardian films which add weight to calls this week for a full inquiry into the events surrounding Operation Cast Lead, which was aimed at Hamas but left about 1,400 Palestinians dead, including more than 300 children. The Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) refused to respond directly to the allegations made against its troops, but issued statements denying the charges and insisted international law had been observed. |

The latest disclosures follow soldiers' evidence published in the Israeli press about the killing of Palestinian civilians and complaints by soldiers involved in the military operation that the rules of engagement were too lax.

Amnesty International has said Hamas should be investigated for executing at least two dozen Palestinian men in an apparent bout of score-settling with rivals and alleged collaborators while Operation Cast Lead was under way.

Human rights groups say the vast majority of offences were committed by Israel, and that the Gaza offensive was a disproportionate response to Hamas rocket attacks. Since 2002, there have been 21 Israeli deaths by Hamas rockets fired from Gaza, and during Operation Cast Lead there were three Israeli civilian deaths, six Israeli soldiers killed by Palestinian fire and four killed by friendly fire.

"Only an investigation mandated by the UN security council can ensure Israel's co-operation, and it's the only body that can secure some kind of prosecution," said Amnesty's Donatella Rovera, who spent two weeks in Gaza investigating war crime allegations. "Without a proper investigation there is no deterrent. The message remains the same: 'It's OK to do these things, there won't be any real consequences'."

Some of the most dramatic testimony gathered by the Guardian came from three teenage brothers in the al-Attar family. They describe how they were taken from home at gunpoint, made to kneel in front of Israeli tanks to deter Hamas fighters from firing, and sent by Israeli soldiers into Palestinian houses to clear them. "They would make us go first so if any fighters shot at them the bullets would hit us, not them," 14-year-old Al'a al-Attar said.

Medics and ambulance drivers said they were targeted when they tried to tend to the wounded; sixteen were killed. According to the World Health Organisation, more than half of Gaza's 27 hospitals and 44 clinics were damaged by Israeli bombs.

Amnesty International has said Hamas should be investigated for executing at least two dozen Palestinian men in an apparent bout of score-settling with rivals and alleged collaborators while Operation Cast Lead was under way.

Human rights groups say the vast majority of offences were committed by Israel, and that the Gaza offensive was a disproportionate response to Hamas rocket attacks. Since 2002, there have been 21 Israeli deaths by Hamas rockets fired from Gaza, and during Operation Cast Lead there were three Israeli civilian deaths, six Israeli soldiers killed by Palestinian fire and four killed by friendly fire.

"Only an investigation mandated by the UN security council can ensure Israel's co-operation, and it's the only body that can secure some kind of prosecution," said Amnesty's Donatella Rovera, who spent two weeks in Gaza investigating war crime allegations. "Without a proper investigation there is no deterrent. The message remains the same: 'It's OK to do these things, there won't be any real consequences'."

Some of the most dramatic testimony gathered by the Guardian came from three teenage brothers in the al-Attar family. They describe how they were taken from home at gunpoint, made to kneel in front of Israeli tanks to deter Hamas fighters from firing, and sent by Israeli soldiers into Palestinian houses to clear them. "They would make us go first so if any fighters shot at them the bullets would hit us, not them," 14-year-old Al'a al-Attar said.

Medics and ambulance drivers said they were targeted when they tried to tend to the wounded; sixteen were killed. According to the World Health Organisation, more than half of Gaza's 27 hospitals and 44 clinics were damaged by Israeli bombs.

|

|

Gaza war crimes investigation: attacks on medics

In a report released today, a medical human rights group said there was "certainty" that Israel violated international humanitarian law during the war, with attacks on medics, damage to medical buildings, indiscriminate attacks on civilians and delays in medical treatment for the injured."We have noticed a stark decline in IDF morals concerning the Palestinian population of Gaza, which in reality amounts to a contempt for Palestinian lives," said Dani Filc, chairman of Physicians for Human Rights Israel. The Guardian gathered testimony on missile attacks by Israeli drones against clearly distinguishable civilian targets. In one case a family of six was killed when a missile hit the courtyard of their house. Israel has not admitted using drones but experts say their optical equipment is good enough to identify individual items of clothing worn by targets. The Geneva convention makes it clear medical staff and hospitals are not legitimate targets and forbids involuntary human shields. |

|

|

Gaza war crimes investigation: Israeli drones

The army responded to the claims. "The IDF operated in accordance with rules of war and did the utmost to minimise harm to civilians uninvolved in combat. The IDF's use of weapons conforms to international law," it said. The IDF said an investigation was under way into allegations hospitals were targeted. It said Israeli soldiers were under orders to avoid harming medics, but: "However, in light of the difficult reality of warfare in the Gaza Strip carried out in urban and densely populated areas, medics who operate in the area take the risk upon themselves." Use of human shields was outlawed by Israel's supreme court in 2005 after a string of incidents. The IDF said only Hamas used human shields by launching attacks from civilian areas. An Israeli embassy spokesman said any claims were suspect because of Hamas pressure on witnesses. |

"Anyone who understands the realities of Gaza will know these people are not free to speak the truth. Those that wish to speak out cannot for fear of beatings, torture or execution at the hands of Hamas," the spokesman said in a written statement.

However, the accounts gathered by the Guardian are supported by the findings of human rights organisations and soldiers' testimony published in the Israeli press.

An IDF squad leader is quoted in the daily newspaper Ha'aretz as saying his soldiers interpreted the rules to mean "we should kill everyone there [in the centre of Gaza]. Everyone there is a terrorist."

• This article was updated on Tuesday March 24 2009 to reflect changes made for the first edition of the Guardian newspaper.

However, the accounts gathered by the Guardian are supported by the findings of human rights organisations and soldiers' testimony published in the Israeli press.

An IDF squad leader is quoted in the daily newspaper Ha'aretz as saying his soldiers interpreted the rules to mean "we should kill everyone there [in the centre of Gaza]. Everyone there is a terrorist."

• This article was updated on Tuesday March 24 2009 to reflect changes made for the first edition of the Guardian newspaper.

20 mar 2009

IDF Testimony of Possible War Crimes

Death to arabs on the wall

by Richard Silverstein

Haaretz continues today with its coverage (in Hebrew) of testimony by IDF soldiers regarding their treatment of Gaza civilians during the recent war. Based on the information recounted it seems clear that a serious, in depth investigation of potential war crimes perpetrated by Israeli forces on orders from their superiors is necessary. The Israeli human rights group Yesh Din and Amnesty International have each called for such an inquiry.

Amnesty also brings word that 17 of the world’s most eminent jurists, many of whom conducted international war crimes tribunals (including Richard Goldstone), along with human rights activists (including Mary Robinson and Desmond Tutu) have called for a UN investigation of potential war crimes.

Their letter to Secretary General Ban Ki Moon can be read at the Amnesty site.

Amos Harel, the Haaretz reporter who first broke this story reports today that the IDF has launched a half-hearted investigation of the charges. But while going through the paces, it has also launched a frontal attack on Danny Zamir, the director of the Oranim College military preparatory program, who sponsored the meeting at which the soldiers revealed their stories.

Clearly, this is an IDF attempting to get out of dealing with the issues rather than addressing them forcefully. In the IDF, there is no such thing as bad behavior when it comes to mistreating Palestinians. The only time such activities are investigated and punished is when they’ve been videotaped for the world to see and the army cannot dispute what happened.

In this case, there is no documentary footage though there is the strong eyewitness testimony of soldiers on the ground. It remains to be seen whether this is of sufficient weight to rouse the military behemoth into action.

What follows is my translation of portions of the latest Haaretz story. Pay attention especially to the discussion of the religious zealotry of the Orthodox soldiers and how the rabbinate has turned the battle against the Palestinians into a holy war:

On Friday, Feburary , [Danny] Zamir brought together soldiers and captains, graduates of the military preparatory program, for a long discussion about their battle experiences in Gaza.

Zamir said: “I do not intend that we will delve into the political meaning of the Operation Cast Lead. But a discussion is necessary because this was a military operation unprecedented in the history of the IDF, which defined new boundaries from the point of view of the ethical code of the army and the state of Israel.

This was a campaign which sowed destruction in the midst of the civilian residents [of Gaza]. It’s not clear whether it was possible to do it any other way. But at the end of the day we’ve completed the operation and the Qassam have not really been silenced. It is very possible that we will return to a future operation of even greater magnitude in the coming years, since the problem in Gaza is not simple and it’s not even clear that we can solve it.

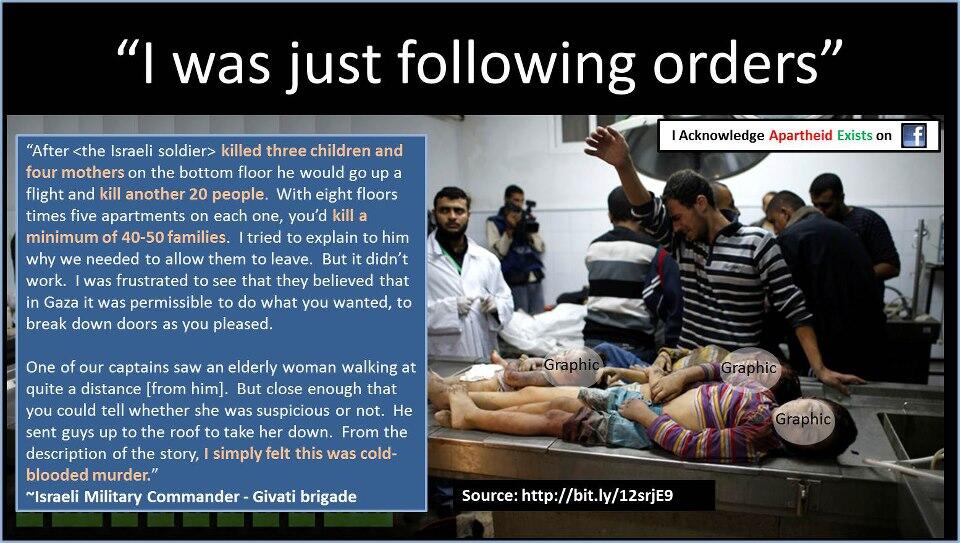

Aviv: I am a commander of a company in the Givati brigade. Towards the end of the operation there was a plan to enter a very densely populated sector in the middle of Gaza [City] itself. The leaders began to speak with us about the rules of opening fire within the city. Because as you know there was a great deal of fire and they killed many, many people so that we would not be injured or fired upon.

In the beginning, our aim was to get into a home. We were supposed to go in with an armored vehicle and break through the door, firing within and then…I call this simple murder. Basically, we were supposed to go floor by floor and any human being we came into contact with we shot at. This is something that at the beginning I said to myself: “does this make any sense?”

The higher-ups said it was permissible because anyone left in the vicinity or in the city was a terrorist, because they didn’t flee. I couldn’t understand it. On the one hand, they didn’t have anywhere to flee to, and on the other hand they didn’t flee and therefore it was their own fault [if they were killed].

I tried to influence, to the extent it was possible given my lowly assignment, to change this. Finally, they changed the orders and told us on entering the home to use loudspeakers and tell them: “let’s go, everyone get out, you have five minutes to exit the house, whoever doesn’t will be killed.”

I came to my troops and told them the orders had changed. We enter the house, tell them they have five minutes to flee, check everyone leaving to ensure they have no weapons and THEN go into the house and shoot anything that moved, to toss a hand grenade.

Then came a moment that unnerved me. One of my soldiers came to me and asked: “Why?” I replied: “What’s not clear? We don’t want to kill innocent civilians.” He said: “Why, anyone remaining there is a terrorist, that’s well-known.” His buddies then joined in: We needed to kill anyone we found there. Everyone in Gaza is a terrorist.

I tried to explain to him that not everyone we would encounter would be a terrorist. After he killed three children and four mothers on the bottom floor he would go up a flight and kill another 20 people. With eight floors times five apartments on each one, you’d kill a minimum of 40-50 families. I tried to explain to him why we needed to allow them to leave. But it didn’t work. I was frustrated to see that they believed that in Gaza it was permissible to do what you wanted, to break down doors as you pleased.

One of our captains saw an elderly woman walking at quite a distance [from him]. But close enough that you could tell whether she was suspicious or not. He sent guys up to the roof to take her down. From the description of the story, I simply felt this was cold-blooded murder.

by Richard Silverstein

Haaretz continues today with its coverage (in Hebrew) of testimony by IDF soldiers regarding their treatment of Gaza civilians during the recent war. Based on the information recounted it seems clear that a serious, in depth investigation of potential war crimes perpetrated by Israeli forces on orders from their superiors is necessary. The Israeli human rights group Yesh Din and Amnesty International have each called for such an inquiry.

Amnesty also brings word that 17 of the world’s most eminent jurists, many of whom conducted international war crimes tribunals (including Richard Goldstone), along with human rights activists (including Mary Robinson and Desmond Tutu) have called for a UN investigation of potential war crimes.

Their letter to Secretary General Ban Ki Moon can be read at the Amnesty site.

Amos Harel, the Haaretz reporter who first broke this story reports today that the IDF has launched a half-hearted investigation of the charges. But while going through the paces, it has also launched a frontal attack on Danny Zamir, the director of the Oranim College military preparatory program, who sponsored the meeting at which the soldiers revealed their stories.

Clearly, this is an IDF attempting to get out of dealing with the issues rather than addressing them forcefully. In the IDF, there is no such thing as bad behavior when it comes to mistreating Palestinians. The only time such activities are investigated and punished is when they’ve been videotaped for the world to see and the army cannot dispute what happened.

In this case, there is no documentary footage though there is the strong eyewitness testimony of soldiers on the ground. It remains to be seen whether this is of sufficient weight to rouse the military behemoth into action.

What follows is my translation of portions of the latest Haaretz story. Pay attention especially to the discussion of the religious zealotry of the Orthodox soldiers and how the rabbinate has turned the battle against the Palestinians into a holy war:

On Friday, Feburary , [Danny] Zamir brought together soldiers and captains, graduates of the military preparatory program, for a long discussion about their battle experiences in Gaza.

Zamir said: “I do not intend that we will delve into the political meaning of the Operation Cast Lead. But a discussion is necessary because this was a military operation unprecedented in the history of the IDF, which defined new boundaries from the point of view of the ethical code of the army and the state of Israel.

This was a campaign which sowed destruction in the midst of the civilian residents [of Gaza]. It’s not clear whether it was possible to do it any other way. But at the end of the day we’ve completed the operation and the Qassam have not really been silenced. It is very possible that we will return to a future operation of even greater magnitude in the coming years, since the problem in Gaza is not simple and it’s not even clear that we can solve it.

Aviv: I am a commander of a company in the Givati brigade. Towards the end of the operation there was a plan to enter a very densely populated sector in the middle of Gaza [City] itself. The leaders began to speak with us about the rules of opening fire within the city. Because as you know there was a great deal of fire and they killed many, many people so that we would not be injured or fired upon.

In the beginning, our aim was to get into a home. We were supposed to go in with an armored vehicle and break through the door, firing within and then…I call this simple murder. Basically, we were supposed to go floor by floor and any human being we came into contact with we shot at. This is something that at the beginning I said to myself: “does this make any sense?”

The higher-ups said it was permissible because anyone left in the vicinity or in the city was a terrorist, because they didn’t flee. I couldn’t understand it. On the one hand, they didn’t have anywhere to flee to, and on the other hand they didn’t flee and therefore it was their own fault [if they were killed].

I tried to influence, to the extent it was possible given my lowly assignment, to change this. Finally, they changed the orders and told us on entering the home to use loudspeakers and tell them: “let’s go, everyone get out, you have five minutes to exit the house, whoever doesn’t will be killed.”

I came to my troops and told them the orders had changed. We enter the house, tell them they have five minutes to flee, check everyone leaving to ensure they have no weapons and THEN go into the house and shoot anything that moved, to toss a hand grenade.

Then came a moment that unnerved me. One of my soldiers came to me and asked: “Why?” I replied: “What’s not clear? We don’t want to kill innocent civilians.” He said: “Why, anyone remaining there is a terrorist, that’s well-known.” His buddies then joined in: We needed to kill anyone we found there. Everyone in Gaza is a terrorist.

I tried to explain to him that not everyone we would encounter would be a terrorist. After he killed three children and four mothers on the bottom floor he would go up a flight and kill another 20 people. With eight floors times five apartments on each one, you’d kill a minimum of 40-50 families. I tried to explain to him why we needed to allow them to leave. But it didn’t work. I was frustrated to see that they believed that in Gaza it was permissible to do what you wanted, to break down doors as you pleased.

One of our captains saw an elderly woman walking at quite a distance [from him]. But close enough that you could tell whether she was suspicious or not. He sent guys up to the roof to take her down. From the description of the story, I simply felt this was cold-blooded murder.

Tzvi: Aviv’s description is correct. But it’s possible to understand from where this ideas comes. From their point of view she was not supposed to be there because there were announcements and warning shelling.

Logic tells you she shouldn’t be there. You describe this as cold blooded murder. But that’s not right. It’s well known that sent out people to spy on us and all that.

Gilad: Before we entered [Gaza], the regimental commander took pains to clarify to us that one of the lessons from the second Lebanon war was the way we entered [Gaza], with lots of firing. The intent was through the firepower to protect the lives of the soldiers. During the operation the IDF’s losses were light, but this resulted in many dead Palestinian civilians.

The entrance of the infantry was very aggressive. There were tanks with us. Every inch of ground was covered by firing.

Zamir: After incidents like this involving mistaken killings, were there any investigations? Do they check how they can prevent things from happening like this?

Ram: No one has yet come to investigate.

Moshe: The attitude is very simple. It’s not nice to say this, but if it doesn’t move anyone to act we don’t investigate. That’s what happens in battle.

Ram: The military rabbis sent us lots of material and in these articles the message was clear: we are the nation of Israel. We arrived by a miracle in Israel. God returned us to the Land [of Israel]. Now we must battle to remove the non-Jews who disturb us in our conquest of the Holy Land. That was the main message. And the sense of many of the soldiers in this operation was that it was a religious war. From my perspective as a commander, I tried to talk about politics and various strains within Palestinian society. That no everyone in Gaza was Hamas and not every resident wants to conquer us. I wanted to explain to them that this war was not about Kiddush Hashem (sanctifying the name of God), but about stopping Qassam fire.

Zamir: Among the pilots was there any sense of denial? It surprised me that on the first day of the campaign they took down Gaza’s traffic police. They took down 180 traffic police. This would arouse a question within me if I were a pilot.

Gideon: Let’s divide this into two. First, they are armed and second they are Hamas. On a good day, they take Fatah members and throw them off roofs.

From the moment you start your aircraft to the moment you turn it off, every thought is on the assignment you have to execute. If you allow yourself to doubt, you are likely to make a much worse mistake and knock down a school with 40 children inside. The price of such an error is very, very high.

Question from the audience: Were there any among the pilots who didn’t press the button or thought twice?

With the weapons I used, my ability to arrive at a decision that contradicts what they’ve told me up to that point is non-existent. I send off my missile at such a distance that I can see all of Gaza. I also see Haifa. From a great distance.

Logic tells you she shouldn’t be there. You describe this as cold blooded murder. But that’s not right. It’s well known that sent out people to spy on us and all that.

Gilad: Before we entered [Gaza], the regimental commander took pains to clarify to us that one of the lessons from the second Lebanon war was the way we entered [Gaza], with lots of firing. The intent was through the firepower to protect the lives of the soldiers. During the operation the IDF’s losses were light, but this resulted in many dead Palestinian civilians.

The entrance of the infantry was very aggressive. There were tanks with us. Every inch of ground was covered by firing.

Zamir: After incidents like this involving mistaken killings, were there any investigations? Do they check how they can prevent things from happening like this?

Ram: No one has yet come to investigate.

Moshe: The attitude is very simple. It’s not nice to say this, but if it doesn’t move anyone to act we don’t investigate. That’s what happens in battle.

Ram: The military rabbis sent us lots of material and in these articles the message was clear: we are the nation of Israel. We arrived by a miracle in Israel. God returned us to the Land [of Israel]. Now we must battle to remove the non-Jews who disturb us in our conquest of the Holy Land. That was the main message. And the sense of many of the soldiers in this operation was that it was a religious war. From my perspective as a commander, I tried to talk about politics and various strains within Palestinian society. That no everyone in Gaza was Hamas and not every resident wants to conquer us. I wanted to explain to them that this war was not about Kiddush Hashem (sanctifying the name of God), but about stopping Qassam fire.

Zamir: Among the pilots was there any sense of denial? It surprised me that on the first day of the campaign they took down Gaza’s traffic police. They took down 180 traffic police. This would arouse a question within me if I were a pilot.

Gideon: Let’s divide this into two. First, they are armed and second they are Hamas. On a good day, they take Fatah members and throw them off roofs.

From the moment you start your aircraft to the moment you turn it off, every thought is on the assignment you have to execute. If you allow yourself to doubt, you are likely to make a much worse mistake and knock down a school with 40 children inside. The price of such an error is very, very high.

Question from the audience: Were there any among the pilots who didn’t press the button or thought twice?

With the weapons I used, my ability to arrive at a decision that contradicts what they’ve told me up to that point is non-existent. I send off my missile at such a distance that I can see all of Gaza. I also see Haifa. From a great distance.

16 mar 2009

Ensuring maximum casualties in Gaza

Darts released from a flechette bomb.

“We were still young and in love. We had all of our dreams,” Muhammad Abu Jerrad said, holding a photo of his wife by the sea. Wafa Abu Jerrad was one of at least six killed by three flechette bombs fired by Israeli tanks in the Ezbet Beit Hanoun area, northern Gaza, on 5 January.

The dart bomb attacks came the morning after invading Israeli soldiers killed 35-year-old paramedic Arafa Abd al-Dayem. Along with another medic and ambulance driver, Abd al-Dayem was targeted by the lethal darts just after 10:10am on 4 January while trying to aide civilians already attacked by Israeli forces in northern Gaza’s Beit Lahia area. Within two hours of being shredded by multiple razor-sharp darts, Arafa Abd al-Dayem died as a result of slashes to his lungs, limbs and internal organs.

Khalid Abu Saada, the driver of the ambulance, testified to the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights: “I was told that there were injured people near the western roundabout in Beit Lahiya town. When we arrived, we saw a person who had been critically injured. The two paramedics climbed out of the ambulance to evacuate him into the ambulance. I drove approximately 10 meters ahead in order to evacuate another injured person. Then, an [Israeli] tank fired a shell at us. The shell directly hit the ambulance and 10 civilians, including the two paramedics, were injured.”

From his al-Shifa hospital bed the day after the attack, 21-year-old volunteer medic Alaa Sarhan, lacerated legs bandaged, confirmed the account. More than two months later, he remains wheelchair-bound, lacerated muscles and ligaments still too damaged for walking.

In the same post-attack hospital room as Sarhan was Thaer Hammad, one of the injured civilians whom medics had come to the region to retrieve. In the initial shelling that day, Hammad lost his foot when Israeli tanks fired at, according to Hammad, a region filled with terrified civilians fleeing Israeli bombing. His friend Ali was shot in the head while trying to evacuate Hammad. The medics then arrived. Abd al-Dayem and Sarhan had loaded Hammad into the ambulance and were going to retrieve Ali’s body when the flechette shell was fired at the medics and fleeing civilians. Ali was decapitated, and Abd al-Dayem received the injuries which would claim his life within hours.

Dr. Bakkar Abu Safia, head of the emergency department at al-Shifa hospital, treated Abd al-Dayem at Awda Hospital in Beit Lahiya.

“Arafa had received a direct hit on his chest, which was torn open, and had many small puncture wounds on his right and left arms. He had massive internal bleeding in his abdomen from the injury to his liver, and had blood in his lung. After we had closed his wounds and were transferring him to [the intensive care unit], he arrested. He had irreversible shock,” Dr. Bakkar said.

“We were still young and in love. We had all of our dreams,” Muhammad Abu Jerrad said, holding a photo of his wife by the sea. Wafa Abu Jerrad was one of at least six killed by three flechette bombs fired by Israeli tanks in the Ezbet Beit Hanoun area, northern Gaza, on 5 January.

The dart bomb attacks came the morning after invading Israeli soldiers killed 35-year-old paramedic Arafa Abd al-Dayem. Along with another medic and ambulance driver, Abd al-Dayem was targeted by the lethal darts just after 10:10am on 4 January while trying to aide civilians already attacked by Israeli forces in northern Gaza’s Beit Lahia area. Within two hours of being shredded by multiple razor-sharp darts, Arafa Abd al-Dayem died as a result of slashes to his lungs, limbs and internal organs.

Khalid Abu Saada, the driver of the ambulance, testified to the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights: “I was told that there were injured people near the western roundabout in Beit Lahiya town. When we arrived, we saw a person who had been critically injured. The two paramedics climbed out of the ambulance to evacuate him into the ambulance. I drove approximately 10 meters ahead in order to evacuate another injured person. Then, an [Israeli] tank fired a shell at us. The shell directly hit the ambulance and 10 civilians, including the two paramedics, were injured.”

From his al-Shifa hospital bed the day after the attack, 21-year-old volunteer medic Alaa Sarhan, lacerated legs bandaged, confirmed the account. More than two months later, he remains wheelchair-bound, lacerated muscles and ligaments still too damaged for walking.

In the same post-attack hospital room as Sarhan was Thaer Hammad, one of the injured civilians whom medics had come to the region to retrieve. In the initial shelling that day, Hammad lost his foot when Israeli tanks fired at, according to Hammad, a region filled with terrified civilians fleeing Israeli bombing. His friend Ali was shot in the head while trying to evacuate Hammad. The medics then arrived. Abd al-Dayem and Sarhan had loaded Hammad into the ambulance and were going to retrieve Ali’s body when the flechette shell was fired at the medics and fleeing civilians. Ali was decapitated, and Abd al-Dayem received the injuries which would claim his life within hours.

Dr. Bakkar Abu Safia, head of the emergency department at al-Shifa hospital, treated Abd al-Dayem at Awda Hospital in Beit Lahiya.

“Arafa had received a direct hit on his chest, which was torn open, and had many small puncture wounds on his right and left arms. He had massive internal bleeding in his abdomen from the injury to his liver, and had blood in his lung. After we had closed his wounds and were transferring him to [the intensive care unit], he arrested. He had irreversible shock,” Dr. Bakkar said.

At around 9:30am, they were eating breakfast in a sunny patch outside the front door of their home in what Muhammad described as a “calm” period. “Nothing was happening, not then, not half an hour earlier. It was calm. We were sitting outside because it felt safe.”

“We heard explosions, coming from up the street near the Abd al-Dayem house. We knew of Arafa’s death the day before,” Muhammad Abu Jerrad explained, saying the family moved to the side of the house to see what was happening.

“We saw bodies on the ground everywhere outside the Abd al-Dayem mourning tents. Wafa panicked and told us to go back inside, so we ran to the front of the house. We were all very worried.”

Abu Jerrad’s father Khalil and some of the family had made it inside the house, and Abu Jerrad himself was stepping in the doorway, two-year-old son Khalil in his arms, Wafa to his left, when they were struck by the darts of a new shelling.

The dart bomb exploded in the air, Wafa dropped to ground, struck by flechettes into the head, chest and back. She was killed instantly.

“I was struck at the same time, in my right arm and in my back,” Abu Jerrad recalled. “I fell over with my wife, passing out. I came to shortly after and saw my wife covered in blood. I picked her up and carried her to the car, running. Then I passed out again from the pain.”

Although Abu Jerrad’s father Khalil had been inside the doorway, he too was hit by the darts. Abu Jerrad’s son Khalil was hit by darts in his right foot and in one finger. One of the flechettes that struck Abu Jerrad remains deeply embedded near his spinal cord. Doctors fear removing the dart would injure a nerve and leave Abu Jerrad paralyzed.

According to Dr. Bakkar, in Gaza it won’t be possible for Abu Jerrad to get the surgery he needs. “We don’t have qualified specialists to do such intricate surgery in Gaza. He’d need surgery outside.” With more than 280 patients dead after being prevented by Israel, which controls Gaza’s borders, from reaching medical treatment outside of Gaza, Abu Jerrad holds no prospect of being granted permission by Israeli authorities to leave Gaza for surgery.

Although he is in considerable pain due to the sharp dart still lodged in his back, Abu Jerrad said the pain of his injury is minor compared to the loss of his wife.

“‘Where’s mommy? Where’s mommy?’” Abu Jerrad said two-year-old Khalil asks all the time. “Mommy has been hurt,” he tells him, kissing a photo of his wife and making the sound of an explosion, knowing that there is no way of softening the truth for his son.

“We’re totally innocent. We have nothing to do with rockets. We were just living in the house.”

The house still bears the evidence of the dart bomb: numerous darts still firmly entrenched in the concrete wall where the darts flew. Some of the darts still have fins visibly peeking out of concrete, others seem to be but nails poking out from the wall.

The Guardian (UK) newspaper published a graphic illustrating how upon a timed explosion in the air, flechette darts are designed to spread out conically, covering a vast area which Amnesty International cites as 300 meters wide and 100 meters long, inflicting the maximum number of injuries possible. In the case of a densely-populated region like the Gaza Strip, the number of potentially-injured is deathly high. The same graphic shows how the head of the dart is designed to break away. Having penetrated inside a person, this breakage inflicts a second wound per single dart entry, multiplying the amount of internal damage done by the razor-like darts, which Amnesty International said number between 5,000 and 8,000 per shell.

Dr. Bassam al-Masari, a surgeon at Beit Lahiya’s Kamal Adwan hospital, reiterated that flechettes cause more injuries than other bombs precisely because they spread in a larger area. And while the darts appear innocuously small, their velocity and design enable them to bore through cement and bones and “cut everything internal,” said al-Masari. Accordingly, the prime cause of death is severe internal bleeding from slashed organs, particularly the heart, liver and brain. “Brain injuries are the most fatal,” said al-Masari.

A few minutes up the road from the Abu Jerrad home, 57-year-old Jamal Abd al-Dayem and his wife, 50-year-old Sabah, grieve the deaths of their two sons, victims of the indiscriminate flechettes.

“Every time I think of them, every time I sit by their grave, I feel like I’m going to crumble. I was so happy with them,” Sabah Abd al-Dayem said.

“We heard explosions, coming from up the street near the Abd al-Dayem house. We knew of Arafa’s death the day before,” Muhammad Abu Jerrad explained, saying the family moved to the side of the house to see what was happening.

“We saw bodies on the ground everywhere outside the Abd al-Dayem mourning tents. Wafa panicked and told us to go back inside, so we ran to the front of the house. We were all very worried.”

Abu Jerrad’s father Khalil and some of the family had made it inside the house, and Abu Jerrad himself was stepping in the doorway, two-year-old son Khalil in his arms, Wafa to his left, when they were struck by the darts of a new shelling.

The dart bomb exploded in the air, Wafa dropped to ground, struck by flechettes into the head, chest and back. She was killed instantly.

“I was struck at the same time, in my right arm and in my back,” Abu Jerrad recalled. “I fell over with my wife, passing out. I came to shortly after and saw my wife covered in blood. I picked her up and carried her to the car, running. Then I passed out again from the pain.”

Although Abu Jerrad’s father Khalil had been inside the doorway, he too was hit by the darts. Abu Jerrad’s son Khalil was hit by darts in his right foot and in one finger. One of the flechettes that struck Abu Jerrad remains deeply embedded near his spinal cord. Doctors fear removing the dart would injure a nerve and leave Abu Jerrad paralyzed.

According to Dr. Bakkar, in Gaza it won’t be possible for Abu Jerrad to get the surgery he needs. “We don’t have qualified specialists to do such intricate surgery in Gaza. He’d need surgery outside.” With more than 280 patients dead after being prevented by Israel, which controls Gaza’s borders, from reaching medical treatment outside of Gaza, Abu Jerrad holds no prospect of being granted permission by Israeli authorities to leave Gaza for surgery.

Although he is in considerable pain due to the sharp dart still lodged in his back, Abu Jerrad said the pain of his injury is minor compared to the loss of his wife.

“‘Where’s mommy? Where’s mommy?’” Abu Jerrad said two-year-old Khalil asks all the time. “Mommy has been hurt,” he tells him, kissing a photo of his wife and making the sound of an explosion, knowing that there is no way of softening the truth for his son.

“We’re totally innocent. We have nothing to do with rockets. We were just living in the house.”

The house still bears the evidence of the dart bomb: numerous darts still firmly entrenched in the concrete wall where the darts flew. Some of the darts still have fins visibly peeking out of concrete, others seem to be but nails poking out from the wall.

The Guardian (UK) newspaper published a graphic illustrating how upon a timed explosion in the air, flechette darts are designed to spread out conically, covering a vast area which Amnesty International cites as 300 meters wide and 100 meters long, inflicting the maximum number of injuries possible. In the case of a densely-populated region like the Gaza Strip, the number of potentially-injured is deathly high. The same graphic shows how the head of the dart is designed to break away. Having penetrated inside a person, this breakage inflicts a second wound per single dart entry, multiplying the amount of internal damage done by the razor-like darts, which Amnesty International said number between 5,000 and 8,000 per shell.

Dr. Bassam al-Masari, a surgeon at Beit Lahiya’s Kamal Adwan hospital, reiterated that flechettes cause more injuries than other bombs precisely because they spread in a larger area. And while the darts appear innocuously small, their velocity and design enable them to bore through cement and bones and “cut everything internal,” said al-Masari. Accordingly, the prime cause of death is severe internal bleeding from slashed organs, particularly the heart, liver and brain. “Brain injuries are the most fatal,” said al-Masari.

A few minutes up the road from the Abu Jerrad home, 57-year-old Jamal Abd al-Dayem and his wife, 50-year-old Sabah, grieve the deaths of their two sons, victims of the indiscriminate flechettes.

“Every time I think of them, every time I sit by their grave, I feel like I’m going to crumble. I was so happy with them,” Sabah Abd al-Dayem said.

|

Jamal Abd al-Dayem sitting with his wife, Sabah, holds a dart from a flechette bomb

Jamal Abd al-Dayem explained the events. “After my cousin Arafa was martyred on 4 January, we immediately opened mourning houses, with separate areas for men and women. The next day, at 9:30am the Israelis struck the mourning area where the men were. It was clearly a mourning house, on the road, open and visible. Immediately after the first strike, the Israelis hit the women’s mourning area.” Two strikes within 1.5 minutes, he reported. |

“When Arafa was martyred, my sons cried so much their eyes were red and swollen with grief. The next day they were martyred,” the father said, shaking his head in disbelief.

“Just like that, I lost two sons. One of them was newly married, his wife eight months pregnant.”

Twenty-nine-year-old Said Abd al-Dayem died after one day in the hospital, succumbing to the fatal injuries of darts in his head. His unmarried brother, Nafez Abd al-Dayem, 23, was also struck in head by the darts and died immediately.

The surviving son, 25-year-old Nahez Abd al-Dayem, was hit by two darts in his abdomen, one in his chest, and another in his leg.

“I went to the mourning house to pay respects to my cousin, Arafa. When we arrived at the men’s mourning house, there was a sudden explosion and I felt pain in my chest. Very quickly after, there was a second strike. This second attack was more serious as people had rushed to the area to help the wounded. I looked up from the second shelling and saw that my cousins Arafat and Islam had been hit. They were lying on the ground, wounded.”

Sixteen-year-old Islam Abd al-Dayem was struck in the neck and died slowly, in great agony, after three days in the hospital. Fifteen-year-old Arafat Abd al-Dayem died instantly.

When Nahez Abd al-Dayem regained consciousness in hospital, he learned of his two dead brothers and two dead cousins. The dart that lodged in his leg was surgically removed, but three darts remain in his chest and abdomen and will stay there, although Abd al-Dayem says they bother him. “When I move at night, I feel a lot of pain,” he said. But an operation to search for them is too dangerous and could cause greater injury.

The dart shelling on the Abd al-Dayem and Abu Jerrad houses killed six and injured at least 25, including a 20-year-old nephew paralyzed from the neck down after darts severed his spinal cord. Darts which spread as far as 200 meters from the scene are still embedded in walls of houses.

Atalla Muhammad Abu Jerrad, 44 years old, explained, “I was near the mourning house, on my way to the market. I saw everything. My brother Otalla, 37, was in the area. He was injured by a nail that drilled through his shoulder, and lodged in his neck. He had to have an operation to remove it.”

Sabah Abd al-Dayem said she finally understands the expression “burning with pain.” “Every minute, every hour I think of them. My son didn’t have time to enjoy married life. I wish I had died with them.”

“In five or six months, you’ll see the effects on her,” Jamal Abd al-Dayem said of his wife. “She isn’t eating, drinking, or sleeping. I’ve hidden all the photos of our sons and closed off [their] room.” The photos he’d mentioned had been laid out on display. Pictures of their sons at different ages and stages of life. A photo of Said graduating from university.

Jamal Abd al-Dayem, tall, with a salt and pepper beard and hair, and deep smile wrinkles, is equally affected.

“Our lives have stopped. We don’t go to any joyful places, don’t do anything fun. We just mourn our sons and their lost lives. Our children are precious to us. We raised them and now they’re gone. Said’s wife has gone back to her parents’ house. She can’t bear it here. Now half of our household is gone. What have we done? What fault is it of ours? There was no need to target the mourning houses.”

Their youngest daughter, 14-year-old Eyat, used to be at the top of her class, her parents said. Now, they said, she suffers at school, crying in class, thinking of two dead brothers. “She can’t concentrate,” Jamal Abd al-Dayem said. “Her brain is closed.”

Aside from the memories of the day his sons were martyred, Jamal Abd al-Dayem has tangible reminders of their deaths. From a pink paper bag decorated with teddy bears and hearts he brought out a single flechette, one of the many he’s kept from the thousands unleashed on his family and relatives.

Yet it is out of more than sentimentality that Abd al-Dayem has kept the darts. He wants justice.

“Our sons’ lives are not cheap, can’t just let them go like that. If they die a natural death, that’s one thing. But like this? Where are our rights? We want a trial. What right [is there] to bomb a mourning house?”

Amnesty International and many other recognized rights organizations have long been critical of Israel’s use of flechette bombs in the densely-populated Gaza Strip. The group Physicians for Human Rights-Israel says Israel’s use of flechette bombs is in contravention to the Geneva conventions. B’Tselem, an Israeli rights group, reported that at least 17 Palestinians were killed by dart bombs from 2000 through the 18 April 2008 killing of a Palestinian cameraman and three other civilians, including two minors, by a flechette bomb in Gaza.

The attack raised renewed alarm among international rights groups about Israel’s use of the indiscriminate and deadly dart bombs. Joe Stork, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), said that the “use of flechette shells, with a wide ‘kill radius,’ increases the chance of indiscriminately hitting civilians,” adding that Israel “should stop its use of the weapon in Gaza, which is one of the most densely populated areas on Earth.”

Years before, HRW’s Hanny Megally had noted Israel’s usage of the darts in Gaza only, versus in the occupied West Bank where the illegal Israeli settlements and Israeli military bases are in many areas intertwined with Palestinian residential areas. Whereas using dart bombs in a Gaza district only puts Palestinians in neighboring areas at risk, the use of such flechettes would put many of the nearly 500,000 illegal Israeli settlers at risk of injury.

Despite Israeli officials’ frequent justifications that the use of flechettes is permitted under international law, there are guidelines to this usage which the Israeli military continues to willfully ignore.

It is precisely the use of flechettes in densely populated areas which contravene the internationally-accepted principles of war: the inability of the dart bombs to distinguish between military targets and civilians; and the lack of precaution at avoiding civilian injury or death.

The two-inch-long scar on Rami al-Lohoh’s right shoulder is his reminder of the painful dart which had penetrated deeply beneath the flesh of his shoulder area. The 11-year-old was too shy to speak of his injury, but obligingly pulled his shirt aside to reveal the scar. X-rays taken after the dart had embedded in al-Lohoh reveal the depth of its penetration.

“The doctors were afraid of this type of injury, so they hesitated before doing the operation to remove the dart,” Rami’s father Darwish al-Lohoh explained. After a 2.5 hour operation, the potentially deadly dart was removed.

“Just like that, I lost two sons. One of them was newly married, his wife eight months pregnant.”

Twenty-nine-year-old Said Abd al-Dayem died after one day in the hospital, succumbing to the fatal injuries of darts in his head. His unmarried brother, Nafez Abd al-Dayem, 23, was also struck in head by the darts and died immediately.

The surviving son, 25-year-old Nahez Abd al-Dayem, was hit by two darts in his abdomen, one in his chest, and another in his leg.

“I went to the mourning house to pay respects to my cousin, Arafa. When we arrived at the men’s mourning house, there was a sudden explosion and I felt pain in my chest. Very quickly after, there was a second strike. This second attack was more serious as people had rushed to the area to help the wounded. I looked up from the second shelling and saw that my cousins Arafat and Islam had been hit. They were lying on the ground, wounded.”

Sixteen-year-old Islam Abd al-Dayem was struck in the neck and died slowly, in great agony, after three days in the hospital. Fifteen-year-old Arafat Abd al-Dayem died instantly.

When Nahez Abd al-Dayem regained consciousness in hospital, he learned of his two dead brothers and two dead cousins. The dart that lodged in his leg was surgically removed, but three darts remain in his chest and abdomen and will stay there, although Abd al-Dayem says they bother him. “When I move at night, I feel a lot of pain,” he said. But an operation to search for them is too dangerous and could cause greater injury.

The dart shelling on the Abd al-Dayem and Abu Jerrad houses killed six and injured at least 25, including a 20-year-old nephew paralyzed from the neck down after darts severed his spinal cord. Darts which spread as far as 200 meters from the scene are still embedded in walls of houses.

Atalla Muhammad Abu Jerrad, 44 years old, explained, “I was near the mourning house, on my way to the market. I saw everything. My brother Otalla, 37, was in the area. He was injured by a nail that drilled through his shoulder, and lodged in his neck. He had to have an operation to remove it.”

Sabah Abd al-Dayem said she finally understands the expression “burning with pain.” “Every minute, every hour I think of them. My son didn’t have time to enjoy married life. I wish I had died with them.”

“In five or six months, you’ll see the effects on her,” Jamal Abd al-Dayem said of his wife. “She isn’t eating, drinking, or sleeping. I’ve hidden all the photos of our sons and closed off [their] room.” The photos he’d mentioned had been laid out on display. Pictures of their sons at different ages and stages of life. A photo of Said graduating from university.

Jamal Abd al-Dayem, tall, with a salt and pepper beard and hair, and deep smile wrinkles, is equally affected.

“Our lives have stopped. We don’t go to any joyful places, don’t do anything fun. We just mourn our sons and their lost lives. Our children are precious to us. We raised them and now they’re gone. Said’s wife has gone back to her parents’ house. She can’t bear it here. Now half of our household is gone. What have we done? What fault is it of ours? There was no need to target the mourning houses.”

Their youngest daughter, 14-year-old Eyat, used to be at the top of her class, her parents said. Now, they said, she suffers at school, crying in class, thinking of two dead brothers. “She can’t concentrate,” Jamal Abd al-Dayem said. “Her brain is closed.”

Aside from the memories of the day his sons were martyred, Jamal Abd al-Dayem has tangible reminders of their deaths. From a pink paper bag decorated with teddy bears and hearts he brought out a single flechette, one of the many he’s kept from the thousands unleashed on his family and relatives.

Yet it is out of more than sentimentality that Abd al-Dayem has kept the darts. He wants justice.

“Our sons’ lives are not cheap, can’t just let them go like that. If they die a natural death, that’s one thing. But like this? Where are our rights? We want a trial. What right [is there] to bomb a mourning house?”

Amnesty International and many other recognized rights organizations have long been critical of Israel’s use of flechette bombs in the densely-populated Gaza Strip. The group Physicians for Human Rights-Israel says Israel’s use of flechette bombs is in contravention to the Geneva conventions. B’Tselem, an Israeli rights group, reported that at least 17 Palestinians were killed by dart bombs from 2000 through the 18 April 2008 killing of a Palestinian cameraman and three other civilians, including two minors, by a flechette bomb in Gaza.

The attack raised renewed alarm among international rights groups about Israel’s use of the indiscriminate and deadly dart bombs. Joe Stork, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), said that the “use of flechette shells, with a wide ‘kill radius,’ increases the chance of indiscriminately hitting civilians,” adding that Israel “should stop its use of the weapon in Gaza, which is one of the most densely populated areas on Earth.”

Years before, HRW’s Hanny Megally had noted Israel’s usage of the darts in Gaza only, versus in the occupied West Bank where the illegal Israeli settlements and Israeli military bases are in many areas intertwined with Palestinian residential areas. Whereas using dart bombs in a Gaza district only puts Palestinians in neighboring areas at risk, the use of such flechettes would put many of the nearly 500,000 illegal Israeli settlers at risk of injury.

Despite Israeli officials’ frequent justifications that the use of flechettes is permitted under international law, there are guidelines to this usage which the Israeli military continues to willfully ignore.

It is precisely the use of flechettes in densely populated areas which contravene the internationally-accepted principles of war: the inability of the dart bombs to distinguish between military targets and civilians; and the lack of precaution at avoiding civilian injury or death.

The two-inch-long scar on Rami al-Lohoh’s right shoulder is his reminder of the painful dart which had penetrated deeply beneath the flesh of his shoulder area. The 11-year-old was too shy to speak of his injury, but obligingly pulled his shirt aside to reveal the scar. X-rays taken after the dart had embedded in al-Lohoh reveal the depth of its penetration.

“The doctors were afraid of this type of injury, so they hesitated before doing the operation to remove the dart,” Rami’s father Darwish al-Lohoh explained. After a 2.5 hour operation, the potentially deadly dart was removed.

|

Rami al-Lohoh shows the scar on his shoulder and an X-ray of the dart lodged deep in Rami’s shoulder.

|

Hossam al-Lohoh, Rami’s 13-year-old brother, recalled in detail where the family was when he was hit by multiple flechette darts.

“We were walking near [our friend] Ayman’s home. The Israelis fired a missile. When the missile hit the road it exploded and all the pieces inside spread widely. It felt like someone had thrown many, many stones at me. We looked for somewhere safe to run to for shelter. We ran into a small street. I felt a huge pain in my head and legs then I passed out.” Hossam al-Lohoh, currently forced to limp, will need another operation six months later to repair the damaged nerves in his leg. The 10-member al-Lohoh family, including eight youths, had taken refuge in the home of Ayman Qader, half a kilometer away, but had returned briefly to check on their home in Nusseirat refugee camp, central Gaza, on 13 January. |

|

|

Israeli tanks, which were stationed at the former Netzarim settlement, unleashed the flechette bomb as the family walked down Salah al-Din, the main north-south road. It was just after 3pm and the family was approximately 20 meters from the Qader home when the Israeli tanks shelled the group of civilians.

“The street was filled with darts,” 25-year-old Amer al-Mesalha recalled. He was among the 13 persons injured by the darts, most of whom were attempting to take refuge in a UN school. Mesalha had darts surgically removed from his hand and leg but still has two remaining in his abdomen, the entry point his lower back near the spine. Like the other victims, Mesalha is forced to accept the darts’ presence in his stomach. He said he has to be careful not to jump or move the metal bits inside him. Mesalha believes the Israeli soldiers knew who they were targeting. “The Israelis could see the group of people; they aimed at us.” |